The

Mendele Review: Yiddish Literature and Language

(A Companion to MENDELE)

---------------------------------------------------------

Contents of Vol. 10.001 [Sequential No. 166]

Date: 30 January 2006

1) This issue (ed).

2) Yet More on kvetsh (Hugh Denman)

3) knie or kneye (ed.)

4) Hebrew Poets on the Jewish-Arab Conflict (Haggai Rogani)

5) Coming Issues: Artists' Portraits of Yiddish Writers presented by David

Mazower

Click here to

enter: http://yiddish.haifa.ac.il/tmr/tmr10/tmr10001.htm

1)----------------------------------------

Date: 30

January 2006

From: ed.

Subject: This issue of TMR.

*A letter from

Hugh Denman continues our ongoing discussion of Yiddish kvetsh (as distinct

from the Jewish-English origin word kvetch. *The word knie is

encountered in a Sholem-Aleykhem story and it proves troublesome. *The central content of this issue of TMR

is Haggai Rogani's new book on the ways in which contemporary Hebrew poets

responded in their work to the Jewish-Arab conflict. The Hebrew poets

discussed by Rogani all had some connection with Yiddish. Uri-Tsvi Greenberg is

a major Yiddish poet. Vilna-born Abba Kovner wrote his earliest poems in both

Yiddish and Hebrew. Yiddish is an important element in the poetic language of

Avot Yeshurun. In the same period covered in Rogani's work, scores of Yiddish

poets, some of considerable distinction, lived and wrote in Israel. A study of

the Palestine theme in their verse would be of considerable interest in itself

and would go far to illuminate the little known body of Yiddish writing in the

Land of Israel. To what degree did the experience of these Yiddish poets

parallel that of the nine poets in Rogani's study? We give here the English

abstract of Rogani's book. Haggai

Rogani. Facing the Ruined Village: Hebrew Poetry and the Jewish-Arab

Conflict 1929-1967.

חגי רוגני, מול הכפר שחרב: השירה העברית והסכסוך

היהודי-ערבי 1929 –1967. חיפה: פרדס, 2006

מסת"ב: ISBN:

965-7171-24-5 [מחיר קטלוגי:

78 ₪] פרדס הוצאה לאור, רח' יוסף 29, הדר

הכרמל, חיפה 33145. Price outside Israel: 17 dollars postpaid. contact@pardes.co.il

The title of

Rogani's book is from Lea Goldberg's poem "Olive Trees."

עָמְדוּ בְּנִסְיוֹן

הַשָּׁרָב

וּבָאוּ בְּסוֹד הַסַּעַר –

וּכְנֶצַח נִצְּבוּ

בְּמוֹרַד

הַגִּבְעָה מוּל הַכְּפָר שֶׁחָרַב

מַכְסִיפִים בְּאוֹרוֹ

הַצּוֹנֵן שֶׁל הַסַּהַר.

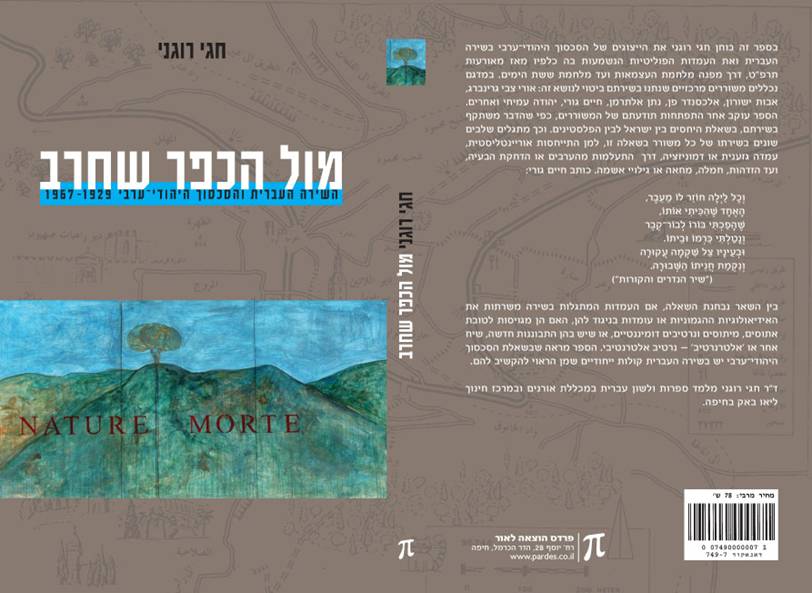

The cover, designed by David Gutsman, features Salam

Munir Diab's painting "Nature Morte" (2002).

