The

Mendele Review: Yiddish Literature and Language

(A Companion to MENDELE)

---------------------------------------------------------

Contents of Vol. 10.003 [Sequential No. 168]

Date: 27 March 2006

1) This issue of TMR (ed).

2) Artists' Portraits of Yiddish Writers, 2nd Series (David

Mazower)

3) Two languages locked in embrace: Hebrew and Yiddish (Zelda Kahan

Newman)

4) A Reply to Ghil'ad Zuckermann on "Israeli" (Amitai HaLevi)

5) Remembering Sophie Tucker (1884-1966)

a. A general description of Sophie

Tucker's life

b. "Mayn yidishe mame" in

Yiddish by Sophie Tucker, 1928 – audio file (Jan Hovers)

c.

Yiddish text of "Mayn yidishe mame" (ed.)

d. Romanized text of "Mayn yidishe

mame" (ed.)

e. "Mayn yidishe mame" in

English by Sophie Tucker, 1928 – audio file

(Jan Hovers)

f.

Sophie Tucker's 1928 Dutch "Mayn yidishe mame" record

illustrated (Jan Hovers)

g.

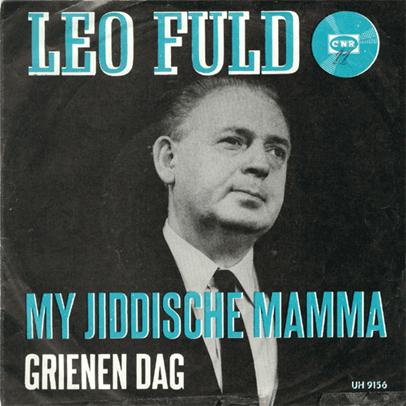

Leo Fuld's Dutch record of "Mayn yidishe mame" illustrated

(Jan Hovers)

6) Adina Bar-El's Grininke beymelekh – a further notice (ed.)

Click here to enter: http://yiddish.haifa.ac.il/tmr/tmr10/tmr10003.htm

1)----------------------------------------

Date: 27 March 2006

From: ed.

Subject: This issue of TMR.

This issue is richly attuned

to both eye and ear. *David Mazower continues his project, begun in TMR vol. 10, no.2, of displaying

portraits of Yiddish authors by graphic artists of note. *Zelda Kahan Newman

and Amitai HaLevi respond to Ghil'ad Zuckermann's writings on

"Israeli". *The fortieth

anniversary of Sophie Tucker's death is marked by featuring the great

comedienne singing that masterwork of deep nostalgia, "Mayn yidishe

mame" (also known as "A yidishe mame"), a classic in the

Jewish-American musical repertoire, and an historical marker as well of the

heroic immigrant experience. A 1928 Dutch 78'' recording provided by Jan

Hovers' site (www.78rpm.hovers.nl) gives us the basic Yiddish version on one side and an English version

on the other. The Tucker items in this issue begin with a useful link to a

review of the singer's life that does not omit her significant feminist and progressivist

contributions. The song "Mayn yidishe mame" can be heard in its two

versions and the picture of the actual 78'' record is given. An additional

Dutch version of the same song sung by Leo Fuld is also illustrated here. This

rich material is gathered here thanks to the generosity and cooperation of Jan

Hovers. The transcription of the lyrics of the song, in Yiddish and in Latin

letters, is by the editor. He was assisted in identifying a number of hard-

to-distinguish words by Ben-Zion Ronen. If TMR readers hear other words,

they are invited to let us know what they are. Readers will of course catch the

Americanisms (e.g kitshn 'kitchen') and the dialecticisms (e.g. fin [fun]

'from'). *Please note the revision in

the notice of Grininke beymelekh, which incidentally was recently very

favorably reviewed in HaAretz by Benny Mer (HaAretz [24.3.06, p.

hey 1], or click here

for an online version).

2)----------------------------------------

Date: 27 March

2006

From: David Mazower

Subject: Artists' Portraits of Yiddish Writers, 2nd Series

Artists'

Portraits of Yiddish Writers

By

David Mazower

My previous article on the subject

of artists’ portraits of 20th-century Yiddish writers ended with an

invitation to readers to come forward with information about other similar

portraits. I am grateful to three

correspondents who did so.

Joseph Opatoshu’s grandson,

Dan Opatoshu, wrote with details of several portraits of his grandfather by

contemporary Jewish artists. They include “lifesize busts, woodcuts, ivory

carvings, Chagall pen and inks, and even satirical cartoons from the European

and American Yiddish press”.

The Yiddish literary scholar

Joseph Sherman, who is currently completing a biography of Dovid Bergelson, is

keen to trace a portrait of Bergelson mentioned in a memoir by the writer Rokhl

Korn. In an essay entitled “The Destruction of Yiddish Culture” she describes visiting

Bergelson in his home in Moscow during WW2 and being shown the portrait by

Bergelson himself. Its current

whereabouts are unknown.

And Zachary Baker mentioned a

portrait of the Montreal Yiddish poet Ida Maze by the artist Louis Muhlstock.

He also recalled the reading room of the old YIVO library on Fifth Avenue:

“There were a number of

artists’ portraits of Yiddish writers on the wall behind the circulation desk.

I am unable to recall exactly which ones hung there, though one in particular

really stood out: a self-portrait, in oil, by Moyshe Leyb Halpern. I believe

that there were portraits of Sholem Aleichem, H Leyvik and Jacob Glatstein as

well. There was a bas-relief of Peretz, which once prompted a perplexed Xerox

repairman of West Indian background to ask me why we had a sculpture of Stalin

hanging there.”

