The

Mendele Review: Yiddish Literature and Language

(A Companion to MENDELE)

---------------------------------------------------------

Contents of Vol. 11.014 [Sequential No. 191]

Date: 30 December 2007

Dorfsyidn ('Rural Jews') – Part Two

1) This issue of TMR

(ed).

2) Notes on dorfsyidn ('rural

Jews')

3) On Mendel Mann's "Ven epl beymer

blien"

4) Books

Received

5) Periodicals Received

6) Symposium Announcement

1)-------------------------------------------

Date:

From: ed.

Subject: This issue of TMR

*** An

agricultural-lexicographic note: the last issue of TMR

lists suggested glossary corrections. Harkavi directs the user of his

dictionary from shenik to the dialectal syenik. His English

definition of the word is 'hay mattress' and not Professor Taube's 'straw

mattress' (the text has "in shtroy fun shenik"). However, Harkavi's

Hebrew definition is khatsir, whose meaning may be 'kash' or 'teven',

i.e. 'straw'. Hay (Yiddish hey) and straw (Yiddish shtroy) are

not the same. Straw is cheaper than hay and hay has more seeds. Hay is the

first cutting from the hay fields, the top growth of the plants. Straw, cut

afterwards, is the stalk of the plants. ***We now go on to a brief discussion

of those Jews in Eastern-European derfer or small countryside shtetlekh,

loosely naming all of them dorfsyidn, who most certainly knew this

distinction. (Mordkhe Schaechter's Plant Names in Yiddish [New York: Yivo, 2005]

brings evidence of a rich Yiddish botanic terminology.) The general discussion

of dorfsyidn serves as background to an analysis of Mendel Mann's

chapter "Ven

epl beymer blien" in his

autobiographic Di yidish-poylishe milkhome. *** We conclude with

sections on books and periodicals received and an announcement of a one-day

symposium at Leyvik House in Tel Aviv on January 3, 2008.

2)-------------------------------------------

Date:

From: ed.

Subject: Notes on dorfsyidn ('rural Jews')

In his

hilarious early novel Coming from Behind (New York: St. Martin's

Press, 1983), Manchester-born Howard Jacobson effectively mines the stereotype

of the Jew as city creature, stranger to country and country ways, hardly ever

a farmer. Here is his hero, Sefton Goldberg:

"Being

Jewish, Sefton did not know much about the names or breeds or needs of

fish." [p. 20] "He often struck Sefton as resembling a little English

garden bird, though which garden bird Sefton Goldberg, being Jewish, couldn't

be expected to know." [p. 22] "Charles, I'm Jewish. What am I going

to do in the country? I don't own a pair of

The country

Jews who leased or owned kretshmes ('inns') or raised, sold, processed

or in some other manner dealt with the raw materials for manufacturing spirits

of various kinds – knew about beer and they had terms for numerous plants in

their environs. They were Sefton's cousins who belonged to a different world.

As with many stereotypes there is at least a crumb of truth in the

careless generalization that Jews don't engage in agriculture. Statistically,

especially in Western Europe and

Judaism in its

halachic culture preserves memories of an agricultural past (e.g. see the

Mishnaic Seder Zeraim) and among the Orthodox numerous

rules and customs relating to agricultural products and practices continue to

apply (see http://www.webshas.org/lead/food.htm).

But it was precisely because of their country way of life, their distance from

synagogues and study houses, mikves and cemeteries – from all the institutions

required to maintain a traditional Jewish life – that yishuvnik became

a demeaning term, name for an ignoramus, a

blockhead, an uncultivated country bumpkin. Manual labor in general

tended to be looked down upon and shnayder ('tailor') enjoyed more prestige than a shuster (cobbler). The farmer

had to carry out certain chores at certain times and this made city life

Judaically more attractive. The term yishuvnik can often be found in

Yiddish literature in a pejorative sense. There are, however, many exceptions:

instances where the yishuvnik, (possibly because of his exceptional character

or achievements in business or learning) while referred to as a yishuvnik

is nonetheless respected. Shtetl and village Jewish life are often

sentimentalized in Yisker bikher accounts, but judicious surfing can

gather up much objective information. What follows are excerpts and paraphrases

from a number of websites, including several from excellent JewishGen reports.