2)---------------------------------------------------

Date: 30

January 2006

From: Hugh Denman

Subject: Yet More on kvetsh

Dear Editor,

Leafing idly

through Sholem-Aleykhem earlier today, I came across the following:

ikh bin mir eyner aleyn,, a fray feygele, in der groyser breyter velt... nor

tsulib mir aleyn hot zikh tsenumen di shmekndike royz, tseshpreyt der langer,

der geler "sonishnik", tsetsviklt un tseshprenklt dos gantse breyte

feld mit ale antiklekh fun der milder natur. keyner kvetsht mikh nisht, keyner

shtert mikh nisht, akhuts got un ikh kon mir ton, vos ikh vil... ['Grins oyf

shvues' (1903), Mayses far yidishe kinder 2, AV-F2, 8, 123].

איך בין מיר אײנער

אַלײן ,,אַ פֿרײַ פֿײגעלע, אין דער גרױסער ברײטער װעלט... נאָר צוליב מיר אַלײן האָט

זיך צענומען די שמעקנדיקע רױז, צעשפּרײט דער לאַנגער, דער געלער "סאָנישניק",

צעצװיקלט און צעשפּרענקלט דאָס גאַנצע ברײטע פֿעלד מיט אַלע אַנטיקלעך פֿון דער

מילדער נאַטור. קײנער קװעטשט מיך נישט,

קײנער שטערט מיך נישט,

אַחוץ גאָט און איך קאָן מיר טאָן, װאָס איך װיל... ['גרינס אױף שבֿועות'

(1903), מעשׂיות פֿאַר ייִדישע

קינדער 2 AV-123,

8, F2 ]

The narrator,

a young Rabinovitsh persona, has managed to get away from his mother, from home

and from the whole shtetl with the pretext of going to gather 'grins' for the

festival. He is reveling in the unwonted freedom of the open fields. No one is

badgering, pestering or otherwise bothering him.

The story was

written three years before the author's first visit to the United States.

However, note that the usage is transitive. Perhaps it is not quite accurate to

say that in genuine East European Yiddish the meaning of kvetshn is

limited to 'to pinch' and 'to place stress on a syllable'. Perhaps the American

twist consists in the switch from transitive to intransitive and then on to

become a substantive, both semasiological processes typical of American

English.

Of course, the

main point of your piece in TMR was not so much lexical as a cri de

coeur against superficial attempts à la Rosten to limit Yiddish to a

single register. I haven't read Wex either so I cannot comment on whether

he is guilty of this, but certainly his title is unfortunate.

Yours truly,

Hugh Denman

3)------------------------------------------------------------------

Date: 30 January 2006

From: ed.

Subject: knie or kneye

Sholem-Aleykhem in "Zisl der

yoyred" writes "a knie erd," which I have tentatively chosen to

regard as a spelling mistake for "a kneye erd." I have had a lively

discussion with Meyer Wolf, who characteristically throws light on such

matters, but a few issues remain unsolved. Here is the entire passage in

Yiddish:

אָן זיסלען װאָלט זיך געצי אָנגעכאַפּט מיט בײדע הענט. װער

איז געצי דער שמש, און װער איז זיסל דער יורד? ער װאָלט נאָך געמעגט אױסשלאָגן

בײַ אים אַ קנײע ערד, אָט דער שמש, אַ רוח אין זײַן טאַטנס טאַטן אַרײַן!

My guess is that a kneye

erd means 'a hole in the ground' and is a crude way of saying 'a

grave'. The yoyred in the sketch is complaining that his rich cousin

won't even give him a plot of ground for his burial when he dies. It is

interesting that the word, which I spell here as kneye, is

spelled several different ways, even in the same dictionary. I have not met

this word in Sholem-Aleykhem before. He spells it kuf, nun, yud, ayin in the

edition from which I am citing. I have found the word in a dictionary spelled

with two yuds. It is missing from Harkavi and not found it in Stutshkov. There

is a Polish word knieja but the meaning is very different. What is the

etymon? I now spell our word kuf nun tsvey yudn ayin, but in the printed

Sholem-Aleykhem text (Forverts edition) there is only one yud.

