The Mendele Review: Yiddish Literature and Language

(A Companion to MENDELE)

---------------------------------------------------------

Contents of Vol. 10.002 [Sequential No. 167]

Date:

1) This issue of TMR (ed).

2) Artists' Portraits of Yiddish Writers, 1st Series (David Mazower)

3) Yitskhak Laor calls

Biblical Hebrew a foreign language to Israeli Youth (ed.)

4) Is "Mit ale zibn

finger" a Yiddish idiom? (ed.)

5) Adina Bar-El's Grininke

beymelekh (ed.)

Click here to enter: http://yiddish.haifa.ac.il/tmr/tmr10/tmr10002.htm

1)----------------------------------------

Date:

From: ed.

Subject: This issue of TMR.

*The iconography of Yiddish

writers generally remains to be studied. David Mazower

here launches a study of portraiture of Yiddish authors by recognized artists.

He does not deny that the members of the classic trinity Mendele/Sholem-Aleykhem/Perets

were much photographed and drawn, but that these graphic efforts were not part

of a self-conscious recording-in-plastic-form the face or head of a literary

artist by a brother artist in another medium.

*Linguists differ as to the

nature and scope of Yiddish influence on Modern Israeli Hebrew. An echo of Ghil'ad Zuckermann's recent TMR

article was heard in the leading serious Israeli daily, HaAretz,

a paper – incidentally -- that is peppered with

Yiddish more than its editors may think. Yitskhak Laor, a prominent intellectual, writes that high school students

cannot read Biblical Hebrew without a crutch. This past week an article in HaAretz announced that English had surpassed Yiddish

in the number of slang terms it had loaned to Hebrew. The headline somehow

implied that Yiddish had lost in a competition. But Yiddish permeates spoken

Hebrew not only in lexicon, but in phonology and syntax. Almost nobody says Petakh tikVA and "Nu" is repeated by countless individuals countlessly.

*In an informal note, Seth Wolitz writes: "Mit ale zibn finger" is an idiom, because Dina Halpern [of The Dybbuk

film etc] when I showed her the Chagall piece broke out into laughter and said,

'Of course: Mit ale zibn

finger!' So it is an idiom!" However, I am still not satisfied (and not

because the argument of an idiom-source lacks cogency and reason). I simply

want evidence! From the folklorists and linguists rather than the art

historians – but anything substantial is welcome. Dina Halpern

was a famous Yiddish actress and Seth Wolitz, a

professor of Jewish Studies at the

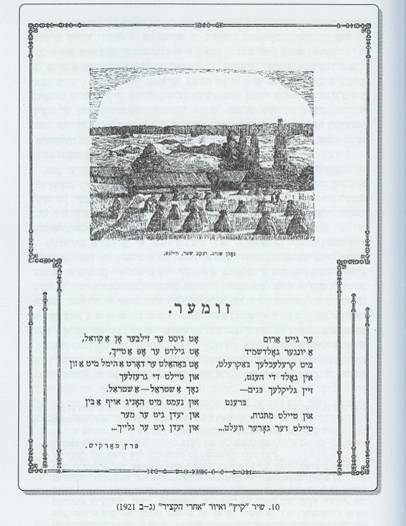

*Adina

Bar-El has centered her life around the writing, study and teaching of

literature for children, specializing in research on children's periodicals.

She has written over a dozen books for children, has taught education students

how to best use stories in their teaching and has brought together in periodic

symposia and seminars the authors of children's writing from all over Israel.

Her latest book is the last in a trilogy that examines periodicals for children

in Yiddish and Hebrew. She also has done preliminary work on Polish-Jewish

juvenile serials and is deep into a project to describe the ample field of Argentinian Yiddish children's periodicals.

2)----------------------------------------

Date:

From: David Mazower

Subject: Artists' Portraits of Yiddish Writers, 1st Series

Artists'

Portraits of Yiddish Writers

By

David Mazower

My interest in this subject

began with a casual inquiry. A journalist friend asked me to suggest a painting

of Sholem Aleykhem [Shalom Aleichem] to illustrate a magazine feature. I could think of plenty of photos but not a

single painting done while the great Yiddish writer was still alive. Nor could I recall ever having seen such a

portrait of Perets or Mendele,

or Goldfadn.