***

1. Yishuvniks

could be prosperous, owners of fields, etc. --

The

"Yishuvnik" had fields, cows, a house, and most important - a Torah….

Mother, Father and the other Vishniveans would walk 6 km to the Shtetl Rosh

synagogue to pray and be among Jews. This was not convenient both for the Jews

in Rosh who felt too crowded and for the Vishniveans. Finally they decided to

stay in the village and pray at the "Yishuvnik". He was a

"Shmid" (blacksmith) and disabled. He had a wooden leg below his

knee…. His house served as a small synagogue for the daily "Minyan."

(see http://vishnive.org/e_viho.html).

***

2. Many country (and small shtetl) Jews kept

vegetable gardens (as well as

cows, goats, chickens, etc.): Gardening in Ivenets

The

Christian and the Jewish residents of

***

3. Ora of Ivenets -- no ordinary yishuvnik (Translation

of Sefer Iwieniec, Kamien ve-ha-seviva; sefer zikaron, Tel Aviv, 1973.

But after Yom

Kippur a serious question arose, what to do in order to build a new bath house.

A bath house is one of the most essential public needs, without which no Jewish

community can exist…. The Holy One sent them a redeemer, a farm-dwelling

[yishuvnik] Jew named Ora Brikovshtziner, or Aaron of the

Ora was no

boor, but neither was he a great scholar. He could read a chapter of Mishna and

understand it superficially, but he was a good businessman. He leased a flour

mill and some land from one of the landowners, and built a brewery in the

village, which made him rich. Since he was a yishuvnik who belonged to Ivenets

(he owned the house where the town's rabbi lived), he donated lumber from his

woods to build the bath house, gave some cash, and paid the builders…. Ora had

one ambition -- to buy pedigree for his money. He married his son off to a

daughter of one of the most illustrious families of that time -- the daughter

of the great Rabbi Israel Salanter. [For

dishonest business practices] Ora was sent to

***

4. Yekhezkl Kotik's father, a zealous hasid,

could not bear to pray with misnagdim yishuvniks

From TMR vol. 4 no.

3:

gedavnt hot

der tate shabes oykh in der heym, khotsh ale yishuvim fun a vyorst, tsi fun

tsvey vyorst arum, kloybn zikh oyf, loyt der traditsye, tsu eyn yishuvnik

davnen shabes mit a minyen. in aza minyen leyent men oykh di toyre, vi es firt

zikh umetum: tsvey yishuvnikes, gaboim,

rufn oyf tsu der toyre. es iz oykh do sine, kine far alies. yederer vil di

fetere aliye, un di gaboim kenen keyn mol nisht yoytse zayn. teyl mol

kumen derfun aroys groyse makhloykesn

biz masrn oder biz oysdingen bay

yenem zayn kretshme, tsi zayn pakt.

der tate hot

keyn mol nisht gevolt davnen mit di yishuvnikes misnagdim, nor az es hot gefelt

tsum minyen, flegt er muzn kumen. ober er flegt bay zikh nisht kenen poyeln tsu

davnen mit zey betsiber. er flegt shoyn demolt hobn ongegreyt bay dem yishuvnik

a medresh oder a zoyer un flegt

beysn davnen kukn in di sforim. gedavnt hot er in der heym far zikh.

***

5. Shmarya Levin [1867-1935] was born and grew up

in Swizlowitz, a shtetl at the confluence of the Svisla and

***

6. In Der fremder ('The Stranger') by

Y.-Y. Zinger (I.J. Singer) we see one

pattern wherein the sole Jewish farmer in a village is forced to leave for the

greater security of a Jewish community in a town. I concluded my commentary on

the story as follows: (see TMR vol. 3 no.

