The

Mendele Review: Yiddish Literature and Language

(A Companion to MENDELE)

---------------------------------------------------------

Contents of Vol. 10.004 [Sequential No. 169]

Date: 12 April 2006 [Erev Peysekh]

NINTH ANNIVERSARY ISSUE

1)

This issue of TMR (ed.)

2) A bintl briv from the Forverts [1928] (Robert Goldenberg)

3) English translation of A bintl

briv from 1928 (ed.)

4) Review of Nancy Sinkoff's Out of

the Shtetl (Adam Teller)

5) Titular song of stageplay "Mayn

yidishe mame" (ed.)

6) Men meynt nit di hagode nor di

kneydlekh

7) 100th anniversary of poet Menke Katz

(1906-2006)

8) Letter to the Editor re "Mit

ale zibn finger" (Joseph Sherman)

Click here to enter: http://yiddish.haifa.ac.il/tmr/tmr10/tmr10004.htm

1)---------------------------------------------------

Date: 12 April 2006

From: ed.

Subject: This issue of TMR

This Passover issue marks the ninth anniversary of The Mendele Review, now a fairly familiar – and, it can (not immodestly) be said, respected name among lovers of Yiddish the world over. I hope that we continue to deserve this recognition and that it increasingly be acknowledgement of a highly cooperative effort. I thank all those who have helped these first nine years.

* This year marks, too, the 100th anniversary of the New York Forverts' Bintl Briv (1906), a highly popular feature of the leading Yiddish newspaper in North America. Its famous editor, Abe Cahan, initiated this column and in its earliest years answered letters as well. The selected letter from the year 1928 given in this issue of TMR – Yiddish original and your editor's English translation -- illustrates one kind of personal problem immigrant readers hoped to solve with the help of their newspaper. The Forverts was much aware of women's rights, yet here counsels in a conventional vein against what it sees as naivete in the face of a socially ambiguous man-woman situation.

* Dr. Adam Teller, a specialist in Polish-Jewish history at the University of Haifa reviews Nancy Sinkoff's Out of the Shtetl, a book which deserves the attention of TMR readers, especially those interested in that remarkable pioneer of modern Yiddish, Mendl Lefin of Satinow. See his translation of Koyheles: http://yiddish.haifa.ac.il/texts/mendl/Koh_Reyz_2002-07-24.pdf.

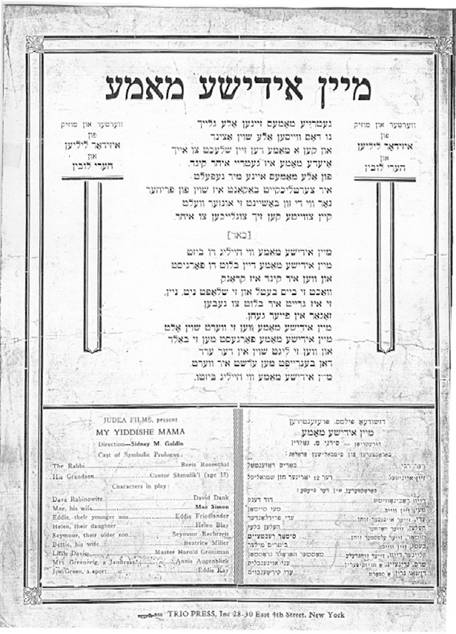

* The last issue of TMR (TMR Vol. 10, No. 3) featured one of the most famous songs in the Jewish -American repertoire, "Mayn yidishe mame," numerous versions of which exist in Yiddish, English and other (e.g. Dutch) languages. The title is also variously spelled and the musical arrangements follow suit in their variety. The whole story surrounding this song and its most famous singer could fill a monograph. Donald Clarke in The Rise and Fall of Popular Music [see http://www.musicweb-international.com/RiseandFall/4.htm] writes: "Tucker recorded ‘My Yiddishe Mama’ in 1928, in English on one side of the record and Yiddish on the other, and sold a million copies." It is this exemplar, rendered virtually scratchless by Jan Hovers, to which we linked. In the present issue of TMR we remind readers of another popular "Mame" – a stageplay called "Mayn yidishe mame," with a central theme song that in many ways parallels the Sophie Tucker lyrics. Both Yiddish original and an English translation (by the editor), are given, as well as a reproduction of the back page of the sheet music of the song. This page gives the Yiddish lyrics and Yiddish and English lists of the play's dramatis personae.

* The editor reflects on the saying "Men meynt nit di hagode nor di kneydlekh" ['They don't mean the Haggadah, but the dumplings'].

* "Mit ale zibn finger" apparently is a Yiddish idiom – see Joseph Sherman's letter below. While we are making progress in that we now have a concrete attestation, the history of the saying remains unknown. It does not seem to be recorded in any of our collections of proverbial or idiomatic sayings.