One thread of thought that both

Meyer and I followed briefly connected to Yiddish knie 'knee'. Meyer

wrote: "Second thoughts on kneye erd. kuf-nun-yud-ayin spells knie,

a variant of kni 'knee', widespread in the literary language. The corresponding verb for

'kneel' is knie|n, e.g. er kniet. knie erd. On this guess, it would mean something like 'a small piece of land to

kneel on'." Sounds good but we decided it was wrong.

The word kneye presents

some lexicographic difficulties. Several dictionaries have the word, though

spelling it differently in each case -- but never knie with ayin (or knie

with hey at the end for our first guess, relating the word to Hebrew liknos

'to buy'). Tsanin in his Fuler yidish-hebreisher verterbukh (Complete

Yiddish-Hebrew Dictionary [1982]) has di kneye (s) [kuf, nun tsvey yudn,

ayin] 'khor, ken, shakhat'. And on the same page he has the word kneye

(kuf nun ayin yud ayin) with the same meanings! Tsanin apparently regards the

two forms as legitimate variants, but neither is SA's spelling.

A dictionary compiled by Khana

Reicher [I don't know this dictionary] also gives both kuf, nun, tsvey yodn,

ayin -- and kuf, nun, ayin, yod, ayin both with virtually identical

definitions in Hebrew -- including 'lokh' and 'keyver'. shahat means grub

'grave'.

So my present interpretation is

that the yoyred Zisl is saying that his rich relative won't even give him a

hole in the earth in which to be buried. All three meanings offered for

this word make sense -- but until we know the etymology and see a few more

instances of its use we can't feel sure.

More recently Meyer uncovered a

second attestation of the word in a SA story. The following citation is

from Meshugoim, prefaced by its textual context:

The story is that Moyshe, from

the Land of the Royte Yidelekh (between the Sambatyon and the Harey Khoyshekh)

disappears one day. His townsfolk search all over for him without success, but

one day he suddenly reappears. Everyone wants to hear where he has been and

what he has seen. He decides to tell them all in a book, which he proceeds to

write -- in this way he won't have to begin over his story with every fresh

listener. It takes him months but finally the book is ready and droves crowd

his house eager to buy it. His shrewish (and much abused) wife is amazed at the

sudden income and yells at her husband that such opportunities as they are

momentarily enjoying don't happen everyday and he should be charging more. This

she expresses with a string of curses:

"Makes volt ikh zey farkoyft

azoy volvl di skhoyre! A knihe [kuf nun yud hey ayin] erd voltn zey bay mir

oysgeshlogn ot-a-do-o, oystsien voltn zey zikh far mayne oygn! ..."

I would translate as follows:

"You wouldn't catch me selling such merchandise so cheap! From me they'd

get a grave to drop into right here before my eyes!"

My guess

seems to fit the two attestations we have found -- but Yiddish is a language we

are all still learning and we need more information before reaching any firm

conclusion.

4)-----------------------------------------

Date: 30 January 2006

From: Haggai Rogani

Subject: Hebrew Poets on the Jewish-Arab Conflict

"Facing the Ruined Village":

Political

Positions on the Jewish-Arab Conflict

in Hebrew

Poetry, 1929-1967

Haggai

Rogani

Abstract [1]