I hope to include

illustrations of some of these portraits in future articles in this series.

Mention of Moyshe Leyb

Halpern’s self-portrait also serves as a reminder of the large number of

artist-writers and writer-artists in the Yiddish literary world, the former

group being considerably more numerous than the latter.

The Yiddish-speaking artists

who contributed occasional art criticism, prose, poetry or memoirs to the

Yiddish press include: Yude Tofel, Isak Likhtnshteyn, Louis Lozovik, Boris

Aronson, Yonye Fayn, Yankl Adler, Uriel Birnbaum, Moyshe Oved, and, of course,

Mark Chagall. Another was Josef Herman, whose sketch of the Whitechapel Yiddish

poet Avrom-Nokhem Shtensl is included below.

Far fewer writers displayed anything like comparable artistic ability.

Apart from Moyshe Leyb Halpern, Moyshe Broderzon was an accomplished artist,

and Sutzkever was capable of some very good self-caricatures. Even rarer are

those who have made equally significant and talented contributions in both

spheres. Yonye Fayn, the Brooklyn-based artist and author born in Russia in

1914, who has defied his increasing infirmity and continued to produce

remarkable work with an intensity and vigor of a man half his age, is one

notable example. Another is that of Yosl

Kotler, the brilliant radical satirist, pupeteer, sketch-writer and

caricaturist. The prodigious talents of

Kotler and his partner Zuni Maud have yet to be properly documented. I have included some of Maud’s work in this

issue, but his remarkable artistic gifts and extraordinary range of caricature

portraits of modern Yiddish writers deserve a full gallery of their own in a

future edition.

Gallery:

Josef Herman (1911 - 2000)

Born in Warsaw in 1911, Herman

matured as an artist in Poland in the 1930s. He escaped via France to Britain,

and became perhaps the leading postwar representative of a continental

tradition in British art. Fluent in

several languages including Yiddish, Herman was a cosmopolitan humanist who

nonetheless maintained a lifelong attachment to Yiddish culture and Jewish

tradition. He is a masterful colorist,

whose dark, brooding oil paintings are light up by intense enamel-like flashes

of colour. He was also a prolific draughtsman who left behind a vast quantity

of sketches and notebooks when he died a few years ago.

Herman wrote regularly on art

for The Jewish Quarterly, a literary magazine edited by his friend and

fellow Polish-Jewish émigré, Jacob Sonntag. He was also closely involved with Yiddish

cultural groups in London, and especially with the Yiddish-speaking circle in

Whitechapel organised by the poet Avrom-Nokhem Shtensl (1897 - 1983). Born into

a distinguished rabbinical family in Poland, Shtensl achieved an international

reputation as a Yiddish poet in Weimar Germany, fled the Nazis and arrived in

London in the mid-1930s. Passionately devoted to the Yiddish language and his

beloved Whitechapel, he became a familiar figure in the East End as the editor,

leading contributor and chief salesman of the Yiddish literary magazine Loshn

un lebn (Language and Life).

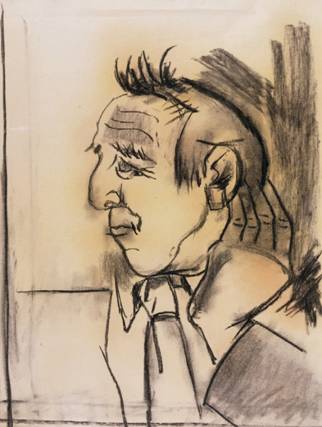

Herman’s sketch of Shtensl was

one of several he made in the 1940s, perhaps observed during one of the poet’s

regular shabes literarishe nokhmitogs, Saturday afternoon

literary gatherings often held in those days above a kosher café on the

Whitechapel Road.

Portrait sketch of Avrom-Nokhem Shtensl

By Josef Herman

(click here for higher resolution)

Charcoal and pencil on paper, 60 x 46.5 cm

c. 1946

Ben Uri Gallery - the London Museum of Jewish

Art

Zygmunt Menkes (1896 - 1986)

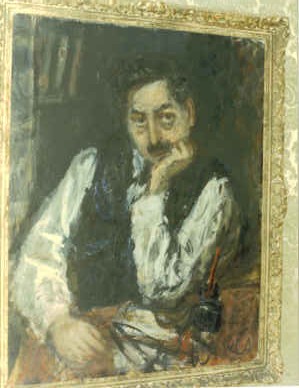

The artist Zigmunt Menkes and

the writer Sholem Ash were friends and compatriots whose lives followed similar

paths: both were born and grew up in Poland, lived in France in the 1920s and

30s, and spent their later years in the United States.

Menkes was born in present-day

Lviv (formerly Lvov/Lemberg) and studied art in Poland and then Berlin. He

settled in Paris in 1923, and became a leading member of the Montparnasse

colony of Jewish émigré artists, along with Eugene Zak, Raymond

Kanelba, Leopold Gottlieb, Leon Weissberg and many others. Menkes was one of the most lyrical colorists

of the School of Paris group and continued to paint his soulful, dark-hued

portraits, nudes, still-lives and paintings of Jewish religious life until well

into his eighties. In 1935 he left for

New York, and eventually settled in Riverdale, New York where he died in

1986.

Asch and Menkes both frequented

the same Paris hang-outs, notably cafes like La Rotonde and Le Dome. Asch owned one of Menkes’ finest Jewish subjects, a large

double portrait of a father and son enveloped in a prayer-shawl, which hangs to

this day in the study of the Asch house-museum in Bat Yam, Israel. This portrait, painted shortly after both men

had found refuge from Nazi-occupied Europe in the United States, was presumably

commissioned by Asch himself.