2)---------------------------------------------------

Date:

12 April 2006

From: Robert Goldenberg

Subject: A bintl briv from the Forverts (1928) [Americanisms

marked in red – ed.]

אַ בינטל

בריװ (אוג. 12, 1928)

[אַ מאַן װאָס לעבט גליקלעך און געטרײַ מיט זײַן פֿרױ, באַשרײַבט װי אַזױ ער פֿילט װען זײַן פֿרױ נעמט אױטאָמאָביל רײַדס מיט אַ פֿרײַנד. – אַלעס קומט פֿאַָר אױף אַן ערלעכן אופֿן, אָבער ער גלײַכט עס ניט. – ער באַשרײַבט זײַנע געפֿילן און זײַן פֿרױס האַנדלונגען װי אַן אינטעליגענטער און פֿײַן-פֿילנדער מענטש.]

װערטער

[װערטיק] רעדאַקטאָר.

איך בעט אײַך מיר צו געבן אַן עצה, איך װײס אַלײן ניט צי איך האַנדל ריכטיק צי נײן. מײַן פֿרױ טענהט, אַז איך בין אומגערעכט מיט מײַן האַנדלונגון. איך? – איך װײס ניט צי בין איך גערעכט צי נײן. איך װאַרט צו הערן פֿון אײַך אײַער מײנונג..

איך בין פֿאַרהײַרעט מיט מײַן פֿרױ צען יאָר צײַט. מיר זײַנען ניט רײַך, אָבער מיר לעבן זיך גליקלעך. מיר האָבן צװײ קלײנע קינדערלעך. איך פֿאַרדין ניט פֿיל. איך בין אַן אַרבעטער, אָבער איך מאַך אַ לעבן. איך האָב ניט קײן גרױסע אױגן. איך בין ניט מקנא מיט קײן רײַכטום. איך פֿיל, אַז גליק ליגט ניט אין רײַכטום. אױב מען איז גאָר צופֿרידן איז מען גליקלעך.

לעצטנס איז מײַן פֿרױ באַקאַנט מיט אַ רײַכן מאַן און ער קומט איר געבן רײַדס אױף זײַן מאַשין. זי פֿאָרט אָפֿט מיט אים צוזאַמען מיט די קינדער. זי טוט דאָס ניט איך זאָל ניט װיסן. איך װײס פֿון אלעס. זי דערצײלט, אַז דער מאַן איז אַ פֿײַנער און אַזױ װי די קינדער ענדזשױען שטאַרק דעם רײַד פֿאָרט זי מיט אים. דער מאַן קומט אָפֿט אױך מיך נעמען פֿאַר אַ רײַד, אָבער איך אַנטזאָג זיך מיט אים צו פֿאָרן. איך געפֿין תּמיד אַ תּירוץ אױף ניט צו פֿאָרן. עפּעס שמעקט מיר ניט דער אומזיסטיקער רײַד. איך קען ניט פֿאַרשטײן פֿאַר װאָס זאָל דער מאַן מיך אַרומפֿירן אױף זײַן מאַשין. פֿאַר װאָס פֿיֿרט ער ניט אַנדערע ייִדן?

מײַן װײַב

איז אין כּעס אױף מיר פֿאַר װאָס איך אַנטזאָג זיך מיט אים צו פֿאָרן. דאָס איז,

זאָגט זי, אַ באַלײדיקונג. אָבער איך פֿיל, אַז אַנדערש קען איך ניט האַנדלען.

און לאָמיך

זיך מודה זײַן׃ מיר געפֿעלט שטאַרק ניט פֿאַר װאָס מײַן װײַב פֿאָרט מיט אים.

ס'איז אמת, אַז מײַן װײַב איז אַן ערלעכע און נאַרט מיך ניט. אָבער דאָך, פֿאַר

װאָס קומט ער זי נעמען אױף רײַדס? װאָס האָט ער אױף

איר דערזען?

מײַן װײַב

זאָגט, אַז ער איז זײער באַפֿרײַנדעט מיט איר. ער גלײַכט

מיט איר צו רעדן. זאָג איך איר׃ ניו יאָרק איז אַזאַ גרױסע שטאָט, האָט ער שױן ניט

געפֿינען מיט װעמען צו רעדן, נאָר מיט

דיר? זאָגט זי , אַז איך בין אײפֿערזיכטיק. זאָג איך, אַז דאָס האָט ניט צו

טאָן מיט קײן אײפֿערזוכט. דער פּשוטער שׂכל דיקטירט, אַז װען א מאַן קומט אַ װײַבל

נעמען פֿאַר רײַדס, מײנט ער עפּעס דערמיט. זאָגט

מײַן װײַבל׃ – „װאָס זשע ביסטו מיר חושד, אַז איך האָב אים ליב?“ זאָג

איך: נײן, איך װײס, אַז דו האָסט קײנעם

ניט ליב אַ חוץ מיך, אָבער יענער מײנט עפּעס. ער זוכט בײַ דיר ליבע. ער אַרבעט אױף

דעם. ער אַרבעט לאַנגזאַם. ער האָט אפֿשר אַ שװערן דזשאַב,

אָבער ער טרײַט.