This study sets out to examine

representations of the Jewish-Arab conflict in Hebrew poetry and to look at the

views expressed in it between 1929 and the Six Day War in 1967. The theoretical

chapter presents the theories of Theodor Adorno, Louis Althusser, Frederic

Jameson, and others on the relations between art, poetry included, and a given

historical, social and political reality, and the relations between art and

ideology. As these theories clarify, no work of art is unconnected to reality;

each and every work stems from an ideological grounding and comprises hidden

strata, parts of a political unconscious (a phenomenon prominent in the poetry

of Chaim Guri). The chapter also discusses the roles of poets, as artists and

intellectuals, within the social system of the structure of power/knowledge, as

described by Michel Foucault. One pertinent image here is that of the poet as

prophet, an image manifested in European and Hebrew poetry since the 19th

century (prophetic elements are clearly discernible in the work of Uri Zvi

Greenberg and Yehuda Amichai). In addition, attitudes towards the

"other" are scrutinized in relation to the thinking of Emmanuel

Levinas, according to whom it is the other who determines the identity of self,

while the "otherness" of the other, both proximate and distant,

places unlimited responsibility upon the self (this type of outlook is characteristic

of Avoth Yeshurun). The chapter draws, as well, on the thinking of Edward Said

and Homi Bhabha for its description of political and cultural relations between

'west' and 'east,' oppressor and oppressed in the colonial and post-colonial

context, whether these are unidirectional relations of subjection (of the kind

envisioned by Uri Zvi Greenberg) or a two-directional system of mutual

influences with hybrid outcomes (this type of outlook is characteristic of

Avoth Yeshurun). Finally, the post-national work of Benedict Anderson informs

the chapter's view of nation as an imagined community (as is characteristic of

Alterman, while the poems of Zach and Amichai imply a post-national position).

This discussion departs from the

basic assumption that the manifestation of political positions towards 'the

conflict' in Hebrew poetry does not, of necessity, turn it into 'political

poetry'. The Jewish-Arab conflict is portrayed as a personal affliction

affecting each of the poets, as it affects every person living in this country.

Its appearance in poetry is similar to that of any other theme arising out of

personal distress. Nevertheless, political positions bear significance both in

and of themselves, and relative to other positions in connection to whether they

serve or contradict hegemonic ideologies, whether they're enlisted into the

service of ethos, myths, narratives and configurations of discourse which are

suited to the forces in power, or whether on the contrary they offer new

observations, a different discourse or an 'alternarrative'.

Uri Zvi Greenberg (1896-1981): When he first arrived in Palestine he identified with the

Zionist labor movement, but began to grow away from it from as early on as the

twenties, taking a messianic, right-wing and racist turn. In his poem"נאום בן הדם / על ערב" ("The

words of a blood son / On the Arab", 1930) he described the shattering of

his belief, of the type which Said later characterized as orientalist, that

Arabs were the blood brothers of Jews ("Sister to our race here is

daughter of the Arab") and his discovery that he faced a ruthless enemy

collaborating with the British regime. While the labor movement held that

conquest of the land would be effected through its settlement, U.Z.G. called

for conquest by force: "The teachings of your teachers: a land is bought

with money./ You buy the field and stake it with a hoe [...] And I say: a land

is conquered with blood". ("אמת אחת ולא שתים" "One Truth not Two"). He called the

leaders of the Yishuv (the pre-state Jewish community) who support a policy of

restraint and concessions, "Sanballat", or "Flavius", after

historical figures of Jewish traitors. Due to these stands U.Z.G. was

'excommunicated' by the labor movement, and affiliated himself with the maximalist

section of the revisionist right-wing. In his poem "כד מטיא שעתא..." ("When the Time Cometh...", 1936), he

described his hopes for a messianic leader, straight out of The Revelation of

John in The New Testament. This leader-general, whose slogan is

"Double blood for blood! / Double fire for fire!" will lead the

people on a campaign of revenge and conquest.

In ספר העמודים (The Book of Pillars)

written over the 40's and the 50's, he outlined his political theory: the

regime should be a monarchy, not a democracy; its ministers should be

aristocracy, "Eminent among the people, not their elected",

unrestricted by the judicial ("פרק מספר מלכים" "A Chapter from the Book of Kings").

Following foundation of the state in 1948, U.Z.G., disappointed by its very

limited area and also, mainly, by the concession of the Old City of Jerusalem,

charged the leadership with lack of vision. He disbelieved the agreements

reached with the Arabs and states, in "Tall Tales of Peace Among

Nations" ("לבלוב עלי שלכת" "Budding Autumn Leaves") that "We will live by

our sword". He continued to dream of campaigns of conquest and of a

"Land of the Race" stretching from the Nile to the Euphrates ("פרקים בתורת המדינה" "Chapters in the Theory of State").