Portrait of Sholem Ash

by Zygmunt Menkes

Oil on canvas,

c 1940

Private

collection, UK

Henryk Berlewi (1894 - 1967)

Berlewi was born in Warsaw,

and spent his early years as an artist moving between Poland, France and

Germany. An important practitioner and

theorist of modern graphic and abstract art,

Berlewi was also a highly skilled draughtsman who sketched most of the

leading figures in Warsaw’s thriving Yiddish literary and cultural scene of the

1920s. He died in Paris in 1967.

Menakhem Kipnis was the

leading Jewish folklorist in interwar Poland. Popular and likeable, he was a

man of many parts: a scholar and professional ethnographer, an enthusiast for

Jewish popular culture and folkways, and a much-loved singer and performer.

Born in Volynia in the Ukraine in 1878, his childhood was spent as a travelling

synagogue chorister. From 1902 to 1918 he sang tenor in the chorus of the

Warsaw National Opera. At the same time he began to collect Yiddish folk songs

and stories and contribute articles to the Warsaw Yiddish press, writing on

cantorial music and folklore. Kipnis was also an accomplished professional

photographer whose studies of Polish Jewish life appeared in the Sunday sepia

supplements of the New York Yiddish Forverts from the late 1920s. Kipnis

died of a blood clot in the Warsaw ghetto in 1942; his enormous collection of

Jewish folklore materials was with him

to the end but was never recovered.

(For more on Berlewi’s varied artistic career, see the articles

by this author and Seth Wolitz in recent editions of The Mendele Review, TMR

vol. 9, no. 5 and TMR vol. 9, no. 6. For details of Kipnis’

remarkable life, I am indebted to Itzik Gottesman’s recent scholarly monograph Defining

the Yiddish Nation / The Jewish Folklorists of Poland, Detroit, Wayne State

University Press, 2003)

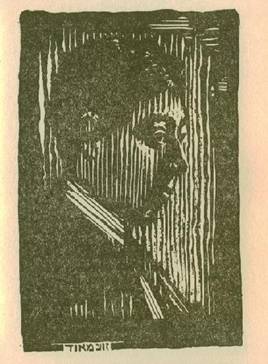

Portrait of Menakhem Kipnis

by Henryk Berlewi

Pencil on paper,

c1925

Private

collection, UK

Zuni Maud (1891 - 1956)

Maud was born in Vashilkov

near Grodno, Russia. He came to the United States in 1905 and studied art at

Cooper Union Institute and the National Academy of Design. Maud was soon making a name for himself as a

cartoonist for the New York Yiddish press (especially for satirical journals

like Der kibitser and Der

groyser kundes) and a prolific illustrator of Yiddish books. An artist of exceptional fluency and

versatility, Maud was equally at home working in oils, woodcut, charcoal or

ink. He was also a humorist who teamed

up with the equally gifted and versatile artist/writer Yosl Kotler (and Jack

Tworkov) to create an extraordinary Yiddish radical marionette theatre in

Manhattan in the 1920s.

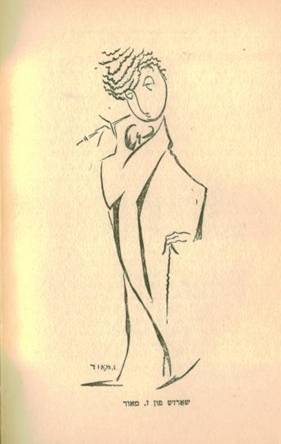

Moyshe Nadir (1885 - 1943) was

the darling of America’s Yiddish-speaking radical and Bohemian intelligentsia

following his conversion to the Communist cause. His dazzling irreverent verses, full of

nonsense words and witty rhymes - a sort of cross between Mayakovsky and the

Marx Brothers - ensured him a loyal and devoted readership. Maud illustrated an

early Nadir pamphlet of erotic verse (Vilde royzn / Wild Roses,

published in 1915) and contributed these sketches of Nadir to the celebratory

anthology published in 1926. Maud does a

superb job of capturing Nadir’s likeness - his mop of curly hair, sleepy eyes

and chubby cheeks - while also conveying his egocentric, capricious and

sarcastic personality.

4

portraits of Moyshe Nadir

by Zuni Maud

(reproduced in Noyekh Shtaynberg: A bukh

moyshe nadir, New York, Leben, 1926)

3)---------------------------------------------

Date:

From: Zelda Kahan Newman

Subject: The identity of two languages locked in embrace: Hebrew and Yiddish

The

identity of two languages locked in embrace:

Hebrew

and Yiddish

By

Zelda Kahan Newman

In recent years Paul Wexler

shocked many when he claimed that Yiddish is essentially a Slavic language

unrelated to Hebrew or German[i], and Ghil`ad Zuckermann got equal shock value from his claim that

what he calls “Israeli”[ii], and others call “Modern Hebrew” is not the language of Isaiah.[iii] I will contend here that

these claims rest for the most part on a similar straw man built up only so

that it can be knocked down with shock and awe. There is, however, a serious question that

their claims raise. It is an ontological

question that has vexed philosophers since Heraclites and one that we would do

well to consider. I will do my best to provide

an answer to this question and I invite others to consider the issue

seriously. Finally, my own research has

shown that some of the patterns of Yiddish are derived from the Hebrew-Aramaic

that the Jews who settled in Ashkenaz brought with them from the

Wexler claims that Yiddish

arose in a mixed Sorbian (Slavic)-Germanic environment. The speakers of Early Yiddish “relexified”

their language to High German early on (between the 9th and the 12th

centuries), and then (at least 300 years later), “relexified” their speech once

again to the Yiddish that Ashkenazic immigrants brought with them to their

area.[iv] This makes Yiddish, according

to Wexler, a Slavic language.[v]

