The

Mendele Review: Yiddish Literature and Language

(A

Companion to MENDELE)

-----------------------------------------------------------------

Contents of

Vol. 09.006 [Sequential No. 158]

Date:

1) In this

issue of TMR (ed.)

2) Some Comments on David Mazower's article on Henryk Berlewi (Seth L. Wolitz)

3) A Small Berlewi Gallery (Seth L. Wolitz)

4) Quotations from Mechano-faktura (Henryk Berlewi)

5) Coming issue: Menke

6) Coming book reviews

1)--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Date:

From: Leonard Prager

Subject: In this issue of TMR

In this issue

of TMR, Seth L. Wolitz -- a scholar of Yiddish literature and a longtime

student of Henryk Berlewi -- takes the floor to respond to David Mazower's

article on Henryk Berlewi in the last TMR (vol. 9,

no. 5). Freely assisted by the world wide web, Professor Wolitz adds to his

lively and challenging comments a small gallery of the artist's work, including

some of his best known and truly remarkable abstractions. We need to thank both

Mazower and Wolitz for working towards reestablishing the connection between

modernist Yiddish literature and Eastern European Jewish graphic art.

2)-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Date:

From: Seth L. Wolitz

Subject: Some Comments on David Mazower's article on Henryk Berlewi

Some

Comments on David Mazower's article on Henryk Berlewi

by

Seth L. Wolitz

I very much

appreciated David Mazower's communication (in TMR vol.

9, no. 5) on Henryk Berlewi, whose accomplishment I uncovered over thirty years

ago and on whom I have through the years published a number of essays. I would

insist on his importance not only as an illustrator and artist of Yiddish

poetry-covers but as an artist central to the entire avant-garde abstract art

movement in

"Between

Folk and Freedom: The Failure of the

Yiddish Modernist Movement in

"The

Jewish National Art Renaissance in

"Modernism in der Yidisher Literatur." Yidishe Kultur, No. 2

(March-April 1980), pp. 36-45. Reprinted

(without permission) in Folks-Sztyme,

"The

Khalyastre (1918-1925): A Modernist

Movement in

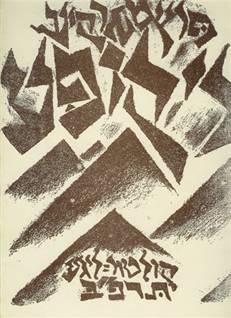

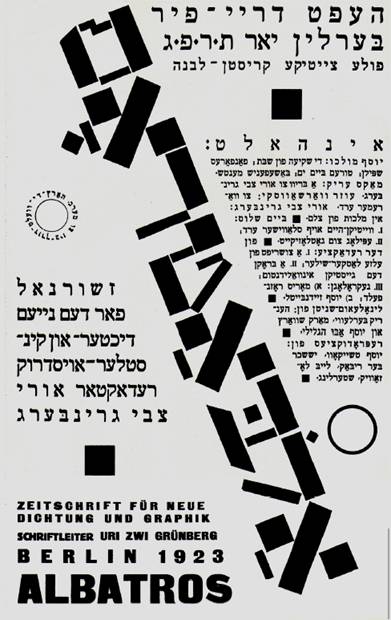

Berlewi's

masterpiece in terms of Yiddish culture is the

No. 3 (1923) cover of Albatros which he created for Uri-Tsvi

Grinberg when they were both in

Fig. 1

Berlewi was well known by 1920 as a brilliant young

plastic artist very much involved (like other young Eastern European Jewish

artists such as El Lissitzky and Tchaikov, etc) in seeking to define or

construct a distinct Jewish art or at least a Style beside Jewish themes or

images. Chagall's art was the starting

point of this thinking, albeit Chagall never liked to theorize Jewish art or

believed in it as something that could be sui generis. Still he encouraged in

his days at Vitebsk the pursuit of such a possibility. El Lissitzky was his

prized student who did remarkable work in attempting to create a Jewish style

[see Sikhes Kholin, Khad Gad Ya , two of his early but remarkable efforts] but

by 1919 El Lissitzky had given up on finding a Jewish Style and overwhelmed by

Malevich's Supremicist art and cosmic vision passed into complete abstraction

with his Prouns.

El Lissitzky arrived

in 1921 in Warsaw on the way to set up a Soviet exhibition of art in Berlin and

overwhelmed Berlewi by his abstract constructivist art and conceptions. Berlewi abandoned further efforts at finding

a Jewish style, having passed in two

years through neo-Romanticism,

expressionism and formism to now become a constructivist. Unlike El

Lissitzky who on commission did a Yiddish cover now and then until 1924 (and

contrary to Soviet critics never did abandon Jewish interests but found it wise

to be discreet!), Berlewi passed easily from Yiddish cultural circles to Polish

ones and in Berlin met all the major new artists who make up what we call today

the first abstractionists, Van Doesburg,

Moholy Nagy, and all the German Dadaists. As El Lissitzky pursued his star with

such brilliant works and new page designs, Berlewi in fact did the same and was

recognized by Herwarth Walden, the leading avant-garde art dealer and gallery

owner who published in his Der Sturm Berlewi's masterful Manifesto: Mechano-Faktura.

