The Mendele Review: Yiddish Literature and Language

A

Companion to MENDELE

-----------------------------------------------------------------

Contents of Vol. 09.013

[Sequential No. 165]

Date:

1) This issue (ed.)

2) The Israeli Language (Ghil'ad Zuckermann)

3) More on kvetsh (ed.)

4) Yehoyesh's

khumesh with Ulrich Greve's

Jewish Calendar: Instructions

Click here to

enter: http://yiddish.haifa.ac.il/tmr/tmr09/tmr09013.htm

1)-----------------------------------------------------------------------

Date:

From: Leonard Prager

Subject: This issue of

TMR

Ghil'ad Zuckermann's new book, Hebrew As Myth [Am Oved] will be

published shortly and he here gives a refined restatement of the

argument he presented polemically in his reply to the Forward's Philologus in TMR 8.013 (December 2004). [See http://www2.trincoll.edu/~mendele/tmr/tmr08013.htm].

Zuckermann commands a position midway between

the traditionalists -- semiticists largely who cling

to the view of continuous development of a Hebrew language from

biblical times to today -- and the "revisionists" for whom

Hebrew is relexified Indo-European. Zuckermann states squarely: "Israeli is a hybrid

language based on both Hebrew and Yiddish" as well as on many other

languages. Since his copious review of the Oxford English-Hebrew Dictionary

(in the International Journal of Lexicography, Vol. 12, No. 4 (1999):

325-346) -- and probably before -- Zuckermann has

wrangled with the glottonomy issue and it has

unnecessarily won him sharp critics. Zuckermann by

no means denies the productive powers and expressive capacity of the language

of the State of Israel commonly called Hebrew. He insists on both its

Indo-European and Semitic origins, its immense debt to Yiddish, its essential

newness -- and his name for it: "Israeli." He concludes: "Whatever we choose to call

it, we should acknowledge, and celebrate, its complexity." The appearance of Zuckermann's

new book will doubtless stimulate much discussion.

In the last issue of TMR

I boldly asserted that the verb kvetshn in

Yiddish does not mean 'to complain', though to kvetch has clearly come

to mean that in English. What bothered me was the notion that Yiddish itself in

toto was being assigned the quality of griping.

Now that the lexical question has been raised we are constrained to pursue it

further.

Instructions for

downloading a marvelous Jewish Calendar with integrated weekly Khumesh portion in Yehoyesh's

classic Yiddish translation.

2)-----------------------------------------------------------------

Date:

From: Ghil'ad Zuckermann

<gz208@cam.ac.uk>

Subject: The Israeli Language

THE ISRAELI LANGUAGE

Ghil‘ad Zuckermann

http://www.zuckermann.org Fascinating and

multifaceted, Israeli (Zuckermann 1999, a.k.a.

‘Modern Hebrew’) is a ‘non-genetic’ language from the point of view of Hebrew;

there was no continuous chain of native speakers from spoken Hebrew to Israeli.

Hebrew was spoken by the Jewish people after the so-called conquest of

Unlike Maskilic Hebrew (i.e. the Hebrew of the Haskalah,

the 1770-1880 Enlightenment Movement led by Moses Mendelssohn and Naphtali Herz Wessely),

a literary language, Israeli is a living mother tongue. Its formation was

facilitated in Eretz Yisrael

(‘

Itamar Ben-Avi (1882-1943, born as

Ben-Zion Ben-Yehuda), Eliezer

Ben-Yehuda’s son, is symbolically considered to have

been the first native Israeli-speaker. He was born one year after Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, a native

Yiddish-speaker, conversant in Russian and French, arrived in Eretz Yisrael. Eliezer and his wife, Dvora,

spoke to Itamar only in Hebrew despite their not

being native speakers. Itamar, who only started to

speak at the age of four, confessed that he uttered his first word after his

father, who was obsessive about Hebrew, found Dvora

singing a Russian lullaby to Itamar. Eliezer became furious and smashed a wooden table to

pieces. ‘Seeing my father furious and my mother […] crying, I started to

speak’, Itamar wrote in his autobiography (Ben-Avi 1961: 18).

But it was not until the

beginning of the twentieth century that Israeli was first spoken by a

community, which makes it approximately 100 years old. The first children born

to two Israeli-speaking parents were those of couples who were graduates of the

first Israeli schools in Eretz Yisrael,

and who had married in the first decade of the twentieth century (see Rabin

1981: 54).