If one were to agree with

Wexler that Yiddish is essentially a Slavic language (as Zuckermann appears to

do), and if one were to suppose that Yiddish is the sole component of the newly

revived Hebrew language, then one would

have to conclude that Hebrew is also a Slavic language. However, while Wexler makes this last claim,

Zuckermann does not. As Zuckermann sees

it, the revivers of Modern Hebrew, all native speakers of Yiddish themselves,

did in fact transfer the linguistic patterns of Yiddish to this new creation of

theirs. However, he claims that Yiddish

is only one of the contributors to Modern Hebrew. As he sees it, older forms of Hebrew as well

as Yiddish “act equally as primary contributors”[vi] to Modern Hebrew. He admits

that “while Israeli phonetics, phonology and syntax are European, its

morphology and basic vocabulary are mainly- albeit not exclusively- Semitic.”[vii]

For all that the claims of

Wexler and Zuckermann seem outlandish, a look at the finer print of their

writings shows that they set up a straw man only so that they can knock it down

with great fanfare. Wexler claims that

Yiddish is not genetically a Germanic language[viii] and Zuckermann claims that Modern Hebrew can not be “genetically

classified”[ix] as a Semitic language. But as

both know, and Zuckermann himself so aptly puts it, “the reality of linguistic genesis

is far more complex than a simple family tree allows.”[x] Even languages that are not

“engineered” (as Hebrew was) undergo non-genetic changes. Areas are invaded and conquered or over-run,

the conquerors, (or new immigrants), speakers of an alien language, lend new

elements to the over-run language. We

need only consider what the Norman Conquest did to English[xi]. Occasionally, interaction

between two very different languages is entirely peaceable. If the interacting languages are radically

different, the result of this inter-action is serious non-genetic change. This has occurred in the Carpathian region of

Hungary-Romania, where the meeting of a Romance language and a Finno-Ugric

language resulted in a new mixed language that incorporated features of both

languages.[xii]

Once we learn to look past the

red herring of genetic linkage, we will find a hidden agenda behind the claims

of both Wexler and Zuckermann. Both feel

there is a need to sever the link between ancient and Modern Hebrew. Wexler makes no attempt to keep his agenda

secret: “The explicit purpose of resurrecting “Old Hebrew” was to justify the

claim of most contemporary Jews to be descended from an earlier Palestinian

Jewish people and hence the sole [sic!] rightful heirs to

First to Wexler. Few thoughtful contemporary Jews would be

foolish enough to contend that all modern Jews are “descended from an earlier

Palestinian Jewish people”. Nor has the

claim been made that any living Ashkenazic Jew has had only forebears who can

be directly traced to

Zuckermann, who admits that

earlier versions of pre-Modern Hebrew contributed to Modern Hebrew, seems to

have an ontological problem. For him, if

there is no continuous chain of native speakers of Hebrew, and indeed there is

none, then later speakers of Hebrew can not be said to be speaking the same

language. Here we have hit that thorny

question first brought up by Heraclites and known to modern philosophy as

“Diachronous Identity”[xv].

Different

Stages of “the same” object

The problem simply put is:

when an object changes over time, in what sense can a later version of that

object be considered “the same as” (or “identical to”) the earlier version of

the object? Heraclites, of course, had a

simple answer: “You cannot step twice into the same river, for other waters and

yet others go ever flowing on.”[xvi] For him, there was no

identity over time. And yet humankind

has wanted to consider an object “the same” over time. How to do this?

Philosophers have attempted

all sorts of strategies to get at a satisfactory answer. Here I will consider only one approach, the one

that appeals the most to me. This

approach admits that there are different senses of identity. In the strict sense, later versions of a

changed object are not identical to the original object, but there is a loose

sense in which a later version of the object can be said to be identical to an

earlier version.[xvii] This is possible because the

object has different instantations at different moments in time. At any moment, the later, slightly changed,

object is understood to be part of the

same sequence as the instantation that preceded it and the instantation that

follows it. In this way, the earlier

members of the sequence are said to be loosely identical with the later members

of the sequence.

Wittgenstein's

family of resemblances

In his Philosophical

Investigations Wittgenstein addressed the question of what is common to

language activities or what makes the various activities into language or part

of language. This is not the same

question as we posed above.

Nevertheless, we do well to look at the approach Wittgenstein takes: his

insights are worthy of importation. If borrowed, they can shed light on our own

very vexing question. Here is what he

says about language activities:

“I am saying that these

phenomena have no one thing in common which makes us use the same word for all-

but that they are related [italics in the original] to one another in

many different ways. And it is because

of this relationship, or these relationships, that we call them all language.”[xviii] Further on he suggests that

we examine the disparate phenomena carefully.

“And the result of this examination is: we see a complicated network of

similarities overlapping and criss-crossing: sometimes overall similarities,

sometimes similarities of detail. I can

think of no better expression to characterize these familiarities than `family

resemblances’; for the various resemblances between members of a family: build,

features, colour of eyes, gait, temperament, etc., overlap and criss-cross in

the same way.”[xix]

If we substitute different

stages of a language for Wittgenstein's different language activities and use

Wittgenstein's insight about looking for family resemblances, we come up with

the following formula for different stages of “the same” language: in order for

different instances of language to be considered “the same” language, there

must be family resemblances, common crucial elements of language that hold up

over time. And what might these elements

be?

