The

Mendele Review: Yiddish Literature and Language

(A Companion to MENDELE)

---------------------------------------------------------

Contents of Vol. 12.010 [Sequential No. 201]

Date: 11 May 2008

1) This issue of TMR (ed).

2) Anniversary

messages (continued) [See TMR 12.009]

Professor Lawrence A. Rosenwald

(Wellesley College, Wellesley, MA)

FRIDA (Grapa de) CIELAK

(Mexico City, Mexico)

Dr. Marcos Silber (Department

of Jewish History, University of Haifa)

Boris Sandler, Ed./ Itsik

Gottesman, Asst. Ed., Forverts

(New York)

The Yiddish Leyen-Krayz of

Buffalo, New York

3) Review: Miriam Hoffman's Shlisl – a New Yiddish Textbook (Heather

Valencia)

4) Review: Mirjam Gutschow's Inventory of Yiddish Publications From the

Netherlands (c. 1650-cc.1950)

5) Uriel Birnbaum's "Yosele in Kheyder" and "Yankev

Dinezon"

6) Dutch klezmer group play "Holland terkisher"

1)---------------------------------------------------

Date: 11 May 2008

From: ed.

Subject: This

issue of TMR

Re past issues: ***The opening speech by Nosn Birnboym at

Czernowitz in 1908 in Yiddish [see TMR 12.009] may be found in an English

translation at http://www.ibiblio.org:80/yiddish/Tshernovits/birnbaum-op.html.

From a member of the

Re this issue: ***A brief note on the editor's helpmate, Barbara,

and a few more congratulatory messages on the TMR's anniversary (see TMR 12.009).

***Uriel Birnbaum (13 November, 1894 in

2)----------------------------------------------------

Date: 11 May 2008

From: ed.

Subject: Anniversary messages (continued) [See TMR 12.009]

Barbara M. Prager:

A glaring omission in my mini-biographical sketch in the anniversary

issue TMR 12.009 was mention of my principal

helper and support in my work, namely my very modest wife, Barbara, who

preferred not being candidly praised and having her considerable achievements

enumerated. But to sketch the minimal, she played the viola in the Haifa

Symphony Orchestra for over thirty years, many of them as Principal Violist,

has a first degree in music from

Congratulatory Messages:

Professor Lawrence A. Rosenwald (

A very happy

birthday to you, O now eleven-year-old Mendele Review! I had the honor to

write an article for the very first Mendele Review; when I look back at that issue, and that

article, I'm both awed and delighted at how the Review has survived,

grown, flourished , even transcended itself-- an astonishing success, and all

honor to Leonard Prager for gently and irresistibly making it

happen.

Larry A.

Rosenwald

----------------------

FRIDA

(Grapa de) CIELAK (

200 hundert

numern un 11 yor vos Yidish hot zikh modernizirt a dank MENDELE ONLINE, a

vunderbarer kholem fun Noyekh Miller un fun ale zayne mithelfer un fraynd, a

dank zayn akshoneshkeyt un Leonard Prager’s, tzu bavayzn der velt az Yidish

lebt, un itst iz a gute gelegenheyt az ale mitglider fun MENDELE, vos

tseyln zikh shoyn in di toyznter, az mir zoln aykh vayter shtitsn un aykh ale

opgebn a yasher koyekh un a derkenung far di vunderbare arbet in di elf yor,

alevay vayter, mit vayterdike dergreykhungen un zol G__ aykh bentshn mit gezunt

un hatslokhe! Mit fil anerkenung un hartsike grusn,

Freydl

Cielak (Meksike)

----------------------

Dr. Marcos

Silber (Department of Jewish History)

Biz hundert un

tsvantsik! Lomir hobn nokh a sakh vertfule artiklen fun Mendele Review!

Dr. Marcos Silber

----------------------

Dr. Helen Beer (

Dear Leonard,

It was a fargenign to read your biography (short version) and to

see the photos and have them explained.

You have done much to assure Mendele's success and global impact and you are

still the person who has most seriously and comprehensively investigated der

gantser inyen of Yiddish in

Helen

----------------------

Forverts (

Der

"Forverts" bagrist Leonard Prager tsum 200stn numer funem Mendele

Review.

A yasher-koyekh far ayer vikhtiker kultur-arbet letoyves undzer yidish-velt!