In April 2000, the

oldest native Israeli-speaker was Dola Wittmann (in her late 90s), Eliezer

Ben-Yehuda’s daughter, who also happens to be one of

the first native Israeli-speakers. When Orthodox Jews desecrated her father’s

grave with obscene graffiti (because, in their view, vernacularizing

the ‘holy language’ was a sin), Dola simply asked,

‘What language did they write in?’ When the answer came back, ‘Hebrew’, she

took it as an admission of defeat by his critics.

Israeli is one of the

official languages – with Arabic and English – of the State of Israel, spoken

to varying degrees of fluency by its 6.8 million

citizens – as a mother tongue by most Israeli Jews (whose total number is

5,235,000), and as a second language by Israeli Muslims (Arabic-speakers),

Israeli Christians (e.g. Russian- and Arabic-speakers), Israeli Druze (Arabic-speakers)

and others. It is also spoken by some non-Israeli Palestinians, as well as by a

small number of Diaspora Jews.

During the past century,

Israeli has become the primary mode of communication in all domains of public

and private life. With the growing diversification of Israeli society, it has

come also to highlight the absence of a unitary civic culture among citizens

who seem increasingly to share only their language.

Issues of language are

so sensitive in

One could see in these rebukes the common nostalgia of a conservative older

generation unhappy with ‘reckless’ changes to the language – cf. Aitchison

(2001), Hill (1998), Milroy and Milroy

(1999) and Cameron (1995). But normativism in Israeli contradicts the usual ‘do not

split your infinitives’ model, where there is an attempt to enforce the grammar

and pronunciation of an elite social group. Using a ‘do as I say, don’t do as I

do’ approach, Ashkenazic Jews (most of them originally native

Yiddish-speakers), who have usually controlled key positions in Israeli

society, urged Israelis to adopt the pronunciation of Sephardic Jews

(many of them originally native Arabic-speakers), who happen to have been

socio-economically disadvantaged. In fact, politicians, educators and many laymen

are attempting to impose Hebrew grammar on Israeli speech, ignoring the fact

that Israeli has its own grammar, which is very different from that of Hebrew.

The late linguist Haim Blanc once took his young daughter to see an Israeli

production of My Fair Lady. In this version, Professor Henry Higgins teaches

Eliza Doolittle how to pronounce /r/ ‘properly’, i.e. as the Hebrew alveolar

trill, characteristic of Sephardim (cf. Judaeo-Spanish,

Italian, Spanish), rather than as the Israeli lax uvular approximant (cf. many

Yiddish and German dialects). The line ‘The rain in

A language is an

abstract ensemble of idiolects – as well as sociolects,

dialects etc. – rather than an entity per se. It is more like a species

than an organism (cf. Mufwene 2001: 11). Still,

linguists attempt to generalize about communal languages, and, in fact, the

genetic classification of Israeli Hebrew has preoccupied scholars since the

beginning of the twentieth century. The traditional view suggests that it is

Semitic: (Biblical/Mishnaic) Hebrew revived (e.g.

Rabin 1974). Educators, scholars and politicians have propagated this view. The

revisionist position defines Israeli as Indo-European: Yiddish relexified, i.e. Yiddish, most revivalists’ máme lóshn

(mother tongue), is the ‘substratum’, whilst Hebrew is only a ‘superstratum’ providing lexicon and frozen morphology (cf.

Horvath and Wexler 1997).

From time to time it is

alleged that Hebrew never died (e.g. Haramati 1992,

2000, Chomsky 1957: 218). It is true that throughout its literary history

Hebrew was used as an occasional lingua franca. However, between the second and

nineteenth centuries it was no one’s mother tongue. The development of a

literary language is very different from that of a native language. But there

are many linguists who, though rejecting the ‘eternal spoken Hebrew mythology’,

still explain every linguistic feature in Israeli as if Hebrew never died. For

example, Goldenberg (1996: 151-8) suggests that Israeli pronunciation

originates from internal convergence and divergence within Hebrew.

I wonder, however, how a

literary language can be subject to the same phonetic and phonological

processes as a mother tongue. I argue, rather, that the Israeli sound system

continues the (strikingly similar) phonetics and phonology of Yiddish, the

native language of almost all the revivalists. These revivalists very much

wished to speak Hebrew, with Semitic grammar and pronunciation, like Arabs.

However, they could not avoid the Ashkenazic mindset

– and consonants – arising from their European background.

Unlike the

traditionalist and revisionist, my own hybridizational

theory acknowledges the historical and linguistic continuity of both Semitic

and Indo-European languages within Israeli. ‘Genetically modified’,

semi-engineered Israeli is based simultaneously on Hebrew and Yiddish (both

being primary contributors – rather than ‘substrata’), accompanied by a

plethora of other contributors such as Russian, Polish, German, Judaeo-Spanish (‘Ladino’) Arabic and English. Therefore,

the term Israeli is far more appropriate than Israeli Hebrew, let

alone Modern Hebrew or Hebrew (tout court).