The

Hebrew alphabet

For any Jewish language (and

most especially for Hebrew, the Jewish language), the foremost element

would have to be the use of the Hebrew alphabet for the written language. After all, it is the Hebrew alphabet that

ties Jews to their cultural heritage.

As for the other elements, the

answer is by no means obvious. I would

like to call on all who think deeply on this issue to give the best answer they

can to the question I have posed here. I

have suggestions of my own, but I will be happy to amend them or to entertain

other , better suggestions.

Core

lexical items

In the twentieth century,

linguists developed a system of measuring the differences and historical

distance between two corpora of language.[xx] They took a core of basic

vocabulary items consisting of items like body parts, numerals, terms for

social relations and geological features and compared the two corpora to see

how different they were. The assumption

was that these core lexical items are less subject to change than other parts

of a language. Similarities within this basic core of lexical items was said to

be a good indication of a genetic relationship.[xxi]

This concept of a core of

crucial lexical items can be used as an

indicator of Jewish Diaspora languages.

Any Jewish Diaspora language must have a core of lexical items for concepts

that are uniquely Jewish. A Jewish

language without terms either for bris/brit or mila is

unthinkable. Indispensable, too, are

lexical items like t(e)filin, mezuza, matsa, and tora. Jewish identity is deeply bound up with these

terms and there is no way a Jewish language can get by without them. It is no surprise that we find Hebrew-derived

words for all these terms in Yiddish. We

have every reason to expect them in every and any other Jewish Diaspora

language in the world.

The core of lexical items for

the Hebrew language itself is a different matter entirely. If Hebrew is to be used not as the second or

third language of a community, but as its first language, then we would expect

the core lexical items to be just those

that are candidates for the core corpus of any human language. Terms for social relations (like man and

woman, father and mother), terms for food and drink, and for numerals and

geographical features are just those that we test for. And these very terms are the ones that have

remained in the vocabulary of Hebrew all these thousands of years. Speakers of Modern Hebrew (the very speakers

that Zuckermann insists on calling speakers of “Israeli”) use the very same

terms for these concepts as did speakers of Biblical Hebrew. That alone should be enough of a similarity

to make us feel that we are speaking of “the same” language.

Intonation

If the Hebrew language and the

concept of a stable corpus of crucial lexical items run both across Jewish

languages (where the core items focus on specifically Jewish items) and within

varieties of Hebrew (where core items focus on the basics of all human

culture), a specifically Jewish intonation is a cross-pollinating

phenomenon. It is a feature that began

with pre-Diaspora Hebrew and Aramaic.

It was carried over to Ashkenazic Yiddish, and it has traveled from

there back to Modern Israeli Hebrew.

This is not the place to

recapitulate in full my argument for the origins of modern Yiddish

intonation. Briefly put, I have

suggested that some of the intonation patterns of modern Yiddish entered the

language via the Talmudic chant brought to Ashkenaz by exiles from the

A second paper I have written,

this one on the language of one of Aharon Appelfeld's books, finds these very

same (now) Yiddish intonation patterns in the

language of a modern Hebrew author.[xxiii] It is not as though Appelfeld

consciously used these patterns. The

fact is, though, that there is no way to understand the language of his book

without assuming that Yiddish intonation lurks in the background.

The only Jewish Diaspora

language of which I have some knowledge is Yiddish. It is tantalizing to suppose that other

Jewish languages also have intonational elements that are derived from their

community's Talmudic chant pattern. It

is for others with a knowledge of other Jewish languages to pose this question

and look for this connection.

Conclusion

Once we realize that Wexler's

and Zuckermann's shocking claims are based on the false assumption that the

only possible identity between languages is genetic identity, we are left

asking ourselves what it is that gives languages identity over time. We have argued for a “loose identity” that

looks for “family resemblances” between different versions of Hebrew and

different Jewish languages.

I have posited three features

of a Jewish language. The first, which

travels vertically in time, is a core of stable lexical (culturally Jewish)

items. The second, use of the Hebrew

alphabet can (and does) move horizontally across languages. The third, intonation patterns, have shown

that they can (and do) travel in a loop: the ones I know began as features of

Hebrew-Aramaic. They were transferred to

Yiddish, and after centuries of lodging in this Diaspora Jewish language, they

have been “repatriated” to Hebrew, the primary Jewish language. Are these the only features that “identify” a

Jewish language? It is likely that there

are others. I invite others to help find

them.

Lehman College, CUNY

[i] Paul

Wexler, Two-tiered Relexification in Yiddish: Jews, Sorbs, Khazars and the

Kiev-Polessian dialect, (Berlin and New York, 2002)

[ii] Ghil`ad

Zuckermann, “Mosaic or mosaic? The Genesis of the Israeli Language”, www.zuckermann.org/mosaic.html,

p.1

[iii] He claims

that Israelis can understand Isaiah only because “they study the Old Testament

at school for eleven years.” p.3

[iv] Wexler,

pp.1-2. The rest of his book is a

clarification and justification of the claim he makes early on in the book.

[v] See fn

IV. In particular, Wexler claims his

hypothesis predicts that Yiddish “exhibits no (or few) German grammatical

features that violate Slavic grammar”. p.13

[vi]

Zuckermann, p.1

[vii]

Zuckermann, p.3

[viii] This is

the essence of Wexler's argument throughout his book.

[ix] See

Zuckermann, p.1

[x] Zuckermann

himself admits that the family tree (Stammbaum) model does not do justice to

the “complex genesis of Israeli”, p.7

[xi] These

facts are (obviously) known to Zuckermann.

