The Mendele

Review: Yiddish Literature and Language

(A Companion to MENDELE)

Tenth Anniversary Issue

---------------------------------------------------------

Contents of Vol. 11.004 [Sequential No. 181]

Date:

1) This issue of TMR (ed).

2) Portraits of Yiddish Authors, Series 6 (David Mazower)

3) Mordkhe Schaechter ò"ä on Yiddish der

kvetsh 'accent'

4) A Yiddish Moment in the American Novel (from Jean Hanff

Korelitz, The

5) Comments on the above passage (ed.)

6) Tsenerene in a mid-19th century Jerusalem Ashkenazi

girls' school (ed.)

7) Periodicals Received: Jiddistik Mitteilungen Nr.

36 [November 2006]; Lebns-fragn 57: 651-2 [January-March 2007]

Click here to enter: http://yiddish.haifa.ac.il/tmr/tmr11/tmr11004.htm

1)----------------------------------------------------------

Date:

From: ed.

Subject: This issue of TMR.

*Volume 1, No. 1

of The Mendele Review appeared on

2)----------------------------------------------------------

Date:

From: David Mazower

Subject: Portraits of Yiddish Authors, Series 6

TMR

Portraits of Yiddish Writers / Series 6

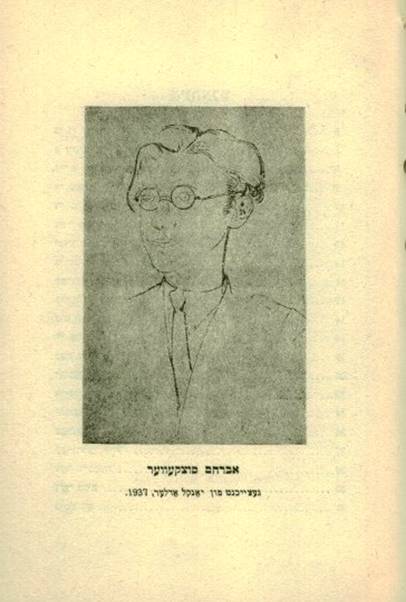

Yankl

Adler (Jankel Adler), 1895 – 1949

Portrait

of Avrom Sutskever (born

1913)

(present whereabouts unknown)

Adler was born

into a large orthodox family in the mainly Hasidic community of Tuszyn, near

Adler is often

viewed within the exclusive context of the German art scene. Less well known is

the fact that he had close and enduring friendships with many leading Yiddish

writers and remained an influential figure in Yiddish cultural circles from his

early days in

In Lodz in the years immediately following the First

World War, he helped to found the Yung Yidish

literary and artistic circle which also included artists Marek

Szwarc, Yitskhok Broyner (Vincent Brauner) and Henokh Bartshinski, the composer Henokh Kon, and the playwright Moyshe Broderzon.

Adler

illustrated a number of books by Yiddish writers in the 1920s and 30s. Most of

these are now exceptionally scarce. The list that follows is compiled from

various sources and would benefit from careful checking against the original

copies. Almost certainly incomplete, it includes:

Moyshe Broderzon, Tkhiyes-hameysim:

misterye, Lodz, 1920 (cover design by Adler)

Moyshe Broderzon, Shvarts-shabes,

Lodz, 1921 (author’s portrait by Adler)

Khayim Krul, Loybn, Lodz, 1920

(illustrations by Adler and others)

Y M Nayman, Yon

tev in der vokhn: lider, Warsaw, 1936

(author’s portrait by Adler)

Avrom Sutskever, Lider, Warsaw

1937 (author’s portrait by Adler)

Avrom Sutskever, Lider fun geto, New York, 1946 (author’s portrait by Adler)

Avrom Zak: Unter di fligl fun toyt, Warsaw, 1921

(twelve illustrations by Adler).