11)

The point is

not that Jews can only live among other Jews -- this is obviously not so

historically and actually -- but that Jews (or any other group with a highly

defined moral code of its own) cannot be integrated in societies whose mores

and manners conflict sharply with their own.

Traditional Jewish religious and communal life requires a certain

concentration of Jews in a circumscribed area to fulfill ritual needs, but the

hero of our story is a yishuvnik who davens but obviously can not maintain the

higher degrees of observance. Yet it is

not because of difficulties in observance -- one reason that yishuvniks left

their farms for city or town -- that Refoyl must leave Lyeshnovke. Following

... the ostracism imaged in the breaking of all his windows, he felt he must

abandon his native village. Ironically,

in the town or city to which this yishuvnik will move, he is more than likely

to remain always a rustic outsider, "a fremder."

***

7. The first two paragraphs of Leyb Rashkin's Di

mentshn fun Godlbozhits introduce

us to a dorfsyid who has prospered in his village and seems comfortable

there, yet who is eventually drawn to the nearby town with its many religious,

social and other advantages. See http://yiddish.haifa.ac.il/PDF%20Stories/di_mentshn_leyb_rashkin.pdf

3)-------------------------------

Date:

From: ed.

Subject: Mendel

Mann's "Ven epl beymer blien" [Commentary]

"Ven

epl-beymer blien": A

The central

theme of "Ven epl-beymer blien" ('When Apple Trees Blossom') --

albeit expressed in a daytshmerism in the very opening sentence -- is

awakening: "Arum Shvues hobn mayne feters dervakht." The story (which

can be read as fiction whether or not it attemps to report real persons and

events or is an imagined narrative) begins at dawn before Shvues (a harvest

festival) in a shtetl in

Uncle Elye

goes to the synagogue at the break of day and from gossip that inevitably

arises when neighbors meet he learns that so

and so's orchard remains unleased, a particular peasant is selling two

cows, and other news which will determine his day's movements. He is happily

pious, as a hasid should be: "Der feter Elye, tsurikgeyendik fun der shul,

nokhn shakhris, hot oysgezungen far zikh aleyn, shtilerheyt, etlekhe psukim fun

tilim (*) -- "Hashmieyni va-boker khasdekho" un zey glaykh iberzetst

in yidish, azoy vi der feter volt gevolt, az nisht nor der reboyne-shel-oylem

zol im farshteyn, nor oykh der zamdiker shliakh...." [p. 42]. Prayer and

commerce mingle in an easy alliance as Uncle Elye sings out: "Oy oy,

gotenyu, loz mir hern in frimorgn dayn khesed, vorem oyf dir hob ikh mikh

farzikhert"... In preparation for the day's business, he takes money from

a straw mattress on a bed in the same room where his nephew, Menakhem, has been

sleeping and may have seen what transpired. Elye's sudden notion to take

Menakhem with him for the day's dealings is at least partly born of a fear that

his hiding place might be accidentally revealed by his nephew to beggars

passing through the shtetl or to others.

This suggestion of possible evil helps make the near-idyllic atmosphere

of a wholesome pastoral life more believable.

When Elye and

the soon-to-become a bar-mitsva, city-bred Menakhem, arrive at the estate of a

Polish nobleman to lease an orchard, the dogs bark fiercely and they are turned

away by the gate-keeper. They learn that the baron has been drinking hard,

fighting with his wife, whipping his best horse mercilessly and had ordered

that no one be allowed to enter the farmyard. Elye loosened his horse's reins

and lay down on the grass, singing his earlier refrain with a surprising

addition: "Hashmieyni va-boker khasdekho... ay,ay,ay... to vos eytsestu

mir, Menakheml" ('What do you advise me to do, Menakheml?') The boy

presumably remained speechless; the uncle fell asleep. It is during his nap

that events occur which Elye has not directly influenced and in which rancor is

transformed to amicability. The uncle's prayers are answered, but this is not

the prime meaning of what occurs during his sleep. That meaning is the

experience of Menakhem.

