The Mendele Review: Yiddish Literature

and Language

(A Companion to MENDELE)

-----------------------------------------------------------------

Contents

of Vol. 09.08 [Sequential No. 160]

Date:

1) This issue. (ed.)

2) A Review of Menke: The Complete

Yiddish Poems (ed.)

http://yiddish.haifa.ac.il/tmr/tmr09/tmr09008.htm

1)---------------------------------------------------

Date:

From: Leonard Prager, ed.

Subject: This issue.

This

issue of TMR is devoted to Menke,

translations by Benjamin and Barbara Harshav of the

Yiddish poems of the bilingual poet Menke Katz

(1906-1991) with a monographic introduction by the poet's son Dovid Katz. The poems are described in general terms,

briefly illustrated, and a central issue of the Introduction is discussed.

2)-------------------------------------------------------------

Date:

From: Leonard Prager

Subject: A Review of Menke:

The Complete Yiddish Poems

Menke; The Complete Yiddish Poems of Menke

Katz, translated by Benjamin

and Barbara Harshav, Edited by Dovid

Katz and Harry Smith.

A

Substantial Volume

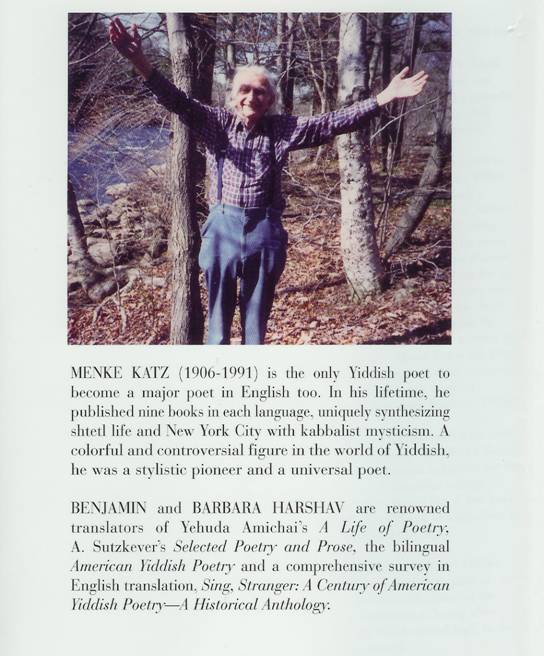

Menke

richly portrays the life of the exuberant Menke Katz

(1906-1991), one of the few Yiddish poets in America who published in English

(appearing in Atlantic, New York Times, Poet Lore , Poetry,

Prairie Schooner and elsewhere).

The main body of Menke's 779 pages

provides English translations by Benjamin and Barbara Harshav

of virtually the entire published corpus of Menke

Katz's Yiddish verse. To contextualize this mass of poems and illuminate the period, the

milieu, the familial and personal background, the poet's son, Dovid Katz, has written a comprehensive 122-page

biographical, critical and personal introduction. There is also a preface from

publisher Harry Smith, a lifelong friend and collaborator of the poet and an

intriguing free spirit in his own right.

Smith and Katz edited the book, reviewing "every line

together" (p. xi) and the translators worked on the poems "over a

period covering most of the 1990s" (p. xi).

Family

Saga, Epic of Places and Ode to Yiddish

Menke

is a family saga: "I love so

much my mother's hearty laughter." (p.531)

"Father, in that old house of yours, you became a legend of Svir. We five children are hushed in fear of your quieted

voice." (p. 552) "Rivke,

radiant girl of the gray

Menke

is an epic of places, a kind of versified yisker-bukh

(memorial book), especially of the magical shtetl

of Michaleshik (now in

Bridging

epic and saga, Menke is an impassioned ode to

Yiddish, to yidish koydesh,

a central leitmotif in the poet's entire work and title of a group of poems in

the volume from the 1947 Der posheter kholem (The Simple

Dream). Here in a poem called "Michaleshik"

we meet the poet's fervent belief in the power of Yiddish to resurrect itself. The poem ends on the line: "Mit

ale kheynen fun mame-loshn,

veln dikh nokh kinderlekh tseshaynen." (p. 37) (With all the charms of mame-loshn, babies will shine upon you one

day.) (p. 490) A

late poem entitled "Yiddish" begins "Mother, in what language

does the brook chatter?" (p. 754) And in

"Yiddish at

O

Michaleshik, O Svintsyan

àÕó

îÖÇï îöáä

.. 1906-19

áøéãòø, ùÔòñèòø îÖÇðòÓ

ãàÈ ÔåÌ ééÄãéù ùèåîè,

Ôé àÈè ãòø ùèÕá ôÏåï îÖÇï ÷áø,

ãàÈøè äàÈá àéê ÷Öï îàÈì ðéè

âòìòáè.

ãàÈ

ÔåÌ ééÄãéù ÔÖðè,

Ôé ãé àÇù ôÏåï îÖÇðò ùèòèòìòê

–

àÕ, îéëàÇìéùò÷, àÕ, ñÔéðöéàÇï,

–

ãàÈøè ÔÖðè îÖÇï èàÇèò àåï îÖÇï îàÇîò,

ãàÈøè äòø àéê ÷Öï îàÈì ðéè àÕó ÔÖðòï.