מײַן פֿרױ

האַלט זיך בײַ אירען, אַז יענער איז זײער אַ פֿײַנער מאַן און אים װעט ניט קומען

אפֿילו אױף די געדאַנקען צו שפּילן אַ ליבע מיט אַ פֿאַרהײראַטע פֿרױ. און זי

דערצײלט מיר, אַז זי זאָגט אים אָפֿט װי ליב זי האָט איר מאַן און אים געפֿעלט

דאָס זײער, זאָגט ער, װאָס אַ פֿרױ האָט ליב איר אײגענעם מאַן.

קורץ, איך

מיט מײַן פֿרױ דעבאַטירן די פֿראַגע, און דערװײַל נעמט מײַן פֿרױ אַלע װאָך רײַדס. צװײ מאָל אַ װאָך, דרײַ מאָל אַ װאָך. װיפֿל

געלעגנהײטן זי האָט נאָר.

און װאָס

ערגער איך זוך אַלץ מער װעגן מײַן פֿרױס פּלעזשער.

איך װיל איר ניט שטערן. איך האָב זי זײער ליב. איך װײס אַז זי פֿאָרט מיט אים

מײנסטנס צוליב די קינדער. זי װיל, אַז די

קינדער זאָלן זיך אַמוזירן. אָבער דאָך,

-- פֿאַר װאָס פֿאָרט ער מיט מײַנע קינדער? ער קען דאָך פֿירן אױף דער מאַשין

נעענטערע מענטשן װי מײַן װײַב און קינדער.

ער האָט דאָך אײגענע פֿאַמיליע.

איז ניט

גענוג װאָס איך מאַטער דאָס אַזױ שטאַרק, טענהט מײַן פֿרױ אַז ס'איז אַן עװלה

װאָס איך פֿאָר אױך ניט מיט דעם מאַן אױף דער מאַשין. דער מאַן פֿילט זיך

באַלײדיקט װאָס איך װיל קײן מאָל ניט פֿאָרן, און אַזאַ פֿײַנעם מאַן דאַרף מען

ניט באלײדיקן, טענהט זי. איך פֿיל אָבער בײַ זיך, אַז װען איך װאָלט געפֿאָרן מיט

דעם מאַן, װאָלט ער געפֿילט שלעכט אין מײַן קאָמפּאַני.

מיר דוכט זיך, אַז װען דער מאַן טוט מיך אַ קוק

אָן זײט ער, אַז איך בין אױף אים אַ מבֿין פֿאַר װאָס ער פֿירט מײַן װײַב אױף דער מאַשין. מיר דוכט

זיך, אַז ער קען מיר ניט קוקן גלײַך אין

די אױגן אַרײַן.

און אַ מאָל טראַכט איך, אפֿשר בין איך אומגערעכט. אפֿשר מײנט דער מאַן גאָר ניט, נאָר גלאַט פּשוטע פֿרײַנדשאַפֿט און איך איבערטרײַב אין מײַן פֿאַנטאַזיע צוליב אײפֿערזוכט. טאָ װער קען װיסן װאָס ס'איז דער אמת. איך האָב דערפֿאַר באַשלאָסן בײַ אײַך צו פֿרעגן אַן עצה. װי דענקט איר, הער רעדאַקטאָר, פֿאָרט דער מאַן צוליב פּשוטער פֿרײַנדשאַפֿט צי האָט ער שלעכטע געדאַנקען? אױב ער מײנט ניט קײן שלעכטס, טאָ פֿאַר װאָס זאָל איך אים מאַכן פֿילן שלעכט, און טאַקע אױך ניט נעמען אַ רײַד מיט אים? אױב ער האָט אָבער אַ געדאַנק דערבײַ, טאָ פֿאַר װאָס זאָל איך מײַן װײַבל לאָזן פֿאָרן מיט דעם מאַן און עס לאָזן אַרײַנטרײַבן אין דער װײַטער באַנק אַרײַן? װי איר װעט זאָגן, אַזױ װעל איך האַנדלען.

מיט

אַכטונג,

אַ מאַן

װאָס דענקט , אַז ער איז ניט אײפֿערזיכטיק.

———————————————————-

[ענטפֿער]

צי דער

מאַן מײנט עפּעס מיט זײַנע אױטאָמאָביל רײַדס, צי

ער מײנט ניט, דאָס קענען מיר ניט זאָגן, װײַל מיר קענען ניט װיסן װאָס ער מײנט,

און װאָס ער מײנט ניט.