Reyzl Zhikhlinski, Lider ,

Warsaw, 1936

In exile in

Adler’s

portrait of Sutskever, done in 1937, appears as the

frontispiece to a small pamphlet of the poet’s verse entitled Lider

fun geto, (Ghetto Poems). Written by Sutskever in the Vilna ghetto, they were buried in a

cellar, retrieved once the German occupation was over, and sent by Sutskever from

Sutzkever ’s links

with Jewish art deserve closer attention than I can give them here. He has

always been careful in his choice of illustrators and artistic collaborators

and his portrait has been painted by many of the leading modern Jewish artists

(including Chagall, Kolnik and Reuven

Rubin). Sutskever himself is an able amateur artist

(my copy of his collected works, dedicated to his

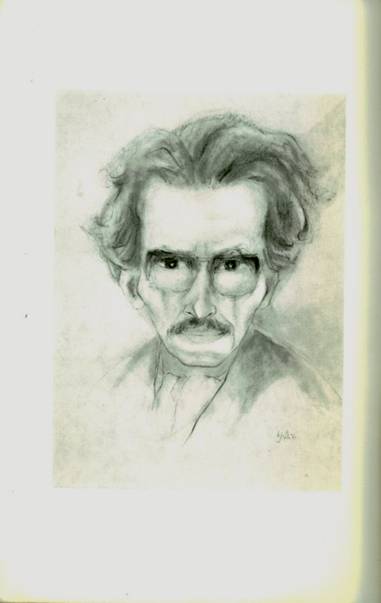

Halina Olomucki (born 1921)

Portrait

of Ber Kutsher (1893 - 1978)

(present whereabouts unknown.)

Halina Olomucki

was born in

Olomucki held her first post-war

exhibition in

Ber Kutsher,

born in 1893, was a journalist and versatile writer of fiction and a regular

contributor to the Warsaw Yiddish daily Haynt

from 1916. Kutsher wrote novels, humorous sketches,

plays, a biography of the popular Jewish strongman Zishe

Breitbart, and an important volume of memoirs about

Jewish culture in inter-war

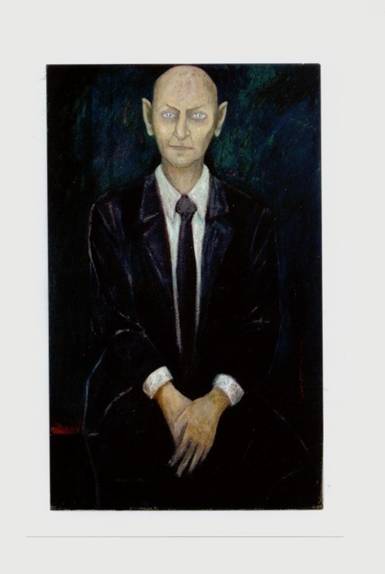

Hazel

Karr

Portrait

of Isaac Bashevis Singer (Y. Bashevis)

1905 – 1991

(Collection of the artist, Paris )

There are many

fine portraits of Bashevis, but Hazel Karr’s almost

life-size oil painting has a unique fascination. Karr is a professional artist

whose work has been shown in numerous individual and group shows in

When I visited

Karr some years ago in her apartment in

Karr’s

impressive portrait has never been exhibited in public and TMR is

grateful to Hazel Karr for giving us permission to reproduce it here for the

first time.

3)----------------------------------------------------------

Date:

From: ed.

Subject: Mordkhe Schaechter

(ò"ä) on

Yiddish der kvetsh

'accent'

Mordkhe Schaechter

(ò"ä) on

Yiddish der kvetsh

'accent'

We thank the Yiddish League for permission to publish the above essay.

4)----------------------------------------------------------

Date:

From: ed.

Subject: A Yiddish Moment in the American

Novel

"And she helped Naomi recover the

dialect of sarcasm, a language that had atrophied from lack of use. It amazed

her how pleasurable it was to speak this way. It made her remember nights in

college, in crowded rooms lubricated by marihuana and noisy with students who

couldn't quite pronounce the names of their great-grandparents' shtetl ('I'm pretty sure it was called Anatevka,' one pathetic girl had actually said) but thought

it was somewhere in

[Jean Hanff Korelitz, The

5)----------------------------------------------------------

Date:

From: ed.

Subject: Comments on the Korelitz passage above

The young man in the story thinks a town

in

But ignorance of one's origins is but a

subtext in this passage, whose main subject is the loss and temporary, fitful

recovery of an earlier language-style and mode of communication, an English suffused with Yiddish and preserving

warmly-recalled Yiddish words and phrases. Meeting someone with similar

background the heroine can relax into that aggressive conversational register

she grew up with. She had sacrificed a core quality in her being in the interest

of an all-too-expensive acculturation. Contemporary American novels flow over

with Yiddishisms and references to Yiddish, but

rarely embody the profound insight displayed in this key sentence:

"Their pitch had taken generations of

a conjoint heritage to perfect, and yet she had lost it willingly over this

past decade, or at least without putting up a fight, and only now did she feel

the cost of that, as she felt the intense gratification of hearing herself

think and think aloud."