What distinguishes Hebrew from these other cases is that the other

languages have had a continuous written and spoken language, while only written

Hebrew has had a continuous history.

[xii] Personal

communication. I had students from this mixed area who spoke

this mixed language as well as varieties of (more or less) Standard versions of

each of the other languages.

[xiii] Wexler,

p.41

[xiv]

Zuckermann, p.3 Zuckermann uses the term “Old Testament” where I would

prefer "Hebrew Scriptures."

[xv] For a

serious explanation of this issue see “Diachronous Identity Puzzles” ,

http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/identity-time

[xvi] See no. 12

of the Fragments, Heraclites,

http://ratmachines.com/philosophy/heraclites

[xvii] See Chisholm,

R., “The Loose and Popular and the

Strict and Philosophical Senses of Identity” in Care, N and Grimm, H. Perception

and Identity, (Cleveland, 1969), pp.82-106.

[xviii] Ludwig

Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations, translated by G.E. Anscombe,

(Oxford, 1977), p.31e

[xix]

Wittgenstein, p.32e

[xx] This

method is called lexico-statistics.

See Sarah C. Gudschinsky,“The

ABCs of Lexico-statistics”, in Language in Culture and Society,

Dell Hymens, ed. (New York, 1964), pp.612-623.

[xxi] See fn

xx. Both Wexler and Zuckermann are

(obviously) familiar with this method.

Both feel it is not to be used for the case they examine. Although I think Zuckermann is quite right to

speak of the complex genesis of Hebrew, I believe he underestimates the

importance of this core vocabulary.

[xxii] Zelda

Kahan Newman, “The Jewish Sound of Speech: Talmudic Chant, Yiddish Intonation

and the Origins of Early Ashkenaz” in The Jewish Quarterly Review, XC,

nos. 3-4 (January-April, 2000), pp.293-336.

[xxiii] Zelda

Kahan Newman, “Yiddish Haunts: the Yiddish Underpinnings of Appelfeld's Laylah

Ve-od Laylah” in Mikan, Journal for Hebrew Literary Studies: the

World of Aharon Appelfeld, vol.5 (Beer Sheva, January 2005), pp.81-90.

4)---------------------------------------------------------

Date: 27 March 2006

From: Amitai HaLevi

Subject: A Reply to Ghil'ad Zuckermann

re. "Israeli"

Dear Editor of The Mendele Review,

In maintaining that

"Modern Israeli Hebrew is only very partially a direct descendent of

Biblical Hebrew," Ghil'ad Zuckermann does violence to the term "descendent". "Descendent" is not

synonymous with "clone". Languages, like people, are the

direct descendents of more than one ancestor.

Itzhak Laor's argument that "the Israeli highschool graduate cannot

deal with a chapter of Tanakh that he

has not studied beforehand without a Biblical Hebrew dictionary" (true of,

say, the Book of Job but hardly

of Genesis or Samuel) is evidence that."the Tanakh is

written in a foreign language", makes no more sense that saying that the

fact the American highschool

graduate cannot deal with the Canterbury Tales without a

glossary, proves that Chaucer wrote in a foreign language.

If what Zuckermann and Laor

(whose political agenda is not irrelevant to the issue in question) are really

saying is that Modern Israeli Hebrew is not "identical" with Biblical

Hebrew, they are breaking through an open door. Secular Hebrew literature of

the Enlightenment (Mapu, Smolenskin, Sh. L. Gordon, etc. was indeed written in

Biblical Hebrew, but the language was

enriched with Mishnaic Hebrew -- replete with Aramaic and Greek elements -- by

Bialik and his contemporaries a century ago. The language of Modern Hebrew

literature drew heavily (principally via

Agnon), on Rabbinic Hebrew as well. Nor should we ignore the infusion of Arabic and Spanish features,

derived from the literature of the Golden Age in Spain.

The spoken language is, of

course peppered with Yiddish, Russian, French, Arabic, Ladino, etc. Children

call their parents "abba" and "ima" (Aramaic), enjoy eating

"shnitsl (German) ve-tshipsim (English with a superfluous Hebrew plural),

or perhaps "uevos `haminados" (Ladino), but most characteristically

"falafel" and "`houmos" (Arabic). Incidentally, there are

two classical ways "lenagev" (to wipe, Biblical) houmos with

"pitta" (Arabic): with a "vish" or a with a

"dukh" (corruption of "durkh"). Not Biblical Hebrew

to be sure, but Hebrew nonetheless.

Finally, while the teaching of

Tanakh can and should be improved, Israeli teen-agers relate to the lyrics

of love songs like "yonati be hagvei hasela" (Song of Songs 2:14) and

"el ginat egoz" (Song of Songs 6:11) quite well.

Amitai Halevi

Dr. E.A. Halevi, Professor

Emeritus

Department of Chemistry Technion - Israel Institute of Technology, Haifa

32000, Israel

5)--------------------------------------------------------

Date: 27 March 2006

From: Jan Hovers and ed.

Subject: Sophie Tucker Remembered

a. A general description of

Sophie Tucker's life

Please visit http://www.jwa.org/discover/comedy/tucker.html

b. "Mayn yidishe mame" in Yiddish by Sophie Tucker, 1928 – audio

file (Jan Hovers)

Follow http://www.78rpm.hovers.nl/tuckerB.wax

c. Yiddish text of "Mayn yidishe mame"

(ed.)