עס קען

זײַן, אַז ער איז אַ פֿײַנער מאַן און מײנט נאָר פֿרײַנדשאַפֿט; ער קען אױך זײַן

ניט קײן פֿײַנער מאַן און אױך ניט מײנען פֿרײַנדשאַפֿט, און ער קען זײַן גאָר

אַ פֿײַנער מאַן און עפּעס מײנען אַנדערש

אַחוץ פֿרײַנדשאַפֿט.

בכּלל

איז דער חשק פֿון ליבע ניט שײך צום פֿײַנעם מאַן אָדער ניט צום פֿײַנעם מאַן. מען

קען זײַן זײער אַן ערלעכער און פֿײַנער מאַן און דװקא ליב האָבן יענעמס װײַב. מען

קען זײַן אַ פּאַסקודנער מאַן און דװקא ליב האָבן בלױז די אײגענע װײַב.

אַלזאָ, װאָס מיט יענעם מאַן מיטן אױטאָמאָביל איז דער

מער, װײסן מיר ניט. מיר װײסן אָבער גאַנץ

גוט, װאָס עס איז דער מער מיט אײַך און מיט אײַער פֿרױ, און װעגן דעם קענען מיר

זאָגן אונדזער מײנונג מיט באַשטימטקײט.

עס קען

זײַן, ניט עס קען זײַן, נאָר מיר זײַנען איבערצײַגט, אַז אײַער פֿרױ נעמט רײַדס אין יענעמס אױטאָמאָביל אױף אַן ערלעכן און

אומשולדיקן אופֿן, אָבער מיר זײַנען אײַנפֿאַרשטאַנען מיט אײַך און ניט מיט אײַער

פֿרױ.

עס קען

זײַן, אַז עס װאָלט גאָר ניט געשאַט, װען איר זאָלט יאָ נעמען אַ רײַד צוזאַמען מיט אײַער פֿרױ, אָבער מיר זײַנען

אײַנשטימיק מיט אײַך װאָס איר װילט ניט פֿאָרן.

איר

זײַט אַ מענטש מיט אױפֿריכטיקע געפֿילן אין אײַער האַרצן. איר פֿילט, אַז איר װילט

ניט פֿאָרן ; איר פֿילט, אַז װען איר װעט פֿאָרן װעט איר אױסקוקן אין אײַערע אױגן

נאַריש, און דערפֿאַר פֿאָרט איר ניט, און איר זײַט גערעכט.

אײַער

געגנגעפֿיל [קעגנגעפֿיל] פֿון ניט פֿאָרן

קומט ניט פֿון אײפֿערזוכט; עס קומט פֿון אַן אױפֿריכטיק געפֿיל װאָס אַ

דענקענדער מענטש האָט אין זײַן האַרצן.

איר

זײַט פֿולשטענדיק גערעכט.

אײַער

װײַב, װאָס נעמט רײַדס אומשולדיקערהײט, האָט אײַך

געדאַרפֿט פֿאַרשטײן און ניט פֿאָרן. איר פֿאָרן שטעלט אײַך אַװעק אין אַ

לעכערלעכע פּאָזיציע, און ס'איז פֿון איר זײער ניט טאַקטיש. נאָך מער אומטאַקטיש איז פֿון איר װאָס זי

װאַרפֿט אײַך אױף, אַז איר זײַט

אײפֿערזיכטיק. זי האָט אַ פּנים הנאה װאָס איר מאַן איז אײפֿערזיכטיק, און אין

דערײַן [אין דעם] ליגט די הנאה אירע פֿון די רײַדס.

מיר

זײַנען דורכױס געגן אײַער װײַבס אומטאַקטישער האַנדלונג, און מיר זײַנען

פֿולשטענדיק אײַנפֿאַרשטאַנדן מיט אײַך.

איר

קוקט אױף דער גאַנצער געשיכטע װי אַ דענקענדער מענטש מיט זעלבסט-רעספּעקט, און

אײַער פֿרױ באַציט זיך צו דעם װי אַ

צען-יאָריקע מײדעלע.

פֿאַר אַ צען-יאָריקע מײדעלע איז אַזאַ נאַיִװע באַציונג צו אַן אױטאָמאָביל רײַד שײן, אָבער ניט פֿאַר אַן ערװאַקסענע [אַ דערװאַקסענע] פֿרױ, קײן עין הרע.

[אױסגעקלאַפּט פֿון איציק גאָלדענבערג]

3) ---------------------------------------------------

Date: 12 April 2006

From: ed.

Subject: English translation of A

bintl briv from 1928

A Letter to the Editor, 12 August 1928

[A man who is faithful to his wife and lives

happily with her tells how he felt about her going on automobile rides with a

male friend. Though nothing disreputable was going on, he did not like it. He

describes his feelings and his wife's behavior intelligently and sensitively.]