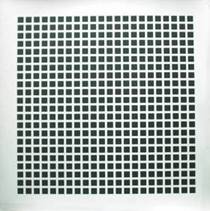

Fig. 2

Composition in Red, Black and

White (1924)

This work was

the most important expression of the new intention of producing art on

mechanical principles and removing the presence of the artist's hand. Berlewi

insists on the reality and acceptance of two-dimensionality in art and not the

artifice of creating a third dimension. Art was now in service to mankind, not

seeking to create beauty but to serve the needs of mankind. He accompanied this

manifesto with twelve designs of pure abstraction made of crisscrossing lines

and series of dots which today are recognized as the precursor of op art and

concrete art.

Berlewi

returned to Poland where he continued his experiments in constructivism and

formed an advertising agency as his name and fame grew. His one-man show

caused a sensation in Warsaw in 1924

when he held it in a automobile showroom with the cars all around. Here was

modernism fusing art and the pragmatic, the machine age in all its abstract

glory. At the same time he was a leading member of the Polish abstract artist's

constructivist group, BLOK, in which he wrote in Polish and took part in their

activities. At the same time he was active with the Yiddish Khalyastre

and did those splendid covers of Perets Markish's verse collection, Di Kupe

and Radyo, etc. as well as a cover for a

Hebrew volume, Legion.

Berlewi played

such a major role in constructivism and

functioned so comfortably with the Polish abstract artists, such as

Strzeminski, Kobro and Stazewski that he is always treated as Polish and his

Jewish side is downplayed as with El Lissitzky as "his early period."

No Polish publication ever leaves his name out as central to Polish abstract

art of the inter-war years. The Warsaw Jewish world took pride in his

accomplishment and he continued to write theoretical articles and critical ones

which were published in Ringen and other Yiddish journals and he never

stopped publishing in Yiddish even when he moved to Paris.

He moved in

Paris in 1928 for one good reason: he needed to keep body and soul together. He

was following what other Polish and Jewish artists were doing. Neither the

Polish abstract artists nor Berlewi could really sell much of their abstract

art. They made a little money with advertising but not enough. Poles did not

buy abstract art and as Chagall complains bitterly in almost every letter he

writes, Jews don't buy art. (It seems unreal given the vast Jewish collections

of today!) But neither Jews in Poland or anywhere else bought Abstract

art. So Berlewi moved to Paris and discovered

the bitter truth there that the French had no interest in pure abstraction

either. So he turned back to portrait painting.

Where was he

during the War? He seems to have escaped with his Mother to Southern France.

Who hid him and why remain a mystery. After World War 2 he returned to Paris

and eked out a living still doing portraits. Suddenly in 1958, the French

artist and critic Michel Seuphor tracked him down for a retrospect exhibit of

the first abstract artists of post-World War 1 and Berlewi returned to his

mechano-faktura abstractions. He reproduced some of his early abstract art and

continued to create new abstractions. One-man shows were given to him in Paris,

Berlin Warsaw, London and New York. The Germans and the English recognized in

his constructivist works the master of modern typographic design. He has been

written up by Neue Graphik and Typographica for his essential

contribution to page design and typography . In Europe his art is collected,

especially his abstractions.

The recent

auction of his figurative drawings to which David Mazower alluded does not do

credit to the importance of Berlewi. His figurative art is inferior to his real

accomplishment which is abstraction and typography. I have been collecting material on him for 20

years but so much has been destroyed. I

am writing a monograph now on Berlewi which will reveal that this artist was

one of Jewry's greatest artists of the 20th century. Only Chagall and El

Lissitzky are his possible superiors if such silly conceptions still hold sway.

He managed to live the life of an artist who was comfortable both as a Jew and

a universal man.

Alas the Poles

and Western art historians who do esteem

him greatly trundle him off into their world and obfuscate his Jewish concerns

and interests and accomplishments. On the other hand, the Yiddish establishment

has not forgotten him, but is too weak to make any efforts on his behalf. As to

the general Jewish world, Israel, and the Diaspora, he is totally forgotten or

considered like all the Jewish-born artists who do not paint Rabbis or water

carriers as another Akher, a delinquent who left us for Goyish territories and

fame. Berlewi deserves to be recognized

for what the secular Yiddish culture sought to accomplish in Eastern

Europe: create Jewish men and women, artists, etc. who were comfortable with

being both Jews and part of the modern world. It has been unfortunately the

Jewish scholars of Yiddish and Hebrew cultures in our own time who have let

slip by so many Jewish artists -- witness Philip Roth not listed among the key

Jewish writers in a recent listing! -- because they did not conform to more

parochial thinking of too many obscurantist or ideological Jewish academics.