What makes the

‘genetics’ of Israeli grammar so complex is the fact that the combination of

Semitic and Indo-European influences is a phenomenon occurring already within

the primary (and secondary) contributors to Israeli. Yiddish, a Germanic

language with a Romance substratum (and with most dialects having undergone Slavonicization), was shaped by Hebrew and Aramaic. On the

other hand, Indo-European languages, such as Greek, played a role in (Semitic)

Hebrew. Moreover, before the emergence of Israeli, Yiddish and other European

languages influenced Medieval and Maskilic variants

of Hebrew (see Glinert 1991), which, in turn,

influenced Israeli (in tandem with the European contribution). This adds to the

importance of the Congruence Principle (Zuckermann

2003):

If a linguistic feature

exists in more than one contributor, it is more likely to persist in the Target

Language.

The distinction between

forms and patterns (Zuckermann 2006) is crucial too.

In the 1920s and 1930s, gdud meginéy hasafá,

‘the language defendants regiment’ (see Shur 2000),

whose motto was ivrí, dabér ivrít

‘Hebrew [i.e. Jew], speak Hebrew!’, used to tear down signs written in

‘foreign’ languages and disturb Yiddish theatre gatherings. However, the

members of this group did not look for Yiddish and ‘Standard Average European’

patterns in the speech of the Israelis who did choose to speak ‘Hebrew’. [The

term ‘Standard Average European’ was first introduced by Whorf (1941: 25) and

recently received more attention by Haspelmath (1998,

2001) and Bernini and Ramat

(1996) – cf. ‘European Sprachbund’ in Kuteva (1998).]

This is, obviously, not

to say that the revivalists, had they paid attention to patterns, would have

managed to neutralize the impact of their mother tongues, which was often

subconscious (hence the term ‘semi-engineered’). As Mufwene

observes, ‘linguistic change is inadvertent, a consequence of “imperfect

replication” in the interactions of individual speakers as they adapt their

communicative strategies to one another or to new needs’ (2001: 11). Although

they have engaged in a campaign for linguistic purity, the language the

revivalists ‘created’ often mirrors the very cultural differences they sought

to erase (cf. mutatis mutandis Frankenstein’s monster, or the golem).

The alleged victory of Hebrew over Yiddish was, in fact, a Pyrrhic one.

Victorious ‘asthmatic’ Hebrew is, after all, partly European at heart. Yiddish

and Standard Average European survive beneath ‘osmotic’ Israeli grammar.

Had the revivalists been

Arabic-speaking Jews (e.g. from

Whenever an empty territory undergoes settlement, or an earlier population is dislodged by invaders, the specific characteristics of the first group able to effect a viable self-perpetuating society are of crucial significance to the later social and cultural geography of the area, no matter how tiny the initial band of settlers may have been [...] in terms of lasting impact, the activities of a few hundred, or even a few score, initial colonizers can mean much more for the cultural geography of a place than the contributions of tens of thousands of new immigrants generations later.

Harrison et al. (1988)

discuss the ‘Founder Effect’ in biology and human evolution, and Mufwene (2001) applies it as a creolistic

tool to explain why the structural features of so-called creoles (which he

regards as ‘normal languages’ just like English) are largely predetermined by

the characteristics of the languages spoken by the founder population, i.e. by

the first colonists. I propose the following Founder Principle in the context

of Israeli:

Yiddish is a primary

contributor to Israeli because it was the mother tongue of the vast majority of

revivalists and first pioneers in Eretz Yisrael at the crucial period of the beginning of

Israeli.

The Founder Principle

works because by the time later immigrations came to

At the same time – and

unlike anti-revivalist revisionists – I suggest that lethargic liturgical

Hebrew too fulfills the criteria of a primary contributor for the following

reasons: (i) Despite millennia without native

speakers, it persisted as a most important cultural, literary and liturgical

language throughout the generations; (ii) Revivalists made a huge effort to

revive it and were, in fact, partly successful.

The impact of Yiddish

and Standard Average European is apparent in all the components of the

language but usually in patterns rather than in forms. That said,

Israeli demonstrates a unique spectacular split between morphology and

phonology. Whereas most Israeli Hebrew morphological forms, e.g.

discontinuously conjugated verbs, are Hebrew, the phonetics and phonology of

Israeli — including of these very forms — are European. One of the reasons for

overlooking this split is the axiom that morphology — rather than phonology —

is the most important component in genetic classification. In fact, such a morpho-phonological split is not apparent in most languages

of the world and is definitely rare in ‘genetic’ languages.