Worthy Editor:

I would like you to advise me since I am not sure I am right. My wife says I am wrong. Am I? I don't know whether I am or not.

I have been married to my wife for ten years. We are not rich but we live comfortably. We have two small children. I am a worker and don't earn much but I make a living. My wants are few and I don't envy those who have more. I feel that happiness means being satisfied, not being rich.

Lately my wife has become acquainted with a rich man who comes to give her rides in his car. She often takes the children along on these rides, which she does not try to hide from me -- I know all about them. She says that the man is honest and that she takes the rides because the children enjoy them so. I too am invited to come along, but I refuse -- I always find an excuse for saying No. There is something about these free rides that makes me uneasy. I don't know why this man wants to drive me around in his car. Why doesn't he drive others around?

My wife is mad at me for refusing to accept a ride. She says this is like insulting him, but I can't behave differently. I admit I am strongly against my wife taking these rides with him. Of course my wife is honest and is not deceiving me, but why does he offer her rides? What does he see in her?

My wife says he is a good person. He enjoys talking to her. And I answer, "New York is a big city, can't he find somebody else to talk to besides you?"

And her answer is that I am jealous. Common sense tells us that when a man takes a married woman out for a ride in his car he has something in mind. To which my wife says, "What, you suspect me of being in love with him?" I say, "I know you don't love anybody but me, but that man has some intention. He wants your love. He is working toward that, working slowly. He may have a tough job before him, but he keeps trying."

My wife continues to believe that her friend is an honest man who would never even let the idea of having an affair with a married woman cross his mind. She emphasizes how often she has told him how much she loves her husband and how it pleases him to hear that a wife loves her spouse.

And at times I think maybe I'm wrong. Maybe the man means nothing more than simple friendship and out of jealousy I exaggerate matters. Who can know what the truth is? That is why I am asking your opinion. What do you think, dear Editor? Are these rides based on simple friendship or does the man harbor evil intentions? If he means no harm, why should I make him feel bad and why shouldn't I accept a ride from him?

But if he has some scheme, why should I let my wife go along with him till the matter turns serious? I will do as you advise.

Respectfully,

A man who does not consider himself to be jealous.

[Editor's reply]

We cannot say whether or not the man has some intention in offering car rides since we have no way of knowing his mind. He may very well be a fine man who is offering friendship; he may be a not very upright person with an evil mind; and he may be a fine man yet with something in his mind other than friendship only.

The desire for love has nothing to do with whether one is honest or not honest. One can be virtuous and yet be in love with another man's wife. One can be a scoundrel and yet love his own wife.

Therefore we say we have no idea what is wrong with the man with the automobile. But we do know, and with absolute certainty, what is wrong with you and your wife.

We could conceivably be wrong of course, but we think your wife is honest in her acceptance of the rides. Nonetheless we fully agree with you and not with your wife.

Perhaps it would do no harm if you went along on a ride together with your wife, but we completely understand your reluctance to do so.

You are a person with sound and healthy feelings. Your heart tells you not to accept rides and that you would look foolish in your own eyes if you did. Thus you don't accept rides and are right not to.

Your resistance to accepting rides does not come from jealousy, but from the sound heart of a reasonable human being.

You are absolutely right.

Your wife, who guiltlessly accepted rides, should have understood how you felt and should not have accepted them. Doing so placed you in a ridiculous light and was most tactless. Even more tactless was her accusing you of being jealous. She enjoys thinking her husband is jealous and this indeed is the source of the pleasure she gets in accepting the rides.

We are totally opposed to your wife's tactless behavior and we fully understand you. You see the entire matter as a self-respecting and thinking person would. Your wife has been acting like a ten-year old girl. For a ten-year old girl a naive view of the offered automobile rides has its charm, but not for a grown woman.

4)--------------------------------------------------------

Date:

From: Adam Teller

Subject: Review of Nancy Sinkoff's Out of the Shtetl

Nancy Sinkoff, Out of the Shtetl: Making

Jews Modern in the Polish Borderlands, Providence 2004 (Brown Judaic

Studies 336). 320+xviii pp.

Nancy Sinkoff's study of the intellectual and cultural roots of

the Haskalah – the enlightenment movement of Eastern European Jewry – furthers

our understanding of the development of the world's largest Jewish center in

the 18th and 19th centuries.

Shifting attention away from developments in the liberal societies

of central and western Europe, it significantly adds to the debate surrounding

the modernization of Jewish society. At

the heart of the book's thesis is the understanding that since pre-partition

Polish Jewry largely made up the demographic and social basis of modern

European Jewry, any history of the latter group must take into account the

experiences of the former. A significant result of this new focus is the

abandonment of the traditional idea that in the 18th and 19th

centuries change traveled across European Jewish society from west to

east. Instead, the author prefers to

talk of "'national' or 'regional' paths to becoming a modern European

Jew" – a formulation which does not privilege the German Jewish experience

over the Polish.