Boris

Sandler, shef-redaktor; Itzik Gottesman, shtel-fartreter farn redaktor, Forverts

(New York)

----------------------

The Yiddish Leyen-Krayz of

The Yiddish Leyen-Krayz of

Sincerely,

Jack Freer, Itsik Goldenberg, Floyd Green, Amy Eglowstein, Velvel Fleischman,

Irving Massey, Harvey Rogers,

3)-----------------------------------------------------

Date: 11 May 2008

From: Heather Valencia

Subject: Review of Miriam Hoffman's Shlisl – A new Yiddish textbook

Miriam

Hoffman, Shlisl tsu yidish/Key to Yiddish. Lernbukh far onheyber.

(

Yiddish

teachers never stop searching for the perfect course-book. During the past

twenty-five years, various new publications have built on the pioneering work

of Yudl Mark and Uriel Weinreich: Mordkhe Schaechter's Yidish tsvey, Sheva Zucker's Yiddish. An Introduction to

the Language, Literature and Culture, Volumes 1 and 2, Marion Aptroot and

Holger Nath's course for German-speaking students Yiddische Sprache und

Kultur, David Goldberg's Yidish af Yidish, and Zuckerman and

Herbst's Learning Yiddish in Easy Stages are all widely used and each

has its strengths and weaknesses, depending on the type and nationality of

student and the particular learning situation. The latest work to join this pantheon is Shlisl tsu

Yidish/ Key to Yiddish by Miriam Hoffman of

The author,

who is well-known to many Mendele readers, has a long and distinguished career

in Yiddish. She is a native speaker whose parents came from

Professor

Rakhmiel Pelz, who was instrumental in bringing her to

There is

indeed much from which to “nash”. The book comprises 666 A4 pages. This format

with its large, clear print and generously spaced layout make it easy for

students to read, but the downside of this is that the book weighs in at almost

two and a half kilos, and is therefore very heavy and unwieldy for them to

carry around! It is divided into fourteen chapters, which vary in length from

12 pages to 37 pages. From the point of

view of subject matter, most of the later chapters have a specific unifying

theme: (such as chapter 9: “Der khurbm,” chapter 11: “folksmayses,” and chapter

14: “Fun der yidisher literatur”), while the earlier ones are a pot-pourri of

different short texts and activities.

The material

which Miriam Hoffmann introduces to the reader is truly impressive. The book is

packed with interesting and lively texts: proverbs, Yiddish sayings, folksongs,

folktales, poetry, depictions of the various Jewish holidays and traditional

Ashkenazic customs, satirical texts, and comic anecdotes. The texts are

wide-ranging and authentic: as well as lively dialogues written by the author

herself, there are letters from the famous bintl briv in the Forverts

from the early twentieth century,

material on Yiddish dialects, on the relationship between Yiddish and loshn

koydesh, on Zionism and

The texts

present the student with a wide range of style and register, and the language

Hoffman herself uses when addressing the reader and in the exercises and

activities is humorous, pithy and idiomatic. The activities for developing

conversational skills, and the exercises to practise grammar points are on the

whole well thought out (though see my reservations below) and form an excellent

resource for teachers. There is a good selection of cumulative rhymes and

dialogues for classroom use, which enable even the beginner to contribute and

feel involved.

Another

attractive feature is the wealth of illustration. The chapters are sprinkled with

little black and white drawings and cartoons, the majority, as the author tells

us, from the satirical journal Der groyser kundes, but some also by the

modern artist Tsirl Waletsky. The

illustrations do not necessarily bear any relation to the particular

content of the chapters, but they add to the varied picture of Jewish life during the twentieth century which the

book as a whole conveys, and provide excellent stimulus for discussion.

As with all

the other Yiddish course books with which I am familiar, Shlisl tsu yidish

begins by teaching the Yiddish alphabet, which is very clearly set out.

However, this introductory section does not stand alone: certain aspects are

not specifically explained: the vowels and dipthongs which are preceded by the shtumer

alef, the use of the melupm vov and khirek yud, or the

function of yud as vowel or consonant. Here and in the pronunciation and

meaning of the large numbers of words which are introduced at the very

beginning, fairly intensive input from the teacher would be necessary.

In the English

version of her introduction, the author notes: “Instead of the usual

glossary, the English translation

follows immediately after the Hebrew element words, as well as phrases and

idioms. Hopefully each student will acquire a Yiddish-English/English-Yiddish

Dictionary and use it whenever necessary.” In fact far more than just the

Hebrew element vocabulary and some phrases and idioms are glossed in this way

in the texts: in the songs and poems, a parallel fairly literal translation is

provided on the left of the page, which is quite satisfactory, whereas many of

the prose texts are peppered with English glosses in brackets. It certainly

enables the students to read more easily when they have the pronunciation of Hebrew-origin words

immediately after their occurrence, but the effectiveness of the strategy as a

whole could be questioned. On the one hand, the student has the satisfaction of

being able to go through a text without pausing to look up words (assuming the

glossed words are the only one he/she needs) but there are, to my mind, other

negative effects. . The translations are not always literal, and in a phrase

containing various components, including, for example, the past participle of a

previously unknown verb, the student may not be clear which component is which

or enabled to learn the new verb. The presence of these glosses within the text

could also be a disincentive for the lazier student to learn the words whose

meaning has been handed to him/her on a plate!