It’s as though we had no paintings by artist contemporaries of Tolstoy,

Dickens, Zola or Mark Twain. There will

almost certainly be one or two such portraits of Yiddish literature’s founding

fathers -- the exceptions that prove the rule -- but the comparison with other

world literatures is striking, as is the contrast with the interest shown in

later generations of Yiddish writers by their artist friends and peers.

Throughout my own childhood,

Sundays usually meant going to visit my grandparents at their flat in

There were at least a dozen

other paintings, drawings and sculptures made of Ash during his lifetime, and

several more of his wife Madzhe (Matilda). Many of

the artists were close friends of the writer, and others were no doubt

attracted by his celebrity and dramatic personality. But Ash was by no means

alone among contemporaries in being portrayed by some of the leading Jewish

artists of his day. Opatoshu, Sutskever,

Manger, Bashevis and many other lesser writers were

captured for posterity in a wide assortment of cartoons, sketches, silhouettes,

paintings and sculptures.

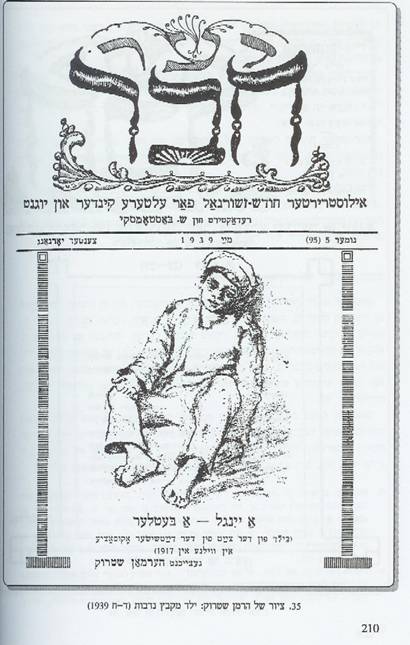

These artists’ portraits of

the second and third generation of modern Yiddish writers were produced for a

variety of reasons and served various functions. One of their primary uses was

as frontispiece or cover illustrations in books, commissioned by major

publishers of Yiddish literature such as Israel London in

The production of such

portraits, and their multiple uses, raises some interesting questions about the

changing status of Yiddish literature, and its changing image within the Jewish

world and beyond. It seems to me that the absence of such portraits of the

first generation of Yiddish writers is a reflection of two things mainly: the

ambivalence and snobbery that greeted the emergence of the new literature even

within the Jewish community, and presumably helped to persuade artists that the

early Yiddish masters were not profitable or fitting subjects for them to

paint; and secondly, a reflection of the fledging literature’s precarious

economy - the absence of networks of patronage, of proper means of support for

writers, established publishers and journals, and its own literary

institutions.

Within twenty or thirty years

much had changed, not least the emergence of a generation of artists who

admired and respected the Yiddish writers of their acquaintance, shared a

common language with them, and were only too happy to paint their portraits and

illustrate their works. In coming editions of The Mendele

Review, I hope to present some of the most striking of these Yiddish

writers portraits, and in the process to examine what their production and use

tell us about the emerging relationship between artist and writer in the

Yiddish world.

One further point worth

mentioning: many artists’ portraits of Yiddish writers have disappeared from

public view, some have survived only as reproductions in obscure publications,

while others have vanished entirely without trace except perhaps for a passing

mention in an autobiography or

memoir. It would be nice to think that the combined

sleuthing skills of the Mendele community could

unearth some of these precious artefacts of our

Yiddish cultural heritage, allowing them to be reproduced in future

installments of this series.

Gallery:

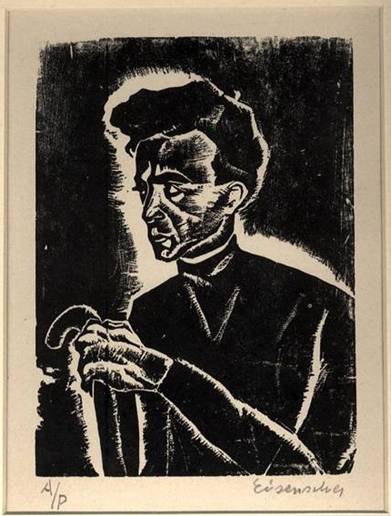

Jakob Eisenscher / Yankev Ayznsher (1896 - 1980)