The basic paradigm of this study is, therefore, one of

modernization, viewed mostly in the liberal terms of legal emancipation,

educational reform, and resistance to religious fanaticism (i.e.

Hasidism). The author borrows the term

"moderate Haskalah" – better known from the internal struggles of the

Russian Haskalah in the 1860s and 70s – in order to describe the rather

conservative ideology developed by the book's main protagonist, Mendel Lefin

Satanover. His life (1749-1826) spanned many of the major changes undergone by

Eastern European Jewry as it entered the modern age: born into the estate

society of early modern Poland-Lithuania with its decentralized power

structures which allowed the Jews significant room for maneuver, Lefin died in

the rigid, centralized environment of Austrian Galicia, where Jewish life was

increasingly circumscribed by the state. Sinkoff argues convincingly that

Lefin's cultural program was not only a result of this situation but also aimed

to give the Jews of eastern Europe the tools to deal with the very particular

changes they were experiencing. In her

final chapter, some of the results of Lefin's work are examined in a discussion

of one of his most important followers, Joseph Perl.

The first four chapters of the book discuss Lefin's program in

some detail. A crucial point for

Sinkoff, discussed in the first chapter, is the importance of his

Polish-Lithuanian – or more precisely, Podolian – background in formulating his

world view. The author argues that the

influence of eighteenth century developments, such as the Frankist movement and

the emergence of Hasidism, which were felt particularly in that region, colored

Lefin's attitude towards the Berlin Jewish Enlightenment during his short

residence in

The importance of this approach is that it transforms the haskalah

of

The linguistic aspect of Lefin's cultural program, discussed in

chapter four, provides some clues as to how Sinkoff views this role. In discussing Lefin's project to translate the

Bible into Yiddish, she eschews the idea that his use of Yiddish expressed some

kind of proto-nationalist ideology or sentiment, arguing that his use of

Yiddish, alongside his more numerous Hebrew publications, sprang from the

desire of a typical enlightened intellectual to educate the masses. (It is

noteworthy that he translated the "philosophical" books of Proverbs

and Ecclesiastes, adding a Hebrew commentary in enlightenment spirit). In fact, by espousing Yiddish, Lefin was

providing an alternative to the German language orientation of the

By examining some of Lefin's lesser known writings still in

manuscript, Sinkoff shows that he viewed Yiddish as the legitimate language of

Polish-Lithuanian Jewry, rather than as the inherently corrupt language of the

uneducated Jews, who could only reach a decent cultural level by adopting

German. Moreover, Lefin felt that once

the Jews themselves produced literary works of a high standard, their language

would take its place among the respected languages of the world. However, in her examination of the bitter

debate around his Bible translations, Sinkoff argues that his use of Yiddish

represented an attempt to rework the Berlin enlightenment in

a form more suitable for eastern European Jewry. There is a difference of

nuance here, since arguing that Lefin was providing an alternative form of

Haskalah suggests a more independent stance on his part than claiming that he

was simply reworking Mendelssohn's ideas. Sinkoff does not choose between these

formulations, even though in doing so she might perhaps have shed light on the

important question Lefin's eminently sensible strategy of approaching Eastern

European Jewry in their own language failed to make

headway for so many decades to come.

Lefin's political activity is discussed in detail in the second

chapter and once again allows Sinkoff to examine her subject against his

Eastern European background – in this case the debates in Poland-Lithuania and

Tsarist Russia concerning Jewish reform at the end of the eighteenth and

beginning of the nineteenth centuries.

Some time during the early 1790s, Lefin began to enjoy the patronage of

the great magnate, Adam Czartoryski, a leading figure in Polish social and

political high society and a passionate proponent of enlightenment

ideology. It was this connection which

turned Lefin into a major player in the Jewish politics of the period. He developed a critique of Polish Jewry,

focusing on the sources of authority within their society, and suggested a

reform of the rabbinate under state supervision. His goals were twofold: to rationalize the

functioning of Jewish life, so cutting the ground from under the irrational (as

he perceived it) Hasidic movement and to deepen Jewish society's integration

into the apparatus of the modern state.

In his view, however, the Jews were not simply an object of reform, but

were to be active in reforming their own society. Unfortunately, the great optimism of the

enlightenment era came to nothing for Lefin and the other maskilim of his

generation, since neither the Four Year Sejm (1788-1792) nor Derzhavin's

"Committee for the Amelioration of the Jews" (1804) brought the

desired reforms.

Lefin's failure to effect any significant reform of Eastern

European Jewish society along enlightenment lines had an enormous effect on the

development of the later Haskalah.