Conversely, they may be an irritation to the student who already knows

the words, whereas with a word list after the passage, the student need

only look up items with which he/she is unfamiliar. Furthermore, these

interspersed words and phrases interrupt the flow and structure of the Yiddish

sentence, which impedes reading fluency.

It could be argued that the more traditional method - an uninterrupted

passage of Yiddish followed by a vocabulary list - is more productive. The

example reproduced below may help readers to decide on the efficacy of

Hoffman's strategy.

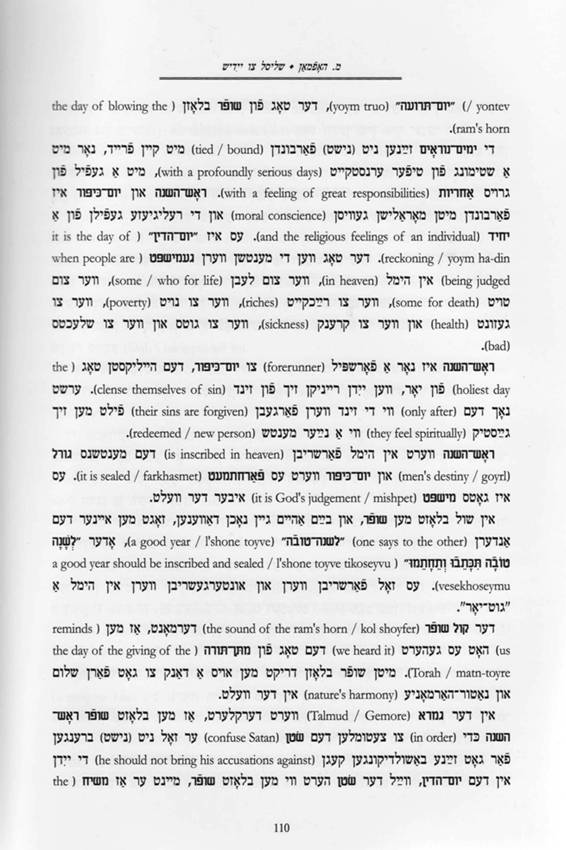

(click on image to enlarge)

The author

believes in teaching grammar with a light hand, and one can welcome the fact

that she has eschewed the long descriptive grammar sections in English which

feature in more traditional language courses. Instead, her grammar sections are

short and pithy, focusing on one point with a short explanation – usually in

Yiddish but with English translation of all or part of the explanation in order

to ensure understanding - followed by

examples and exercises to reinforce the point. There is no apparent pattern to

the occurrence of grammar sections within the chapters – which, as I have

already said, are of widely varying length.

They seem to appear at random, so that some chapters contain as many as

twelve new grammatical topics, while others are mainly made up of texts, with

very little or no grammatical input. All the main basic aspects are, however,

covered, and a particularly nice feature are frequent little sections

explaining pairs of elements like visn/kenen, rikhtik/gerekht, forn/geyn,

in/keyn and so on.

There are,

however, some unfortunate errors and inconsistencies in the teaching of the

grammatical points. Terminology is sometimes misleading or confusing: the

section on the present tense of the verb is entitled “Pronomen in der itstiker

tsayt (Declension of Personal Pronouns in the Present Tense)” and is followed,

not by the declension of pronouns, but by the conjugation of the verbs geyn,

kumen, shraybn, leyenen and farshteyn. (Although this section uses the

infinitive of the verb, the concept of the infinitive and the rules for the -n or -en endings are not dealt with

until chapter two, p.73.) There are unfortunate mistakes: under the heading of

“Sentences with an object” the sentences “zi iz a mentsh,” “Es iz an epl” are

given as examples. In the same section “Ikh shrayb a bukh” and “Du trinkst

kave” are given among the examples of plural sentences. At a more advanced

level, the conditional tense is

introduced in chapter 11 (p.535) under the heading “Der bading-hilfsverb

“volt”, which is explained as follows: “Der bading-verb “volt” vert genutst in

beyde teylzatsn. Der bading-verb muz genutst vern mit der fargangener tsayt. [sic]. (Italics in original. This is translated as

“past participle” in the English version of this explanation). However ALL the

example sentences she gives follow the pattern “Ven er veyst vos er tut,

volt er efsher fardint”, as do all the conditional questions in the exercise

for classroom discussion on p.537, e.g: “Ven a fish ken redn, vos volt

er gezogt?”. In the whole section there is not one example of “volt” being used

in both sentence-halves.