Eisenscher was born in

Portrait of Itsik Manger

By Jakob

Eisenscher

Woodcut, 19 x 14 cm

signed and inscribed A.P. [nd, c.1926]

Private Collection,

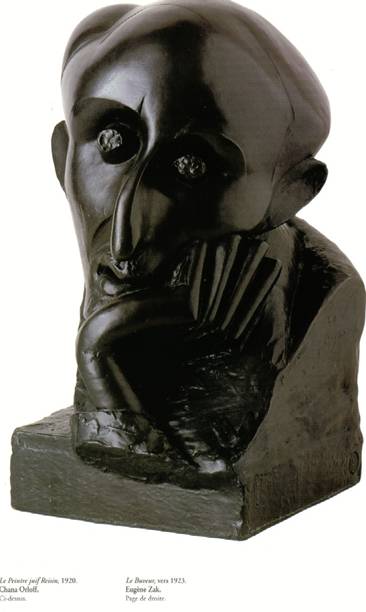

Chana Orloff (1888 - 1968)

Orloff was born in a small Ukrainian village. Her family settled in

Among her sitters were the

Hebrew writer Bialik, the Habimah

actress Khana Rovina, and Sholem Ash. The Yiddish dramatist Perets

Hirshbeyn and his wife, the poet Ester Shumyatsher, commissioned Orloff

to make a pair of matching busts. And in 1921 Orloff

exhibited this bust of the popular short story writer Avrom

Reyzn at the Salon des Independants.

It’s an exceptional piece, full of sensuous curves offset by the occasional

touch of Art Deco angularity, and it captures both the pathos of the author and

of his work. (Frequently exhibited and reproduced, for some reason it’s always

wrongly labelled as ‘the Jewish painter Reisen’ even in major exhibitions, such as ‘L’ecole de Paris 1904-1929 at the Musee

d’art Moderne in Paris in 2000-01.) Orloff remained in

occupied

Bust of Avrom

Reyzn

By Chana

Orloff

Bronze, 38.2 x 21.3 x 26.2 cm

1920

Jewish Museum,

Maurice Minkovski [Maurycy Minkowski] (1881 - 1931)

Born in

Moyshe Oyved was a well-known figure in

More on Minkowski,

see http://muse.jhu.edu/demo/shofar/v019/19.3baker.html

Portrait of Moyshe Oved [Edward Good]

(click here for higher resolution)

By Maurice Minkovski

Watercolour, 30 x 37.5 cm

signed and dated 1924

Ben

Uri Gallery - The

(See Zachary M. Baker's

excellent essay at

http://www.benuri.org.uk/Index-1.htm)

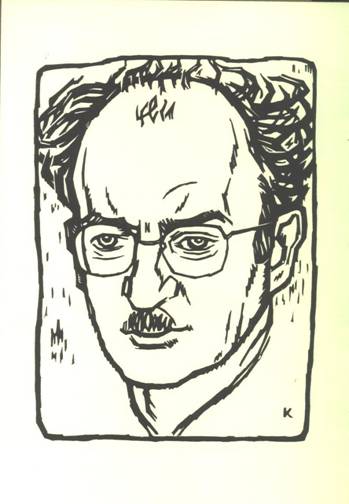

Artur

Kolnik (1890 - 1972)

Kolnik’s lyrical paintings and finely-detailed expressionist woodcuts drew

their inspiration from Jewish life in

Portrait of Avrom Sutskever

By Artur

Kolnik

Woodcut, illustration for the frontispiece of Avrom Sutskever, Gaystike erd (Spiritual

Earth)

3)---------------------------------------------

Date:

From: ed.

Subject: Yitskhak Laor

calls Biblical Hebrew a foreign language to Israeli youth

The central issue raised by Ghil‘ad Zuckermann in his recent essay "The Israeli

Language" [see TMR

vol 9, no 13 (29 December 2005)] is that of the

origins of Modern Israeli Hebrew, which he insists on calling

"Israeli". "Israeli", he maintains, is only very partially

a direct descendant of Biblical Hebrew. In various of his books and essays, Zuckermann argues that the average Israeli youth cannot

understand the Hebrew Bible without the help of commentaries, special

dictionaries and, in fact, 11 years of training. It now looks as if other

scholars agree with him. Such a view was recently clearly enunciated by one of

ìèòîé,

àçã ä÷ùééí áìîåã äúð"ê àéðå îöåé áñúéøä áéï ãú ìçéìåðéåú, àìà áàé-éëåìú

ìäëéø áëê ùäúð"ê ëúåá áìùåï æøä.