U.Z.G.'s position on Arabs was explicitly racist and hateful. Very frequently,

he assigned them de-humanizing and humiliating labels such as: "son of the

slave woman", "dogs of Arab", "dregs of Arab". In his

view, there were "Two kinds of people in this world: circumcised – uncircumcised"

("שיר העוגבר" "Song of the Pipe-Organ Player"), and

"None are purer-for-rule than the Jews" ("בירת הים התיכון" "Capital of the Mediterranean").

At the opposite pole, Avoth

Yeshurun (1903-1993) grew close to Arabs soon after emigrating to

Palestine, lived among them and learned their language. His series of poems "צום

וצמאון" ("Fasting and Thirst") written in the early thirties

is a romantic idyll of sorts about the lives of the local Bedouin, displaying

love and honor towards Arab culture and an identification with the

"other", to draw on the concept of the other presented by Levinas. In

the wake of 1948, Avoth Yeshurun expressed distress, responsibility and guilt

for the Palestinian catastrophe, likening their suffering to that of the Jews

in the Holocaust. In the poems "יום העז", "ראחת",

"דֶּבְּקָה" ("Day of the Goat", "She

Left", and "Debka", 1949) he expressed identification with the

Arab mother banished from her land along with her children, and in other poems

he painfully depicted the destruction of the Arab villages of the Khula Valley:

"we erased Yarda into tilled earth" ("אני ברחובי" "I on My Street"). In the poem "רְעֵם" ("Shepherd Them") he displayed concern

for Arab youth and a fear of their future revenge. In his well-known poem "פסח על כוכים" ("Passover Hovels", 1952) Yeshurun

protested the fatal blow to the Palestinians, whom he equated with both the

ancient Hebrew Patriarchs and his own father and mother. The deeds in question,

he claimed, contradict the humanist nature of Judaism, particularly in the wake

of the Holocaust: "and father-mother, in the taking / fire-to-multitude

when taking – / commanded us Jewness never forget / and Poland never

forget" (to paraphrase: when mother and father were taken to the ovens

they commanded us not to forget Judaism or the heritage of Poland). This poem

caused a heated debate and Yeshurun felt persecuted and shunned. Yeshurun's

poetic language, a combination of Hebrew, Arabic and Yiddish, was a hybrid

product of the type of inter-cultural encounter theorized by Homi Bhabha. His choice

to integrate Arabic forms was a pointedly political one, testifying to his

awareness of the "other" whose world and culture he visibly

respected.

The poetry of Alexander Penn

(1906-1972) too, as well as that of Mordechai Avi-Shaul (1898-1988),

expressed strong protest against the injuries inflicted upon Arabs. Penn

identified at first with the pioneering project and his early poems are imbued

with the spirit of contemporary Zionist myths ("Land my land […] I have

thee wed in blood", 1939). After joining Marxist circles he increasingly

expressed the dream of 'brotherhood among nations,' and attempted to forge an

a-national discourse of sorts. The myth of Isaac and Ishmael stressing the

close relationship between Jews and Arabs became a frequent motif in his poetry

("הגר" "Hagar", 1947, "בלדה על שלושים וחמישה" "A Ballad of Thirty-Five", 1948). His

dream, however, was shattered by the War of Independence. In two series of

poems about the destruction of Palestinian villages ("שירי עם", "מִזִמרת הארץ" "Folk Songs" and

"Airs of the Land", 1958) he protested the deeds of destruction and

lamented the Palestinian tragedy: "A voice rings out in Rammah, / Not

Rachel bitterly sobbing. / Land, oh land, / It is Hagar lamenting her

sons!…" In his poetry of the fifties, Avi-Shaul too voiced protest in the

spirit of both morality and the communist party: "My people! Hear! […] The

cry of injustice rolling". He cried out to warn his nation that it would

someday be called upon to pay the price before the seat of "international

solidarity". Discernible here is a phenomenon cautioned against by Adorno:

a poem’s total domination by protest, at the expense of artistic quality.