6)----------------------------------------------------------

Date:

From: ed.

Subject: Tsenerene in a mid-19th century Jerusalem Ashkenazi

girls' school

Mary Eliza Rogers. Domestic Life in

In

this charming personal travelogue of mid-19th century Palestine,

MER, sister of the British Consul at Damascus (Jerusalem and Haifa as well)

prefaces her book as follows: "While residing in Palestine, I was placed

in circumstances which gave me unusual facilities for observing the inner

phases of Oriental Domestic Life."

She describes a visit to a girls' school in the Jewish Quarter of

Jerusalem where Sefardi and Ashkenazi pupils occupy

separate classrooms. After describing the Arabic-speaking Sefardi

girls, she enters the Ashkenazi preserve. The 'German' book she hears

being read from is undoubtedly the perennially popular Old Yiddish classic Tsenerene. The writer repeats the widespread

half-truth that this book was for women and children; actually it was also read

by men who did not know Hebrew well.

"We went downstairs to the second

German room, where most of the girls were between thirteen and fifteen years of

age, and the rest younger. We heard two of the eldest

read, with emphasis, several pages from the life of Moses – a book written

expressly for the use of women and children. It is a paraphrase of the Bible

history of Moses, in a curious harsh dialect, being a compound of Hebrew and

German. It is printed in Hebrew characters, and embellished with quaint and

curious woodcuts, in the style of the followers of Albert Duerer."

[p.315]

7)----------------------------------------------------------

Date:

From: ed.

Subject: Periodicals Received: Jiddistik Mitteilungen Nr. 36 [November 2006]; Lebns-fragn

57: 651-2 [January-March 2007]

Lebns-fragn; sotsialistishe khoydesh-shrift far politik, gezelshaft un kultur

– to assign this veteran journal its full Yiddish title – has now entered the

internet with an attractively designed website: http://www.lebnsfragn.com.

This Bundist but far from

dogmatic journal is now in its 57th year of publication. We welcome

this newcomer to Yiddish cyberspace and wish its energetic editor and key

contributor Yitskhok Luden

success in continuing for as many years as possible a political and cultural

organ which is both Yiddish and Israeli. The current issue has poems by Rivke Basman, reportage from

retired cardiologist and journalist Khariton Berman

(from "Shvartstime," i.e. Bela Tserkov), a book review by

Jiddistik Mitteilungen; Jiddistik in Deutschsprachigen Laendern No. 36 (November

2006) is characteristically rich in scholarly aids. Karl-Heinz Best's lead

essay on the quantitative dimension of Yiddish loanwords in German contains a

two-page list of references and the url

of his own website: http://wwwuser.gwdg.de/~kbest.

Two significant figures in the world of Yiddish, Majer

Bogdanski and Eli Katz, are eulogized in some depth

by Heather Valencia and Erica Timm respectively. Very

solid reviews of important books in the Yiddish field are an especially

valuable feature of this issue: Elvira Groezinger on Estraikh Gennady In

Harness. Yiddish Writers' Romance with Communism (

-----------------------------------------------------------

End of The Mendele Review Vol. 11.004

Editor, Leonard

Prager

Subscribers to Mendele

(see below) automatically receive The Mendele Review.

Send "to subscribe" or change-of-status messages

to: listproc@lists.yale.edu

a. For a temporary stop: set mendele

mail postpone

b. To resume

delivery: set mendele mail ack

c. To

subscribe: sub mendele first_name

last_name

d. To

unsubscribe kholile: unsub mendele

****Getting back issues****

The Mendele

Review archives can be

reached at: http://yiddish.haifa.ac.il/tmr/tmr.htm

Yiddish Theatre Forum archives can be reached at: http://yiddish.haifa.ac.il/tmr/ytf/ytf.htm

Mendele on the web: http://shakti.trincoll.edu/~mendele/index.utf-8.htm