àéï ìáåâø úéëåï éùøàìé äéëåìú ìâùú ìôø÷ ùìà ìîã, áìé ôéøåù öîåã, áìé

îéìåï î÷øàé-òáøé. äàé-äëøä äæàú äéà çì÷ îï ääëçùä ä÷øåé 'ðöç éùøàì'.

éöç÷

ìàåø. "ùîùåï çéâø áùúé øâìéå äéä", äàøõ (20 éðåàø 2006), ä1.

4)---------------------------------------------------------

Date:

From: ed.

Subject: Is "Mit ale zibn finger" a Yiddish idiom?

See Chagall painting at: http://www.mcs.csuhayward.edu/~malek/Chagal4.html

In an informal note, Seth Wolitz writes:

"Mit ale zibn

finger" is an idiom, because Dina Halpern

[of The Dybbuk film etc] when I showed her the

Chagall piece broke out into laughter and said, "Of course: Mit ale zibn finger!" So it

is an idiom!

I am still not satisfied (and

not because the argument of an idiom-source lacks cogency and reason). I simply

want evidence! From the folklorists and linguists rather than the art

historians – but anything substantial is welcome. Dina Halpern

was a famous Yiddish actress and Seth Wolitz, a

professor of Jewish Studies at the

There are apparently multiple

interpretations of the seven fingers in the Chagall self-portrait. There

is no end of explicatory possibilities in the number seven. The origin has

been traced by at least one critic to a Yiddish expression "mit ale zibn finger" --

which I confess I do not know and which I have not found in any of the standard

handbooks of idioms or of proverbial expressions or in dictionaries.

Art historian Sandor Kuthy suggests that the

Yiddish folk expression Mit alle [sic- lp] zibn finger, "used to indicate the entirety of

energy expended in completion of a task, explains this strange physical anomaly

in the painting." Kuthy is cited by a number of

writers on this painting. Kuthy apparently was the

curator of a Chagall exhibition and is a Chagall specialist. On Kuthy and the symbolism of the number 7, see: http://www.jhom.com/topics/trees/seven/index.html.

"In Study for Self

Portrait with Seven Fingers 1911, Chagall presents us with the Jewish

fascination with numbers. Mit alle

[sic- lp] zibn finger, a

Yiddish folk expression… An enriched reading is gained in knowing that the

number seven is heavy with mystical overtones in Jewish expression, figuring

strongly with the concept of creation. G-d created the world in seven days. The

Kabbalah states that G-d created seven parallel

universes to our physical one. The three fathers and the four mothers in the

Bible gave birth to the Jewish nation. With his seven fingers, Chagall creates

new worlds with paint on canvas."

["Searching for the

Second Soul: The Hasidic Etymology of the Early Visual Language of Marc

Chagall" by Marleene Rubenstein]

Ellen McBreen

tells us – as do others – that [Chagall's] 'Self-Portrait with Seven Fingers'

(1912-13) … is emblematic of [the] expatriate condition. (According to a

Yiddish expression, to do something with seven fingers is to do it very well,

and very fast). See: http://www.paris-expat.com/guide/4-03_alchemy.html.

5)--------------------------------------------------------

Date:

From: ed.

Subject: Adina Bar-El's Grininke

beymelekh

---------------------------------------------------------

End

of The Mendele Review Vol. 10.02

Editor,

Leonard Prager

Subscribers to Mendele (see below) automatically receive The Mendele Review.

Send "to subscribe"

or change-of-status messages to: listproc@lists.yale.edu

a. For a temporary stop: set mendele mail postpone

b. To resume delivery: set mendele mail ack

c. To subscribe: sub mendele first_name last_name

d. To unsubscribe kholile: unsub mendele

****Getting

back issues****

The Mendele Review

archives can be reached at: http://yiddish.haifa.ac.il/tmr/tmr.htm

Yiddish

Theatre Forum archives can be reached at: http://yiddish.haifa.ac.il/tmr/ytf/ytf.htm

***