Nathan Alterman (1910-1970) is commonly placed at the heart of the Zionist labor

movement consensus. However, he emerges as a poet who expressed complex and

sometimes even subversive positions. His poetry reveals two characteristic

parallel lines: personal lyrical poems (such as those of כוכבים בחוץ, Outdoor Stars and שמחת עניים, Joy of the Poor) and topical polemic poems published in

the daily press (and collected, for the most part, in הטור השביעי, The Seventh Column). In his

topical poems of the forties, Alterman constructed the myth of the new Jewish

nation, born of the Holocaust and giving form to the Land of Israel, realizing,

as it were, Anderson's portrayal of nation as an imagined construct. The Ballad

"על הילד אברם" ("On the Boy Abram", 1946) tells of

a Jewish boy lying on the steps of his home after the Second World War,

refusing to get up and go to his bed, despite the pleas of his dead family

members and the nations of the world. Then he hears the voice of the Lord

telling him, "Go forth, through the night of knives and blood, / To the

land that I will show you". The poem "מגש הכסף" ("Silver Platter", December, 1947) was a

response to the U.N. decision to establish a Jewish state, expressing a fear of

the results of the pending war. In it, the nation is cast as an ancient goddess

demanding young human sacrifices. As the war ends, she prepares for the

ceremony awaiting a miracle, but is shocked when instead she sees two young

living-dead fighters, a woman and a man, marching towards her. She responds

aloofly, asking "Who are you?" and they introduce themselves

declaring "We are the silver platter / Upon which you have been given the

state of the Jews", then falling dead at her feet. The poem may express a

critical stand towards the Yishuv and its leaders, portraying their treatment

of the young Palmach fighters who sacrificed their lives for the nascent state

as distant and ungrateful.

Arabs were almost totally absent

from Alterman's first poems, which preserve and reinforce the Zionist ethos. In

"הורגי השדות" ("The Killers of Fields", 1936),

with its mythical atmosphere, the mountain dwellers sally out of their villages

by night and set fire to the fields. Both "עץ הזית" ("The Olive Tree") and "מערומי האש" ("Naked Fire"), (from Outdoor Stars,

1938) referred as well to the pioneers' struggle to put down roots in the land,

intimating the Arabs' existence like a Jungian shadow in the background, in the

metaphors "pure hatred" and "transparent wall of revenge".

At this point, there was no attempt to understand the "other", and

the animosity of the Arabs was represented as random and without reason. During

the War of Independence Alterman's stand gradually changed and he showed

increasing empathy towards the Arabs, in face of their catastrophe. In the

polemical poem "על זאת" ("Of This", 1948) he reacted to war crimes, protested

their cover-up and urged the punishment of those responsible. In the poem

series "מלחמת ערים" ("War of Cities") (עיר היונה, City of the Dove,

1957) he described the fall of the Palestinian city of Jaffa and the flight of

its residents in a manner that recalls representations of the tragedies of

Jewish refugees in the diaspora ("There the eyeless mass goes down /

Gathers at the foot of the mound / Shuffling and dragging crutches / Behind the

belongings it wheels along".). Following establishment of the state Alterman

criticized the government policy towards the Arab minority, and many of his

topical poems used sharp language to denounce injustices and injuries,

including the massacre at the village of Kafr Kassem (1956). He saw the Arab

citizens of Israel as "an oppressed and just minority", while to him

the Jewish majority had become "a collective of clubs and helmets" ("מהומות בנצרת", "Disruptions in Nazareth", 1958).

In the course of the War of

Independence a new generation of young soldier-poets arose, "the 1948

generation". Abba Kovner (1918-1987), expressed his enthusiastic

identification with the goals of the war in issues of the "דף קרבי" ("Combat Page"), a publication

distributed during the fighting among the soldiers of the brigade where he

served as information officer. In his long poem "פרידה מהדרום" ("A Parting from the South", 1949) he

displayed his shock at the burning of Palestinian communities and the damage

inflicted on civilians ( "שערי עיר""Gates of the City", "קולות מהגבעה" "Voices from the Hill"). He viewed the

horrors of war as "Guernica on every hilltop" ("אבן חלקה" "Smooth Stone"). This type of criticism

was nonexistent in the early poetry of Chaim Guri (b. 1923), which was

heroic and patriotic. In his war poetry (פרחי אש Fire Flowers, 1949 and עד עלות השחר Till Sunrise, 1950) he expressed the joy of