The

landowner's young daughter came out of doors after being indoors for a long

period. She was delighted to have a young companion with whom to chase

butterflies and soon invites him home. "Zi hot nisht aroysgelozt Menakhem's hant un

ir fremder otem hot im tsuersht gelokt, dernokh opgeshtoysn." ['She did not let go of Menakhem's hand and her

strange breath at first attracted but afterwards repelled.'] The boy is welcomed by the landowner's wife and the nobleman's anger subsides. He is

so delighted by his daughter's happiness and his wife's softening that he

leases his orchard to Uncle Elye at extremely favorable terms – with the

condition that Menakheml spend the summer, the picking season, on the estate

where he can be a companion to his much isolated little daughter.

Elye and

Menakheml set out for home, Elye pleased that he need not continue his business

pursuits that day (by buying the peasant's two cows as originally planned). He

is teaching Menakhem the virtues of moderation and of graciousness in business

matters by making him a partner in the orchard transaction which the nephew had

made possible . The boy, sensing the uncle's indebtedness, sees the opportunity

to ask to take the horse's reins while they ride home; the uncle agrees, counseling him to ride at a

leisurely pace, not whipping the horse. "Menakhem hot gekukt

oyf gots velt un a benkshaft mit a troyer hot im arumgenumen nokh epes vos iz

vayt un umbakant". [my emphasis –

ed.] ['Menakhem looked out at God's world and was seized by a sad longing for

something distant and unknown'.] One can

almost hear Wordsworthian intimations in this line. The author shows his

psychological grasp of the pains of growing up. So much is attractive,

confusing and disturbing – the beauty of nature which demands response, the

responsibilities of material life (leasing an orchard), the hierarchies of

class and wealth (the nobleman's estate and family), human behaviors (anger and

love), the mystery of sex (the lovely young Polish girl held his hand), the

familiar and the unknown (uncle's home and the silent backroads), power over

some other – even a dumb animal. In short, awakening.

Mendel Mann's

concluding paragraph is masterful:

"Di erev Shvuesdike sheynkeyt fun di poylishe botshne vegn hobn im

geshrokn. Er hot gevolt oyfvekn dem feter un nisht gevakt. Dos ferd iz gegangen

shpan nokh shpan, nisht gekukt oyf der shalve, hot es azoy vi oysgefilt dem

umru fun yidishn yingele un zikh umheymlekh tsehirzhet." [' The Shvues eve beauty of the Polish

backroads frightened him. He wanted to wake his uncle but did not. The horse

trotted on, pace after pace. Oblivious of the evening's calm, it countered the

young Jewish boy's uneasiness with an uncanny neighing'.]

4)------------------------------

Date:

From: ed.

Subject: Books received.

àÇìò÷ñàÇðãòø

ùôÌéâìáìàÇè – âøéðòø àåîòè, ìéãòø – úì-àÈáéá: ä. ìééååé÷ ôÏàÇøìàÇâ, 2007

Aleksander Shpiglblat.

Griner umet; lider. Tel-Aviv: H. Leyvik Farlag, 2007

Three poems

from Shpiglblat's most recent volume of verse, Griner umet, are given

here, ample evidence that he stands at the very apex of the dwindling group of

Israeli Yiddish poets of stature. His style is spare and each poem of his is

masterfully etched. He is also, or even primarily, one of

àÇ ôÏøòîã÷Öè

àÇ ôÏøòîã÷Öè àÇ ÔÖÇñò

èåè æéê àÈï àÕó îéø

Ôé ãòí æÖãðñ ÷éèì

ÔàÈñ òø ôÏìòâ àÈðèàÈï

ôÏàÇø ëÌÈìÎðÄãÀøÆé,

ëÌãé öå æÖÇï àÈôÌâòùÖãè

ôÏåï òåìíÎäæä

Ôé àÇ îú.

áòð÷ àéê àÇöéðã

ðàÈê ãòí äÖîéùï áâã

ÔàÈñ àéê äàÈá ôÏàÇøæòöè

áÖÇí ìàÈîáàÇøã ôÏàÇø àÇ çìåí

àéï àÖðòí îéè èìéúÎàåïÎúÌôÏéìï

àåï ÷òï æÖ ùÕï àéöè

îòø ðéè àÕñìÖæï.