The order of

teaching various grammatical items can be confusing: apart from the above

example of the infinitives, we see for example on p. 78 that the student is

expected to do an exercise involving the verb “ton”, but the conjugation of

this irregular verb is not taught until p. 80. The teaching of the past tense is

particularly confusing. In chapter one, having only just dealt with the present

tense, and the verbs zayn and hobn, the author has a section (p.48) on intransitive verbs,

headed “Yiddish has some twenty intransitive verbs that have no object.

Intransitive verbs use the verb to be, zayn, in the Past Tense.” There follows

a list of these verbs in the past tense – without any prior discussion of the

formation of the past tense with zayn/hobn, the form of the past participle, or

the concept of transitive and intransitive verbs. Immediately after this, there

is an exercise to change present tense of “zayn” verbs to past tense (in which

the first sentence is “Du farshteyst a sakh”!), and an exercise with a

mixture of both “zayn” and “hobn” verbs,

though the latter category has not even been mentioned. The past tense is not

formally taught until chapter four, p.116. Here it is stated that “Only a

limited amount of verbs use “zayn” in the past tense” with the verb “zayn” as

the example, and no reference back to the list of intransitive verbs in

chapter one.

These and

other inconsistencies in the grammatical sections are potentially

bewildering for new students and would,

I feel, need to be remedied for a later edition (as would the irritating

profusion of misprints in the English text). However, the weaknesses which I

have mentioned undoubtedly stem largely from the fact that the book is a

collection of the teaching materials which Miriam Hoffman has developed and

successfully used with her students throughout the years, rather than a course

conceived ab initio and systematically planned. In the classroom

situation, the teacher using these materials would be able to smooth out any

misunderstandings and amplify explanations where necessary. Thus Shlisl tsu

yidish should perhaps not be considered as a tool for self-study. Its great

strength is primarily as a source of invigorating materials for classroom

teaching, and it will certainly stimulate lively participation and the

students' understanding of and engagement with the authentic Yiddish language

and culture. It is a valuable addition to the stock of modern Yiddish

textbooks.

4) -------------------------------------

Date: 11 May 2008

From: ed.

Subject: Review of Mirjam Gutschow's Inventory

of Yiddish Publications From the

[A Hebrew version of

this review will appear in Volume 11 of Khulyot]

Mirjam Gutschow's Inventory

of Yiddish Publications from the Netherlands c.1650-c.1950 (Leiden/Boston:

Brill, 2007) is an exemplary production that no one interested in the

socio-cultural history of Dutch Jewry, the development of Jewish printing, the

history of Yiddish and other related subject areas can afford not to know, use

and treasure. We also need to remember, as the author explains from the very

outset in her succinct "Introduction", that it is a reference work

wholly constructed from secondary as distinct from original sources. Seeing is

not necessarily believing, but for the discipline of bibliography actual

examination of texts is a prime desideratum.

Gutschow with full

candor writes: "As a first step towards a comprehensive bibliography of

Yiddish texts printed in the Netherlands, this inventory is based on

information extracted from secondary literature and is therefore subject to the

limitations of these sources..."(1) Her

principal source, she tells us, is Vinograd's Thesaurus of the Hebrew Book "despite

its limitations."(2) In dealing with her

multiple sources she has had to contend with "widespread differences in

orthography, pagination, format, printers, and even the year of

printing."(3) Regrettably, she was unable

to consult all catalogues of libraries having Yiddish books, and especially the

magnificent holdings of Yivo and the New York Public Library. She regrets, too,

omission of most of the pseudo-Amsterdam printings and of calendars and rightly

recognizes the need for studying these subjects further. However, viewing her

project as a whole, one must conclude that its omissions and shortcomings are

dwarfed by what it does achieve. (4)