battle and his fascination with the sights of war ("בדרך באר שבע" "On the Way to Beer Sheva", "נצרת" "Nazareth"). He pledged his loyalty to comradeship

and the sword even after the battles end ("כַּאֲלֻמַּת חִטִּים" "Like a Sheaf of Wheat"). The comrades,

like the speaker himself, were handsome young men, their heads crowned with

curls, conforming to the Sabra stereotype, and Guri was one of the form-givers

of the poetry mourning the deaths of warriors, incorporating the myth of the

living-dead. The Palestinian inhabitants of the conquered cities were hardly

mentioned in his poems. Though aware of their suffering (as evidenced by his

war journal "דרך האש" "Path of Fire"), the author failed to

express any doubts about the justice of the deeds of war, in the poems he wrote

during this period. His identification with the goals of the war seems total,

and with it his apparent resignation to the suffering caused the other side. In

שירי חותם (Seal Poems, 1954)

another Guri emerged, haunted by regrets and guilt for what has been done to

the Palestinians. As this indicates, his justification of these deeds in the

earlier poems amounted to a repression of the contradiction between the poet's

humanist values and ideology and its practice. By now, his 'political

unconscious,' to employ Jameson's term, was exacting its price: "And every

night he returns from beyond, / The one I beat, / Whose well I made a grave /

Whose vineyard and home I took" ("שיר הנדרים והקורות" "Poem of Vows and Things

Past"). This also testifies to some degree of acknowledgement of

responsibility for the Palestinian tragedy.

Yehuda Amichai (1924-2000), though the same age as Guri, was usually included in a

later literary generation, 'the state generation' (or, more precisely: the

'Likrat' [towards] circle). He began his poetic trajectory as a soldier-poet

during the War of Independence, but his stands were distinctly pacifist: he

abhorred war and all it stood for, did not identify with its goals and rejected

the heroic symbols and myths associated with it. In the sonnets "אהבנו כאן" ("We Loved Here"[2],

1955) he drew an analogy between the War of Independence in which he fought and

the First World War in which his father fought: both felt a similar sense of

alienation towards the goals of these respective wars. The poem "גשם בשדה קרב" ("Rain in a Battlefield", 1955)

describes death in the battlefield as final and pointless, in contrast to the

symbolic heroism of the living-dead motif recurring throughout the poetry of

the 1948 generation. Clearly focused stands emerge through Amichai's poetry: he

opposed some of the basic assumptions of Zionist ideology, particularly as it

was realized in and after the War of Independence; he rejected the historical,

religious and mythological justifications of Zionism. Overall, Amichai rejected

the concept of nation as worth dying or killing for, thus expressing a

post-national viewpoint. He strongly opposed the tragic damage inflicted upon

the Palestinians, including killing, dislocation, the destruction of homes and

the annihilation of the social infrastructure. By the same token, he remained

equally unresigned to the heavy price in Israeli lives exacted by the War of

Independence and other acts of violence. Indication of this protest is evident

in quatrains 37, 38, 39 from "בזוית ישרה"

("In a Right Angle", 1963). The plot line that gradually arises from

the conceit is one of forced exile, massacre, the appropriations of homes and

the silencing of these deeds: "One who thought and smiled and one who

cried and tried […] one who slaughtered and blessed and one who stayed silent

and covered up".

Amichai

viewed the poet as an observer entrusted with a mission, a prophet of sorts,

who always "stands beside the window. / He must see the evil among thorns

/ And the fires on the hill" (""משלושה או ארבעה בחדר

"Of Three or Four in A Room", 1958)[3]. In "אלגיה על כפר נטוש" ("Elegy on an

Abandoned Village", 1963)[4] the speaker facing an

abandoned Arab village suddenly experiences a revelation, as it were, and the

village fills up with voices and scenes: first the ululating of the women, then

the children's voices. Birds are transformed into children before his eyes, and

fig trees into girls. All this is apparently triggered by the speaker's sorrow

and his feelings of guilt for the destruction. The prophetic poem "המקום שבו אנו צודקים" ("The Place Where We