[ææ' 42-43]

áòð÷ùàÇôÏè

Nur wer die Sehnsucht kennt,

Weiss, was ich leide!

Goethe, Lied

der Mignon

ãé áòð÷ùàÇôÏè àéæ àÇï àÈôÏòðò ÔåÌðã,

ÔàÈñ ðàÈø ãòø èÕè ÷àÈï æé äÖìï.

àÈáòø, çìéìä, ãé áòð÷ùàÇôÏè æàÈì ôÌìåöòí

æéê Ôòìï àÈôÌèàÈï ôÏåï îéø.

òñ èøéôÏè ôÏåï ãòø áòð÷ùàÇôÏè ÷àÈìéøé÷òø öòø,

àåï îÖÇðò èÕèò ÷ìàÈâï àéï àéø.

æàÈì îéê, çìéìä, ãòø âåøì ðéè ùèøàÈôÏï

àåï àÈôÌèàÈï ãé áòð÷ùàÇôÏè ôÏåï îéø.

[ææ' 34-35]

áòðèùï, áòðèùï

øá÷ä áàÇñîàÇï äàÈè

âòìÖòðè ãòí ôÏéøÎàåïÎðÖÇðöé÷Îéòøé÷ï ôÌàÈòè àÇáøäí ñåö÷òÔòø ôÏåï ãòí ÷àÇôÌéèì

„ãé âàÈìãòðò ÷Öè", àéï îÖÇï áåê

ãåøê

ôÏàÇøøÖëòøèò ùÖÇáìòê. àÕó øá÷äñ ùàìä ÔàÈñ æé æàÈì îéø ôÏåï æÖÇï æÖÇè

àéáòøâòáï, äàÈè òø àÇøÕñâòùòôÌèùòè ãé öÔÖ ÔòøèòøÓ „áòðèùï, áòðèùï".

áòðèùï, áòðèùï, äàÈè âòùòôÌèùòè

ø' àÇáøäí ñåö÷òÔòø äîùåøø,

àåï ãé áøëä æÖÇðò äàÈè àÇ áøé

âòèàÈï îéø èéó áîòî÷éí,

æéê âòìàÇùèùòè àåï âòöéèòøè îéø

àéï àÕòø,

àåï àéê äàÈá àéï àéø ãòøäòøè àÇ

úÌôÏéìäÎæëÌä.

------------------------------

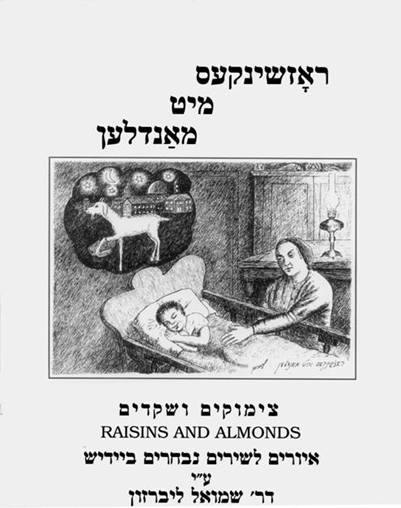

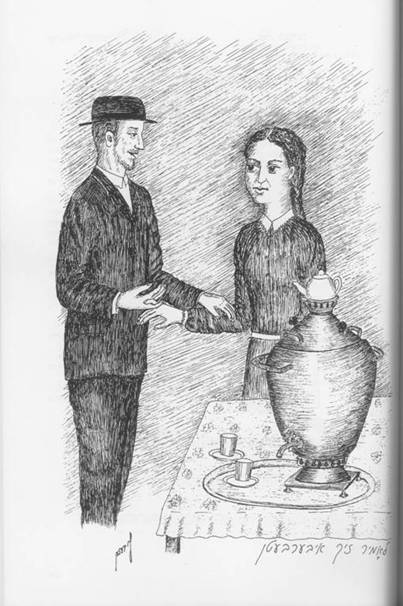

ãø' ùîåàì

ìéáøæåï –øàÈæùéð÷òñ îéè îàÇðãìòï, àéåøéí ìùéøéí ðáçøéí áééãéù – çéôä, 2007

Dr.