„îÖÇï ééÄãéùò îàÇîò“ [èò÷ñè ÷àÈøéâéøè ôÏåï ÷åìèåø-÷àÈðâøòñ 28/3/06]

[âòæåðâòï ôÏåï ñàÈôÏé èàÈ÷òø àéï 1928 àéï ìàÈðãàÈï]

1. Ôé àéê ùèÖ ãå [ãàÈ] àåï èøàÇëè

2. ÷éîè [÷åîè] îéê ôÏàÈø îÖÇï àÇìèò îàÇîò.

3. ðéùè ÷Öï àÈôÌâòôÌàÇ÷èò éòð÷ò

4. àåï ðéùè ÷Öï àÕñâòôÌåöèò ãàÇîò,

5. ðàÈø àÇ îåèòø ôÏåï ôÏòøöÖÇèï [ôÏàø öÖÇèï],

6. ôÏéï [ôÏåï] âøÕñ öøåú àÖÇðâòáÕâï,

7. îéè àÇ ëÌùøä ééÄãéùò äàÇøõ

8. àåï îéè ôÏéì ôÏàÇøÔÖðèò àÕâï.

9. àéï ãé æòìáò ÷ìÖðò øåî÷òñ [öéîòøï]

10. Ôé æé àéæ àÇìè àåï âøåé [âøàÈ] âòÔàÈøï

11. æéöè æé àåï ðÖè àåï çìåîè

12. ôÏéï [ôÏåï] ãé ìàÇðâ-ôÏàÇøâàÇðâòðò éàÈøï

13. Ôòï ãé äÕæ àéæ ôÏåì âòÔòæï

14. îéè ãòí ÷ìàÇðâ ôÏåï ÷éðãòø ùèéîòñ;

15. àéðòí ÷éèùï [÷éê] äàÈè âòùîò÷è

16.ãòø ùáú ÷éâì [÷åâì] îéèï öéîòñ.

17. àéø îòâè îéø âìÖáï àÇæ áÖÇ àéðãæ [àåðãæ]

18. äàÈè ðéè âòôÏòìè ãòø ãìåú;

19. àÈáòø ãàÈê ôÏàÇø àéðãæ [àåðãæ] ãé ÷éðãòø

20. äàÈè âò÷ìò÷è àÕó àÇìòñ.

21. ãàÈñ ùèé÷ì áøÕè ôÏéï [ôÏåï] îÕì

22. ôÏìòâ æé àéðãæ [àåðãæ] ôÏøÖÇÔéìé÷ âòáï,

23. àåï ôÏàÇø àéøò ÷éðãòø ÔàÈìè æé ãàÈê àÇÔò÷âòìÖâè ãòí ìòáï.

24. àÇìÖï âòøàÈîè, àÇìÖï âòðÖè, àÇìÖï âòÔàÇùï àåï âòáéâìè,

25. âòàÇøáòè áÖÇ èàÈâ, âòàÇøáòè áÖÇ ðàÇëè

26. àåï àéîòø [ùèòðãé÷] àÇ ÷éðã âòÔéâìè.

27. àåï àÈè ãàÈñ äÖñè àÇ ééÄãéùò îàÇîò.

28. àåï Ôé âìé÷ìòê æÖÇè àéø îòðèùï

29. ÔàÈñ àéø äàÈè ðàÈê àÖÇòøò îàÇîòñ,

30. ãòí àÖáòøùèï ãàÇøôÏè àéø áòðèùï

31. àåï îéè àéø ùÖèì ùòîè æàÇê [æéê] ðéè

32. àåï äàÇìè àéø ðéè ôÏàÇøäàÇìèï.

33. àéø ãàÇøôÏè àéø ÷éùï [÷åùï] àéøò äòðè

34. àåï àéø àÇæÕ èÖÇòø äàÇìèï;

35. àéø áøÕëè áÖèï [áòèï] âàÈè

36. ôÏàÇø àéø âòæéðè [âòæåðè] àåï ôÏàÇø àéø ìÖáï [ìòáï].

37. ôÏåï àÇìòñ âåèñ àåï øàÇë÷Öè [øÖÇë÷Öè]

38. ÷òï òø àÖÇê àÇ ôÏåìò âòáï,

39. îéìéàÈðòï èàÇìòø, ãÖÇàÇîàÇðèï [áøéìéàÇðèï], äÖÇæòø âøÕñò, ùÖðò,

40. àÈáòø àÖï æàÇê àÇó [âòùøéáï: àåéó] ãòø Ôòìè ãàÈñ âéè àÖÇê âàÈè ðéùè îòø Ôé

àÖðò,

41. àÇ ééÄãéùò îàÇîò, æé îàÇëè ãàÈê æéñ ãé âàÇðöò Ôòìè,

42. àÇ ééÄãéùò îàÇîò, àÕ Ôé áéèòø Ôòï æé ôÏòìè.

43. àéø ãàÇøôÏè ãàÈê ãàÇð÷òï âàÈè, ÔàÈñ àéø äàÈè àéø ðàÈê áÖÇ æéê.

44. àéø ÔÖñè ðéè Ôé èøÕòøé÷ ñ'Ôòøè

45. Ôòï æé âÖè àÇÔò÷ öå âéê.

46. àéï ÔàÇñòø àåï ôÏÖÇòø

47. ÔàÈìè æé âòìàÈôÏï ôÏàÇø àéø ÷éðã.