We must thank

David Mazower for having taken notice of Berlewi and having recognized his

figurative art efforts. I hope these further few words invite TMR readers to

seek out the really great artistic accomplishment of Berlewi in his

abstractions. If one should wish to see some of them and the famous automobile

show, the best work in English that places him in his rightful place in

Eastern- European avant-garde art, see:

S.A. Mansbach: Modern Art in Eastern Europe from the Baltic to the

Balkans ca. 1890-1939, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999, pages

124-127.

3)-----------------------------------------------------

Date:

From: Seth L. Wolitz

Subject: A Small Berlewi Gallery

A

Small Berlewi Gallery

|

fig 3 |

fig 4 |

Two

compositions from the series Twelve Mechano-Faktura Elements 1924

|

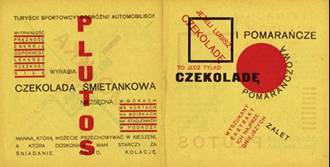

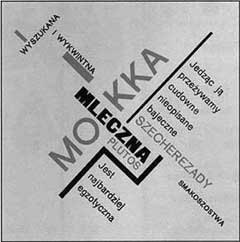

Fig 5 Portrait 1938 |

Fig 6 Plutos chocolate advertisement 1926 |

|

Fig. 7 Plutos advertisement applying mechano- |

|

Fig 8 Berlewi's cover for Perets Markish's Di kupe

( ["The

design is spectacular and purely expressionistic … abstract triangles rising

… form like fire the Hebrew letters of Di Kupe in fierce triangular

forms…" – SLW] |

4)--------------------------------------------------------------------

Date:

From: Seth L. Wolitz

Subject: Quotations from Mechano-faktura (Henryk Berlewi)

A selection of

quotes from Mechano-faktura, one of the first purely theoretical

manifestoes regarding abstract plastic art and esthetics by a Jewish artist.

From Mechano-faktura ( Der Sturm, Berlin, September,1924)

By texture is

meant: 1. The surface of the painted

canvas itself. 2. The intensity of and

density of the color, which depends on the physical character of the paint, the

so-called patina. In short, everything that makes up the material side of

painting.

Only after the

great upheaval in the fine arts (expressionism, cubism, futurism) have the

tremendous possibilities inherent in texture become apparent.

Painting,

thanks to texture, has come closer to its original function. However, in the

process, it has lost one of its specific characteristics, two-dimensionality.

If flatness is

considered intrinsic to painting, any three-dimensional (perspectival)

illusionism, as well as any actual plasticity, must be regarded as

inappropriate and as a violation of the true nature of painting.

If suitable

equivalents are found for materials like glass, sand, wood, we will be able to

achieve textual effects that are identical with the immediate effect of the

texture of the original material.

By consistently

pursuing and developing this principle of material equivalents, I created a new

and autonomous texture, which is independent of materials, and at the same

time, compatible with the two-dimensional nature of painting.

The aims of art

today can be defined as follows: a complete break with any imitation of

objects, autonomy of form; order; schematization; geometrization; precision (

to permit easy classification of the impressions received from the work). The

old technique of painting is not up to this task. It is even less use in the

creation of a new schematic textural system. In order to attain this end,

mechanical technology derived from industrial methods (which are free of the

whims of the individual and are founded on the exact mechanical function of the

machine) must be employed. Modern painting, modern art, must therefore, be

based upon the principles of machine production. An entirely new creative

system will be established with the help of the mechanization of texture and

the means of pictorial expression.... Through mechanization of the means of

painting, there will be a greater creative freedom and the possibilities of

invention will be increased.

(translated

by Katerine J. Michaelsen)

5)--------------------------------------------------------------

Date: 1 May 2005

From: ed.

Subject: Coming

issue: Menke

A coming issue

of TMR will be devoted to a compendious volume of Menke Katz's Yiddish

verse translated into English by the celebrated translator-team Barbara and

Benjamin Harshav. Menke. The Complete Yiddish Poems. Edited

by Dovid Katz and Harry Smith.

Maps by Giedre Beconyte. Published

by The Smith: New York 2005, 914 pp.

For ordering information: artsend@sover.net.

6)--------------------------------------------------------------

Date: 1 May 2005

From: ed.

Subject: Coming Book Reviews

Dovid Katz's Lithuanian

Jewish Culture (Vilna: Baltos Lankos, 2004, 398 pp), will yet be reviewed

in TMR, as will be Nancy Sinkoff's Out of the Shtetl (

Also scheduled

for review is John Myhill's Language

in Jewish Society: Towards a New Understanding. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters, 2004

------------------------------------------------------------------

End of The Mendele Review Vol. 09.06

Editor,

Leonard Prager

Subscribers to Mendele

(see below) automatically receive The Mendele Review and Yiddish Theater Forum.

Send "to

subscribe" or change-of-status messages to: listproc@lists.yale.edu

1. For a temporary stop: set mendele mail

postpone

2. To resume delivery: set mendele

mail ack

3. To subscribe: sub mendele

first_name last_name

4. To unsubscribe kholile: unsub

mendele

****Getting

back issues****

The

Mendele Review archives can be reached at:

http://yiddish.haifa.ac.il/tmr/tmr.htm

***