Understanding that the Jews' ability to make their mark on political

developments was highly limited (his own influence on Derzhavin's committee

could only have been indirect), Lefin decided to turn his attention away from

politics to cultural work amongst the Jews with the particular goal of

combating the rigid conservatism of the Hasidic movement. The abandonment of the political arena by

Lefin – and following him, by the Haskalah generally - though not total, meant

that the Haskalah could never be anything but impotent in its attempts to

modernize Eastern European Jewish Society.[1]

This becomes clear in Sinkoff's fascinating exposition of Lefin's

philosophy in her third chapter. She

shows how Lefin, who was deeply influenced by trends in 18th century

psychology, epistemology, and natural philosophy (including Benjamin Franklin's

"Rules of Conduct"), used this knowledge in his polemics against

Hasidism. Though his success in

integrating the new ideas into a traditional rabbinic theology in order to

create a new array of arguments against the hated movement was remarkable, his

inability to halt its spread was no less significant. Sinkoff does not devote much attention to the

reasons for this failure, which is a shame because without some analysis of the

phenomenon, it is much harder to evaluate Lefin's life and work.

In place of such a discussion, Sinkoff devotes her last chapter to

a discussion of one of Lefin's pupils, the famous Galician maskil, Joseph

Perl. This is an excellent treatment of

one of the most important figures of the early Haskalah – in fact, he was

arguably more significant than Lefin himself.

In addition, the discussion here provides a valuable counterbalance to

the very hostile approach to Perl adopted by Raphael Mahler in his study of the

Galician Haskalah.[2] Sinkoff provides a balanced and detailed

account of Perl's work in the fields of education and religious reform,

discussing not only the modern Jewish school he established in Tarnopol, but

also his approach to the modernization of Jewish law as expounded in his

unpublished tract, Ueber die Modification der mosaischen Gesetze (Regarding

the Modification of the Mosaic Laws).

Interestingly, Perl's stance is a combination of the reform Jewish

ideology concerning the historical development of halakha with a social

conservatism which allowed him to propose only a limited range of changes

within halakha and minhag. In fact,

Perl's radicalism was not focused so much on the Jewish texts as on the rabbis

who interpreted them. Like his mentor,

Lefin, he proposed a far-reaching reform of the Polish rabbinate aimed at

presenting Jewish society with an attractive alternative to what he viewed as

the obscurantism of the Hasidic movement.

Though Sinkoff shies away from explaining the reasons for Perl's

failure, this chapter will be of great value for teachers and students of the

Galician haskalah.

This is an important and interesting study of the roots of the

haskalah in

Adam Teller

[1] On the political work of

the maskilim, such as it was, see: E. Lederhandler, The Road to Modern

Jewish Politics: Political Tradition and Political Reconstruction in the Jewish

Community of Tsarist Russia,

[2] R. Mahler, Hasidism

and the Jewish Enlightenment: Their Confrontation in

5)----------------------------------

Date: 12 April 2006

From: ed.

Subject: Mayn yidishe mame

Mayn idishe [yidishe] mame

[verter un muzik fun Izidor Lilyen un Heri Lubin]

(Click here for larger resolution)

Getraye mames zaynen ale glaykh

Nu dos veysn ale shoyn atsind

Un ken a mame den zayn shlekht tsu aykh

Ayede mame iz getray ihr [ir] kind.

Fun ale mames eyne mir gefelt.

In tsertlechkeyt [tsertlekhkeyt] bakant iz shoyn fun friher frier]

Nor vi di zun basheynt zi unzer [undzer] velt

Keyn tsveyte ken zikh tsugleykhn tsu ihr [ir]

[khor]

Mayn idishe [yidishe] mame vi heylig [heylik]

du bist

Mayn idishe mame dayn blut du fargist

Un ven ir kind iz krank

Vakht zi baym betl un zi shloft nit, neyn,

Zi iz greyt ir blut tsu geben [gebn]

Zogar [un vos iz mer] in fayer geyn.

Mayn idishe [yidishe] mame ven zi vert shoyn alt

Mayn idishe [yidishe] mame fargest men zi bald

Un ven zi ligt shoyn in der erd

Dan [demolt] begrayft [bagrayft = banemt] men ersht ir vert.

Mayn idishe mame vi heylig [heylik] biztu.

[English translation – ed]

My Jewish Mama

Mothers are all devoted

As everybody knows,

For how could a mother

Not adore her child?

One mother of storied tenderness

Especially pleases me;

She beautifies the world like the sun

And no one compares to her.

Chorus

My Jewish mama, how holy you are,

My Jewish mama, you spill your blood,

And when a child is ill

You never leave their side,

Ready to give your very blood

Or even walk in fire.

When a Jewish mama grows old,

She is soon forgotten,

And only when she is in her grave

Is her full worth grasped.

My Jewish mama, how holy you are.

6)-----------------------------------------

Date: 12 April 2006

From: ed.