48. ðéùè äàÇìèï àéø èÖÇòø,

49. ãàÈñ àéæ âòÔéñ ãé âøòñèò æéðã;

50. àÕ, Ôé âìé÷ìòê àåï øÖÇê àéæ ãòø îòðèù

51. ÔàÈñ äàÈè àÇæàÇ ùÖðò îúÌðä âòùòð÷è ôÏéï [ôÏåï] âàÈè,

52. ðåø [ðàÈø] àÇï àÇìèéèù÷ò ééÄãéùò îàÇîò, îàÇîò îÖÇï!

d. Romanized text of "Mayn yidishe mame" (ed.)

Mayn

yidishe mame [transcription corrected

28.3.06 by Kultur-kongres]

as

sung by Sophie Tucker in 1928 in

1. vi ikh shtey du [do] un trakht

2. kimt [kumt] mikh for mayn alte mame.

3. nisht keyn opgepakte yenke

4. un nisht keyn oysgeputste dame,

5. nor a muter fun fertsaytn

6. fin [fun] groys tsures [tsores] ayngeboygn,

7. mit a kushere [koshere] yidishe harts

8. un mit fil-farveynte oygn.

9. in di zelbe kleyne rumkes

[tsimern]

10. vi zi iz alt un gru [gro] gevorn

11. zitst zi un neyt un kholemt

12. fin [fun] di lang-fargangene

yorn

13. ven di hoyz iz ful

gevezn

14. mit dem klang fun kinder shtimes,

15. inem kitshn [kikh] hot geshmekt

16. der shabes kigl [kugl] mitn

tsimes

17. ir megt mir gleybn az

bay indz [undz]

18. hot nit gefelt der

dales

19. ober dokh far indz [undz] di

kinder

20. hot geklekt oyf ales

21. dos shtikl broyt fin moyl

22. fleg zi indz [undz] frayvilik

gebn

23. un far ire kinder volt zi dokh

avekgeleygt dem lebn.

24. aleyn geromt, aleyn geneyt, aleyn

gevashn un gebiglt,

25. gearbet bay tog, gearbet

bay nakht

26. un imer [shtendik] a

kind geviglt,

27. un ot dos heyst a yidishe mame.

28. un vi gliklekh zayt ir mentshn

29. vos ir hot nokh ayere mames,

30. dem eybershtn darft ir bentshn.

31. un mit ir sheytl shemt zakh

[zikh] nit

32. un halt ir nit farhaltn.

33. ir darft ir kishn ire hent

34. un ir azoy tayer haltn,

35. ir broykht beytn [betn] got

36. far ir gezint [gezunt] un far ir leybn [lebn].

37. fun ales guts un rakhkayt[raykhkeyt]

38. ken er aykh a fule gebn,

39. milyonen taler, dayamantn [brilyantn], hayzer groyse, sheyne,

40. ober eyn zakh af der

velt dos git aykh got nisht mer vi eyne

[CHORUS]

41. a yidishe mame,

zi makht dokh zis di

gantse velt;

42. a yidishe mame, azoy vi biter ven zi felt.

43. ir darft dokh danken

got, vos ir hot ir nokh bay zikh.

44. ir veyst nit vi troyerik s'vert

45. ven zi geyt avek tsu gikh.

46. in vaser un fayer

47. volt zi gelofn far ir kind.

48. nisht haltn ir tayer,

49. dos iz gevis di greste zind;

50. oy, vi gliklekh un raykh iz der mentsh

51. vos hot aza sheyne metone geshenkt fin [fun] got,

52. nur [nor] an altitshke yidishe mame, mame mayn!

e. "Mayn yidishe mame" in English by Sophie Tucker, 1928 – audio

file (Jan Hovers)

f. Sophie Tucker's 1928 Dutch "Mayn

yidishe mame" record illustrated (Jan Hovers)

g. Leo Fuld's Dutch record of "Mayn

yidishe mame" illustrated (Jan Hovers)

6)--------------------------------------------------------

Date: 27 March 2006

Subject: Adina Bar-El's Grininke beymelekh – a further notice (ed.)

We repeat the announcement of

this new book to include a useful telephone number accidentally omitted from TMR 10.02.

Adina Bar-El. Beyn haEytsim haYerakrakim; Itoney

yeladim beYidish uVeIvrit bePolin 1918-1939. Jerusalem: Dov Sadan Institute [Hebrew

University] / Zionist Library [World Zionist Organization], 2006, 519+XXX pp.

[ISBN 965-440-055-3]. 1st 100 copies in Israel will cost 60 shekels

postpaid [check to Yechiel Szeintuch (Makhon Dov Sadan), Dept. of Yiddish,

Hebrew University, Mt. Scopus, Jerusalem, Israel. (Messages may be left 24

hours a day at (972) (2) 588-3527)]. Overseas orders to Adina Bar-El,

Moshav Nir-Yisrael, Israel [Tel-Fax 972-8-6729354]. [English title: Under

the Little Green Trees; Yiddish and Hebrew Children's Periodicals in Poland

1918-1939; Yiddish title: Grininke beymelekh)].

---------------------------------------------------------

End

of The Mendele Review Vol. 10.03

Editor,

Leonard Prager

Subscribers to Mendele (see

below) automatically receive The Mendele Review.

Send "to subscribe"

or change-of-status messages to: listproc@lists.yale.edu

a. For a temporary

stop: set mendele mail postpone

b. To resume delivery: set mendele

mail ack

c. To subscribe: sub mendele

first_name last_name

d. To unsubscribe kholile: unsub

mendele

****Getting

back issues****

The

Mendele Review archives can be reached

at: http://yiddish.haifa.ac.il/tmr/tmr.htm

Yiddish

Theatre Forum archives can be reached at: http://yiddish.haifa.ac.il/tmr/ytf/ytf.htm

***