ãàÈ

ÔåÌ ééÄãéù ìàÇëè,

äàÈôÏòøãé÷, Ôé ôÏøéìéðâãé÷òø

Ôéðè,

ãàÈøè ìàÇëè îÖÇï èàÇèò àåï îÖÇï îàÇîò,

ãàÈøè äòø àéê ÷Öï îàÈì ðéè àÕó ìàÇëï,

ãàÈøè äòøï îéø ÷Öï îàÈì ðéè àÕó ìòáï.

On

My Gravestone

1906-19..

Brothers,

sisters of mine:

In the place where Yiddish is mute,

As this very dust of my grave,

There I have never lived.

In

the place where Yiddish weeps,

As the ash of my villages –

O Michaleshik, O Svintsyan,

–

There my father and mother weep.

In

the place where Yiddish laughs,

Sanguine as spring's wind,

There my father and mother laugh,

There I never stop laughing

There we never stop living.

îùéç

àéê

ÔÖñ èàÇèò, îùéç Ôòè ÷åîòï

ôÏåï îéëàÇìéùò÷,

Ôòè àÕó àÇï àÖæòìò øÖÇèï ãåøê ñÔéø àåï ãåøê ñÔéðöéàÇï,

ãàÈøè ÔåÌ ãé äÖìé÷ñèò òøã àÕó ãòø Ôòìè

àéæ ôÏàÇøàÇï,

àéê ÔÖñ îàÇîò, îùéç Ôòè ÷åîòï

ôÏåï îéëàÇìéùò÷,

ÔÖÇì àéï âï-òãï âòáìéáï

àéæ îéëàÇìéùò÷

àåï îéè ãé ÔàÈøöìòï àéáòøâò÷òøè ìéâè àéï äéîì ñÔéðöéàÇï.

ãàÈøè ÔåÌ ãé áòð÷ùàÇôÏè àéæ

Ôé âàÈè, àÈï àÇï àÈðäÖá,

àÈï àÇ áøòâ

Ôòè îùéç ÷åîòï, àÕ, îéëàÇìéùò÷,

àÕ ñÔéø, àÕ, ñÔéðöéàÇï.

Messiah

I

know, father, Messiah will come from Michaleshik.

Riding a donkey through Svir and Svintsyan,

Where there is the holiest soil in the world.

I know, mother, Messiah will come from Michaleshik,

For Michaleshik stayed in the Garden of Eden,

And with roots upside down, Svintsyan lies in heaven.

Where

longing is like God, with no beginning, no end,

Messiah will come, O Michaleshik, O Svintsyan. (p.

736)

Father

and Son

The

intimate connection between poet - father and Yiddish scholar/writer – son that

underlies this entire work is cemented by a common devotion to Yiddish as shown

in the dedication to Tsfas ('Safed')

[Tel-Aviv, 1979]: "Far mayn zun

Hirshe-Dovid velkher iz in der ershter

rey, tsvishn di getrayste kemfer

far yidish." (For my son Hirshe-Dovid

who is in the first rank of the most faithful fighters for Yiddish.)

This

is a pristine instance of that highly esteemed and singularly Jewish mode of

pleasure known as "shepn nakhes

fun kinder." As accurately englished in Uriel Weinreich's MEYYED, the

emotion involved is 'proud pleasure'. With the exception of Agnon's

daughter Emunah Yaron, no

other child of a Jewish author that I can think of has devoted as much time and

energy to the posthumous publication of a writer-parent as has Dovid Katz.

The

poetry of filial piety is a substantial sub-genre in Yiddish poetry - one

thinks of Khayim Grade's moving poems to his mother and

Avrom-Nokhem Shtensl's to

his father. In Menke we have many poems of a

son to his father Heershe-Dovid, and his mother Badonna (Dovid Katz's grandfather

and grandmother). In "My Father on May Day," the third section of

"My Father Heershe-Dovid" in the volume Dawning

Man we have a typical Menke poem of the thirties

where filial feeling and social awareness fuse in free verse that works largely

through its images:

Facing

him –

Hands

from digging, chopping, turning, pushing –

Masons of cities, harbingers of storm

Through narrow alleys, through lands of steel.

Today

the streets, the bridges, the sky-ladder towers

Recognize their bosses.

Like

the sun, the route of the endless march

Cuts the day into blazing roads.

Unrest,

stinging under nails,

Like shrapnel in the hungry blood

The mood is bright and strong –

Seas tearing away from their shores.

My

father is dark, dark, through the dazzle of banners,

His bare flesh weeping through the tatters.

He

grows gray with the rust of silenced wheels.

Swinging idly, his hands

Leave traces of nails in his slim body.

(p. 73)

Dovid

Katz, who often writes under the name Heershe-Dovid

Katz, has not offered a poem to his father in this volume, but has edited Menke with its lengthy introduction that aspires to

be a history of the Yiddish literary world of

Apologia

The

translators of Menke Katz's poems speak through their

craft and make no claims for their author or their English renditions of his

work, which are "clean" and honest, yielding the plain sense of the

original and much of its sound and spirit. The editors on the other hand make

very considerable claims in the hope that an allegedly restricted Yiddish

literary canon will now make place for a figure neglected for political reasons.