Subject: Men meynt nit di hagode nor di

kneydlekh

The

Passover Seder-inspired folk expression "Men meynt nit di hagode nor di

kneydlekh" ('They don't mean the Haggadah, but the dumplings') is the

realist's (or cynics?) year-round stiletto to puncture disingenuous altruism of

all sorts. As Max Weinreich pointed out,

it was a handy saying among secular Yiddishists (see TMR Vol. 3, No. 4) for

whom (as for most people) "kneydlekh" meant some material,

tangible desideratum as opposed to the merely verbal substance of the Haggadah.

In Shirley Kumove's translation -- "It's not the Passover story he's

interested in but the dumplings" (in Words Like Arrows) -- the

literal level of this saying is clearly elicited and "kneydlekh"

points to a dish which (certainly today) is intimately associated with the

holiday of Passover (even though the dish itself may be eaten all year round).

The matter, however, is not so simple. It is complicated because Jews are complicated and not only do all observant Jews not eat kneydlekh at the Seyder, for a significant number of them the kneydl is virtually treyf ('ritually forbidden')! For the great majority that do eat kneydlekh at the Seyder, there is a raging debate as to how to prepare and serve them. This difference is not small and it ranges from the sublime and symbolic to the grossly gastronomic. To understand why some Jews will not consume a kneydl at the Seyder, one must know about gebrokts and non-gebrokts. An excellent recent exposition of this matter can be found in Rabbi Berel Wein's "Kneidlach [kneydlekh]," Jerusalem Post 17 December 2004 (updated 12 January 2006) and accessible on the internet by clicking: http://rabbiwein.com/modules.php?name=News&file=article&sid=854. Unlike the terms kosher and (less so) treyf which have made great headway from Jewish to general English, gebrokts and non-gebrokts [from Yiddish brokn 'to crumble'] are mainly understood in Hasidic circles. I have not found the term gebrokts in any Yiddish dictionary.

As we learn from several websites devoted to

"Jewish cooking", there are some cooks with strong feelings against

the use of any fat in the preparation of kneydlekh, whereas in a litvish

("Lithuanian") tradition fried fat, grivn (fried goose skin ),

raspberry jam or fried onions are placed in the heart of the kneydl and these

become "neshomelekh," 'little souls' that "spiritualize"

the dish. One Mendele participant a few years back suggested some relationship

with the "neshome yeseyre" [second soul which the Jew possesses on

the Sabbath]; if we understand the term "neshome yeseyre" as meaning

'elevating element' then this reading becomes credible.

It is of linguistic interest to watch the

competition between the spellings kneidlach [i.e. dialectal, very

widespread among English-speakers] and this writer's preferred kneydlekh

[following the rule-guiding Standard Yiddish Romanization]. Extremely popular

synonyms are "matzo-balls" [also spelled "matso-balls" and

almost always pronounced in the Yiddish manner "ma'tse-balls"] and

the fully "assimilated" dumplings. For many people the term

"matse-balls" has an inherently comical ring, at least partly because

of the punning potential of the second element. Clearly, kneydlekh by

any other name would not be kneydlekh. . . .

7)-------------------------------

Date: 12 April 2006

From: Dovid Katz

Subject: 100th anniversary of poet Menke Katz (1906-2006)

A posting of a small selection of poems to mark Menke Katz's 100th anniversary may be found at: http://www.dovidkatz.net/menke/menke_19poems.htm

8)-----------------------------------------------

Date: 12 April 2006

From: Joseph Sherman

Subject: Letter to the Editor re

"Mit ale zibn finger"

Dear Editor,

I recall that in translating Dovid Bergelson's Opgang I ran across the idiom "mit ale zibn finger" or a cognate version of the idiom. I wrote to the distinguished folklore specialist Professor Dov Noy about it, and he was generous enough to send me a detailed answer in which he gave me several sources and explanations, attesting to the fact that this is indeed a Yiddish idiom which has a Biblical source in the various connotations (sacred and mystical) of "seven". There is no question that the idiom is genuinely Yiddish and that Bergelson uses it in the very sense in which Chagall illustrates it.

Sincerely yours,

Joseph Sherman

Oriental Institute

Pusey Lane

OXFORD OX1 2LE

England (UK)

----------------------------------------

End of The Mendele Review Vol. 10.004

Editor, Leonard Prager

Subscribers to Mendele (see below)

automatically receive The Mendele Review.

Send "to subscribe" or change-of-status messages to: listproc@lists.yale.edu

a.

For a temporary stop: set mendele mail postpone

b. To resume delivery: set mendele

mail ack

c. To subscribe: sub mendele

first_name last_name

d. To unsubscribe kholile: unsub

mendele

****Getting back issues****

The Mendele Review archives can be reached at: http://yiddish.haifa.ac.il/tmr/tmr.htm

Yiddish Theatre Forum archives can be reached at: http://yiddish.haifa.ac.il/tmr/ytf/ytf.htm

***