Ashkenazim began

arriving in the

Items in Inventory are given according to chronology and titles are in Hebrew characters. The usefulness of the work is augmented by a liberal supply of indexes: List of Libraries and Collections, Bibliography (very comprehensive) (6), Indexes of Titles, Authors (includes translators), Printers and Genres. Beneath each item, Gutschow has placed a genre identification. Beside Judaic categories such as "Bible", "Kabbalah", "Liturgy", "Musar", we have the more frequent secular ones such as "Geography", "History", "Humor", "Narrative Prose", "Popular Medicine". YidNet 176 [the suggested system of citation--LP] is an adaptation of Boccacio's Decameron! The book's last section is a skillfully photographed collection of forty plates of title pages (or representative ones) of items listed in the Inventory. The plates give the item number and the items give the plate number. (Plates No. 1 and No. 16 are given here below. Click on images to enlarge)

The state

fought hard against Yiddish and for Dutch; most Jews shifted to Dutch (not

always free of Yiddish elements) by the end of the nineteenth century. A score

or so of Jewish periodicals in Dutch were published in the nineteenth century

(e.g. in

Endnotes

1. Inventory... Page 3.

2

Vinograd, Otsar …..

3. Inventory...Page

3.

4. I would

have been happier if a simple Key to Abbreviations had straightaway

informed me what C, F, R, and Z stand for. (They are catalogues by authors

whose names start with these initials.) And small f. ('leaf") < Latin folium

will be foreign to many users -- IDC and others use leaves.

5. Shlomo Berger's important essay "An

Invitation to Buy and Read; Paratexts of Yiddish Books in

6. A title list of "Yiddish Publications

from the

7. See the Dutch items at: http://www.nypl.org/research/chss/jws/documents/microfilmsotherlanguages.pdf

8. See The Mendele Review 05.001

[4d] (31 January 2001) and http://www.xs4all.nl/~fredbor/0.5/UK/home_uk.html

5)-----------------------------------------------------

Date: 11 May 2008

From: ed.

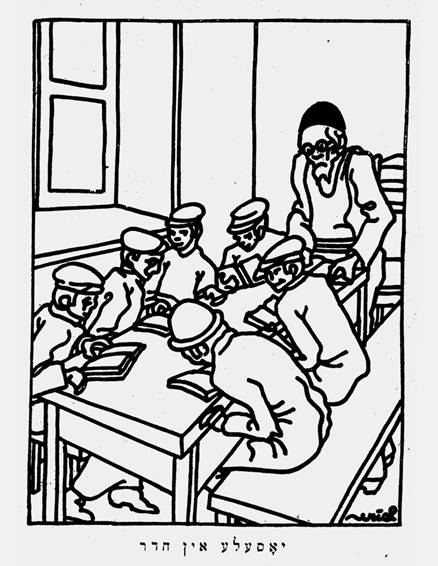

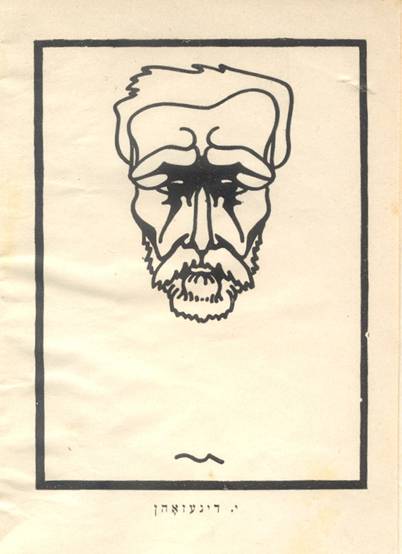

Subject: Uriel Birnbaum's "Yosele in Kheyder" and "Yankev

Dinezon"

Uriel Birnbaum's portrait of Yankev

Dinezon

Uriel Birnbaum's

"Yosele in Kheyder"

6)---------------------------------------------

Time: 11 May 2008

From: Robert Goldenberg

Subject: Dutch klezmer group plays "Holland Terkisher"

The SALOMON KLEZMORIM group was founded by the

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

End of The Mendele Review

Issue 12.010

Editor, Leonard Prager

Editorial Associate, Robert Goldenberg

Subscribers to Mendele (see below) automatically

receive The Mendele Review.

Send "to subscribe" or change-of-status messages

to: listproc@lists.yale.edu

a. For a temporary stop: set mendele mail

postpone

b.

To resume delivery: set mendele mail ack

c. To subscribe: sub mendele

first_name last_name

d. To unsubscribe kholile: unsub mendele

**** Getting back issues ****

The Mendele Review archives can be reached

at: http://yiddish.haifa.ac.il/tmr/tmr.htm

Yiddish Theatre Forum archives can be reached

at: http://yiddish.haifa.ac.il/tmr/ytf/ytf.htm

Mendele

on the web: http://shakti.trincoll.edu/~mendele/index.utf-8.htm

***