Shmuel Liberzon – Raisins and Almonds, illustrations to Yiddish songs.

In his

individual homely style,

5)-----------------------------

Date: 30 December 2007

From: ed.

Subject: Periodicals Received

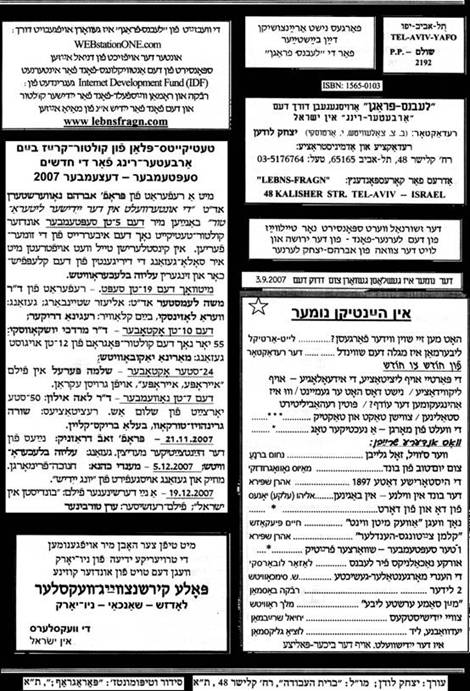

The veteran

Bundist periodical Lebnsfragn under the able editorship of Yitskhok

Luden continues to appear both in print (see Table of Contents below) and

online at http://www.lebnsfragn.com.

Lebns-fragn

Click on the picture to get a larger

resolution

--------------------------

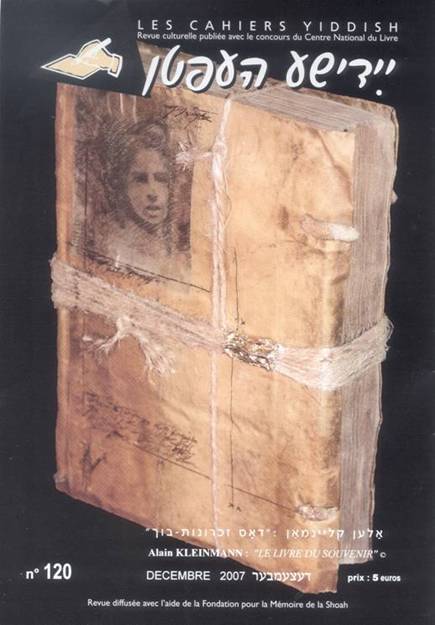

Yidishe heftn (its French name is Les Cahiers Yiddish) has been

published in

Yidishe

heftn/ Les Cahiers Yiddish

Click on the picture to get a larger

resolution

6)---------------------------------

Date:

From: ed.

Subject: Announcement:

The

Leyvik House in Tel Aviv cordially invites you to a symposium celebrating

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

End of The Mendele Review Vol. 11.014

Editor, Leonard Prager

Subscribers to Mendele (see below) automatically receive The

Mendele Review.

Send "to subscribe" or change-of-status messages

to: listproc@lists.yale.edu

a. For a temporary

stop: set mendele mail postpone

b.

To resume delivery: set mendele mail ack

c. To subscribe: sub mendele

first_name last_name

d. To unsubscribe kholile: unsub mendele

**** Getting back issues ****

The Mendele Review archives can be

reached at: http://yiddish.haifa.ac.il/tmr/tmr.htm

Yiddish Theatre Forum archives can be

reached at: http://yiddish.haifa.ac.il/tmr/ytf/ytf.htm

Mendele on

the web: http://shakti.trincoll.edu/~mendele/index.utf-8.htm

***