Smith

writes:

"The

We

are given numerous instances where the poet stood up to Party browbeaters, but

he never broke with them, never moved to the camp of the "Rekhte" (Rightists). In one surely difficult period,

the poet, gritting his teeth or perhaps momentarily dreaming, appended to the talismanic place names "Michaleshik" and "Svintsian"

-- names repeated again and again through a lifetime of verse-making -- the

deeply political and subsequently emotive word "sovetishe":

"a gut morgn aykh: sovetishe shtetelekh mayne – Michalishek, Svintsyan!" ('good morning to

you, my Soviet towns, Michalishek, Svintsyan!' [p. 5]).

The

dreary diurnal imagery suits this "press poem," a term that Dovid Katz employs to cover this embarrassing subject. He

writes: "The rest of To Tell it in Happiness, largely comprising

press poems expressing relief at the occupation of (then)

The

"Yiddish Communists"

"It

was in the Jewish community that the Communists encountered their most serious

troubles during the time of the Hitler-Stalin pact…. those who presented

themselves as Jewish communists, writing and speaking in Yiddish and

appealing to a distinctive Jewish consciousness, suffered the greatest

emotional turmoil within themselves, met with the most violent criticism from

the anti-Communist Yiddish press, and soon began to drop out of the movement in

considerable numbers. Ever since the twenties the party had enjoyed a devoted

following among the Jewish garment workers. During the thirties it had won the

friendship of important Jewish intellectuals and established itself as a force

within Yiddish cultural life." (The American Communist Party

by Irving Howe and Lewis Coser, New York, 1974, p. 401)

"At

first the Freiheit, the Yiddish

Communist daily, claimed there was nothing necessarily wrong with the

non-aggression pacts and that, in any case, they did not conflict with the

anti-fascist Popular Front line. This

justification quickly became obsolete…. Once

Howe

and Coser tell us that "the hard core of

Yiddish-speaking Communists remained faithful…. The will to believe, the

necessity for faith, ran deep among them; the emotional investments of a

lifetime could not so easily be abandoned; and always there remained the hope

that somehow the

The

son would like to justify the father's political affiliation, which he sees as

the chief cause of the poet's exclusion from the "canon." He finally

asks him why he stayed so long in the Stalinist camp. "Why didn't Menke just pick himself up and take the proverbial walk

from 35 East 12th Street (the old Frayhayt

address) to 175 East Broadway (the Forverts),

and have it over and done with? This was

a painful question for him in later years, but his answer was… not couched in

any kind of heroics. The Linke had

provided him with a magnificent environment of writers, friends and literary

inspiration; they had published his poems and his books, they had given him a

Yiddish teacher's education and made him into a teacher in their Yiddish

schools. They had given him a life in

Anti-Zionist

Daubings

"From

1959 to 1960, Menke and Rivke

spent another year in

Katz has here exaggerated –

as he often does in other realms as well – as regards the complex and thorny

subject of the fate of Yiddish in

Sakhakl

(Summation)

Dovid

Katz develops the notion that allegiance to "right" or

"left" in the Yiddish-language world of New York's left-of-center

Jewry in the first half of the twentieth century was accidental and

ideologically of little import. He further draws this world as a genial

debating society, an extended New England Town Hall Meeting, as American as

apple-pie. He intimates that the bogeyman of "political correctness"

prevents us from seeing the virtues of the Frayhayt

and the Linke. This reader cannot agree that

the latter were some sort of debating society, or that they were notably

"American."

Menke

could have been a slimmer, more

selective volume, Yiddish original facing each translation. The introduction

gives much factual information about the remarkable Katz family and its central

figure, Menke, but endless paragraphs of reviewer's

comments do not make the book more readable. I have never believed that Menke and other Proletpen figures

were treated unjustly by the leading Yiddish writers of his day, but the

subject deserves continued study. Addition

of an index to this volume would earn the gratitude of students of American

Yiddish poetry. These students and many who do not read Yiddish will welcome

this new addition to the growing library of quality English translations of

Yiddish writing. The doughty translators Benjamin and Barbara Harshav and the editors Harry Smith and Dovid

Katz merit a yasher koyekh

('well done').

-----------------------------------------------

End of The Mendele Review Vol.09.08

Editor, Leonard Prager

Subscribers

to Mendele (see below) automatically receive The Mendele Review and the Yiddish Theatre Forum.

Send

"to subscribe" or change-of-status messages to: listproc@lists.yale.edu

1.

For

a temporary stop: set mendele mail postpone

2.

To

resume delivery: set mendele mail ack

3.

To

subscribe: sub mendele first_name

last_name

4.

To

unsubscribe kholile: unsub mendele

****Getting back issues****

The Mendele Review archives can be reached at: http://yiddish.haifa.ac.il/tmr/tmr.htm

Yiddish Theatre Forum archives can be reached at: http://yiddish.haifa.ac.il/tmr/ytf/ytf.htm