The revivalists’ attempt

to belie their European roots, negate diasporism and

avoid hybridity (as, in fact, reflected in Yiddish

itself) failed. Thus, the study of Israeli offers a unique insight into the

dynamics between language and culture in general and in particular into the

role of language as a source of collective self-perception. Linguists and

community leaders seeking to apply the lessons of Israeli in the hope of

reviving no-longer spoken languages (e.g. Amery 1994, 1995, 2000; cf. Clyne 2001; Fishman 1991, 2001; Thieberger

1988) should take warning. When one revives a language, even at best one should

expect to end up with a hybrid. I maintain that Israeli is a ‘non-genetic’,

layered, Semito-European language, only partially

engineered. Whatever we choose to call it, we should acknowledge, and

celebrate, its complexity.

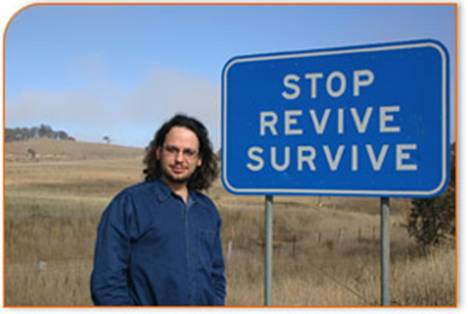

* Stop Revive Survive is

a sign intended to urge drivers to nap.

Zuckermann playfully reanalyses it to

declare that the revival of Hebrew also includes the survival of Yiddish --

even though the revivalists did not intend this!

3)------------------------------------------------------------------

Date:

From: ed.

Subject: More on

kvetsh

Dr. Meyer Wolf, a

keen-eyed Yiddish linguist, has pointed to a Yiddish noun kvetsh

meaning 'hypochondriac'. See Nokhem Stutshkov, Der oytser fun der yidisher shprakh.

Under the semantic category krankeyt,

'sickness' [#420], the nouns khekhlyak, khorkhlyak, zdekhlyak, khvetshke, KVETSH and kholyere

are grouped together on p. 411. Of all these words the only one that is phonotactically a candidate for English borrowing is kvetsh (spelled kvetch). This Yiddish

substantive could very well be the seed from which a Jewish-English verb

meaning 'to complain' arose.

4)--------------------------------------------------------------

Date:

From: ed.

Subject: Yehoyesh's khumesh

with Ulrich Greve's Jewish Calendar: Instructions

Download the latest

version of the Jewish Calendar Program for Windows 95/98/2000/ME/XP: http://www.tichnut.de/jewish/index2.htm

(by clicking on here on left-hand side) and the files for the Khumesh in Yiddish. After downloading the

calendar, close all running applications (since the computer is restarted after

installation) and execute the downloaded file. Then go to the manual page where

details of installation of the Khumesh

in Yiddish are described and install the self-extracting archive. By clicking

on a Shabbat or holiday in the calendar and then clicking on "View torah

reading in Yiddish!", the torah sections are displayed in Yiddish. The Khumesh in Yiddish must be downloaded

and installed separately. On the download page of the Jewish Calendar

for Windows 95/98/2000/ME/XP, the short manual at http://www.tichnut.de/jewish/jewcalreadme2.htm

contains these instructions. Download the self-extracting archive tpr.exe

from http://www.tichnut.de/jewish/tpr/tpr.exe.

Run the downloaded tpr.exe file in order to extract the .tpr files with the Khumesh

in Yiddish. Copy the extracted .tpr files (bamidbar.tpr, breyshis.tpr,

dvorim.tpr, shmoys.tpr and vayikro.tpr)

into the same directory where the Jewish Calendar Program is installed (by

default, C:\CAL80).

---------------------------------------------------------------

End of The Mendele Review Vol. 09.013

Editor,

Leonard Prager

Subscribers to

Mendele (see below) automatically receive The Mendele Review.

Send "to

subscribe" or change-of-status messages to: listproc@lists.yale.edu

a. For a temporary stop: set mendele mail postpone

b. To resume delivery: set mendele mail ack

c. To subscribe: sub mendele first_name last_name

d. To unsubscribe kholile: unsub mendele

****Getting

back issues****

The Mendele Review

archives can be reached at: http://yiddish.haifa.ac.il/tmr/tmr.htm

Yiddish

Theatre Forum archives can be reached

at: http://yiddish.haifa.ac.il/tmr/ytf/ytf.htm

***