Are Right", 1959)[5] confronts 'our'

justice with the values of morality and humanity. Justice is personified in a

violent masculine figure, and the ground under his feet is "trampled and

hard / like a court", a simile with intertextual links to the prophecy of

rage in Isaiah 1: 12, directed at the people's sinful leaders: "who

requires of you trampling of my courts?" From the trampled earth

"Flowers will never grow / In the spring". Contradicting the Zionist

myth of making the desert bloom, the poem portrays the conquest of the land as

an ecological disaster. The poem's closing lines are "And a whisper will

be heard in the place / Where the ruined / House once stood". Since 1948

the destroyed home in collective Israeli consciousness has been not only the

Temple but also the Palestinian home. Perhaps the whisper expresses the guilt

seeping up to the surface through the collective unconscious.

A post-national (and indeed

post-Zionist) stand is also visible in the poetry of Nathan Zach (b.

1930), the foremost spokesman of the 'Likrat' circle. In his allegorical poem "לחוף ימים" ("On the Shore", 1955) Zionism is

represented as a failing colonialist adventure: The settlers find themselves in

the foreign land, bewildered, with no sense of belonging to locale and fearful

of the "desert tribes." The poem "אלה מסעֵי" ("The Travels of", 1960) predicts that

the "savages" will dance upon the ruins of the kingdom.

As this discussion demonstrates,

where the Jewish-Arab conflict is concerned, Hebrew poetry doesn't bend to the

hegemonic ideologies or patterns of discourse. At times it is even a true

poetry of dissent. Most of the poets examined in this discussion stood their

ground valiantly, though it fell outside of majority consensus. Some of them

paid very dearly. This was distinctly so for Greenberg on the right and for

Yeshurun and Penn on the left. Amichai's poetry too, however, revealed a clear subversive

aspect. Even Alterman, usually firmly identified with administration positions,

expressed both criticism and protest on these issues through his poetry. While

it stopped short at openly questioning the consensus, the political unconscious

of Guri's poetry testified to a sharp contradiction between the poet's humanist

outlook and the need to tow the ideological line. The various conflicts are

represented as instances of personal distress, rather than political issues,

and the reasons for dissent are accordingly related to the poets' distress: a

shattered dream (Greenberg) or a contradiction between dominant ideology and

praxis and the individual's humanist values and beliefs (the rest of the poets

above). This study could be said, then, to argue in defense of Hebrew poetry,

that it did itself proud in the mission it undertook within the structure of

power and knowledge in Israeli society. It

examined reality fearlessly and expressed the internal truth of each and

every poet vis a vis this reality, re-examining the central ethos,

dismantling myths, and even proposing new knowledge towards forming another

ethos, other forms of discourse and other narratives.

[1]

Translated by Rela Mazali including poetry fragments and titles unless

otherwise indicated.

[2]

Amichai, Yehuda (1996). The Selected Poetry of Yehuda Amichai (Chana Bloch and Stephen Mitchell, trs.). Berkeley:

University of California Press, p. 8.

[3]

Ibid, p. 12.

[4]

Ibid, p. 42.

[5]

Ibid, p. 34.

5)----------------------------------------

Coming Issues: Artists'

Portraits of Yiddish Writers presented by David Mazower.

The graphic dimension of Yiddish

literature, specifically portraiture by recognized painters of Yiddish authors

(as distinct from, say, book illustration and design) is a special interest of

David Mazower within the larger boundaries of Jewish art. The next issue of TMR

will carry the first of a series of illustrated commentaries on this

relatively unexplored field.

----------------------------------------

End of The Mendele Review Vol.

10.01

Editor, Leonard Prager

Subscribers to

Mendele (see below) automatically receive The Mendele Review.

Send "to

subscribe" or change-of-status messages to: listproc@lists.yale.edu

a. For a temporary stop: set mendele mail postpone

b. To resume delivery: set mendele

mail ack

c. To subscribe: sub mendele

first_name last_name

d. To unsubscribe kholile: unsub

mendele

****Getting

back issues****

The

Mendele Review archives can be

reached at: http://yiddish.haifa.ac.il/tmr/tmr.htm

Yiddish

Theatre Forum archives can be reached

at: http://yiddish.haifa.ac.il/tmr/ytf/ytf.htm

***