The Mendele

Review: Yiddish Literature and Language

(A Companion to MENDELE)

---------------------------------------------------------

Contents of Vol. 11.007 [Sequential No. 184]

Date:

1) This issue of TMR (ed). ***Shirley

Kumove wins prize. ***The Bergelson

explosion.

2) Dovid Bergelson's

"Bay nakht" translated by Leonard Prager [Yiddish text and audio:

http://yiddish.haifa.ac.il/Stories.html]

3) Towards a Reading of Dovid Bergelson's

"Bay nakht" (ed.)

4) Books and Journals Received: Yeled shel stav***Afn shvel ***All

My Young Years ***Lebns-fragn

5) Takones fun yidishn

oysleyg – copies still available

6) Gilgulim ('Metamorphoses'), Paris

(2008- )

7) Ralph Ellison and Yiddish (ed.)

Click here to enter:

http://yiddish.haifa.ac.il/tmr/tmr11/tmr11007.htm

1)----------------------------------------------------------

Date:

From: ed.

Subject: This issue of TMR.

*** Shirley Kumove, author

of several fine books of Yiddish proverbs and of translations from Yiddish has

been awarded the 2007 Helen and Stan Viner Canadian

Jewish Book Award for Yiddish Translation for her Drunk from the

Bitter Truth: The Poems of Anna Margolin. The

award took place on

While

scrolling the story you can hear Sarah Retter reading

it. You can also examine my translation in this issue of TMR and compare it

with Neugroschel's at http:/www/ibiblio.org/Yiddish/Book/Neugroschel2/jn-fantasy-night.html.

Lastly

you can read my tentative comments on what the story is "saying."

There

appears to be a Bergelson revival. In Israel Sifriat Poalim has reissued Dov-Ber Malkin's 2-vol. Ktavim (Writings) of 1962. A review of this book in HaAretz of 27.6.02 by the poet and reviewer Dror Burshteyn starts out with

the exhilarated sentence: "Eyze sofer nifla David Bergelson" (What a wonderful writer David Bergelson is!) Joseph Sherman and Gennady Estraich are the editors of now available David Bergelson (1884-1952): From Modernism to Socialist Realism

(

2)----------------------------------------------------------

Date:

From: Leonard Prager

Subject: David Bergelson's "Bay nakht"

(At Night) translated into

English [see too Joachim Neugroschels' translation

at

http://www.ibiblio.org/yiddish/Book/Neugroschel2/jn-fantasy-night.html]

At Night

by David Bergelson [Dovid Berglson]

tr. Leonard Prager

At night, once, in a dark, close-packed and hard-snoring

coach I suddenly awoke and spotted him sitting on the bench opposite. I

recognized him right off – it was the old familiar Night Jew who could never

sleep when he rode the trains at night. And not being able to sleep he grew

restless and searched about him for something, looking into everyone's eyes,

silently summoning some deep accounting.

"Young man," he turned his sad, tearful eyes

towards me, "where are you going?" His acerbic and ancient voice

echoed in my ears, a voice older than any time I could recall. He did not talk

to me again, yet it seemed as though his voice emitted not from him but from

some distant and somehow demanding place.

"Young man, where are you going,

young man?"

And, when I opened my eyes a second time in the dark

hard-snoring coach, the train was still speeding over black bogs and desolate

soggy fields, the raintears through the night beating

on the windows and in the far corner of the coach a lamp continuously

flickering and going out. Opposite the thin door that opened to a second part

of the coach a swaddled baby did not stop wailing. And here near the wakeful

Night Jew on the bench across from me there already sat a red-cheeked young man

in a jacket and boots and I somehow felt that I also knew him from the past. He

would rise from his accustomed seat whenever he was reminded of some accident

which had befallen him and there were always people around him ready to listen

to what he had to say. They regarded him with pity and said nothing. But while

they looked at him with pity and were silent, they saw that he had a kindly

nature and said to him, "Young man," they said to him, "would

you please hop down and boil us a kettle of tea."

The young man had by now related to the Night Jew all the

troubles of his life: "And that is why I cannot sleep," he quietly

remonstrated. "And what does one do," he asked the Night Jew,"

what does one do on such a long night?" "What does one do?" The

bored Night Jew did not understand: "What do you mean, what does one

do?" He looked long into the red-cheeked youth's eyes as though searching

for some deep response. "What does one do?" he repeated quietly, his

voice again monotonous, acerbic and ancient, older than any time I could

remember. "Look into a book," he said, "study...."

"But I cannot," the youth complained.

"Cannot?"

The Night Jew thought a while. "If you cannot, then

repeat after me, word for word. Repeat: 'In the beginning the earth was empty

and void, and darkness was on the face of the deep and the spirit of God

hovered over the waters.'" "In the beginning," the youth

repeated, "the earth was empty and void, and darkness was on the face of

the deep and the spirit of God hovered over the waters."

All about them the heavily chugging train with darkened

coach was full of the snoring and harsh breathing of those who, in the light of

the flickering lamp, slept in three registers, one higher than the next. Sweaty

faces turned red, swelled, cheeks blew out, noses piped -- and all these in

three different modes. One sound was steady, decent, innocent, as though it

wanted to say, "Well, yes, I am sleeping... obviously I am asleep."

Another volley was depressed and listless: "I sleep because the world is

chaotic..." A cyclical piping, a

kind of rise and sudden fall as in the biblical "tebir"

cantillation seemed to ask, "What then is going

to happen here when everyone is asleep, then what will we have here?" And

a yet stronger sound that did not want to listen to anybody warned, "Don't

wake anyone, it will be of no use."

And in the midst of all that snoring and harsh breathing,

the red-cheeked youth repeated word for word what the restless Night Jew had

recited, how God created heaven and earth, sun and stars, day and night,

reptiles and mammals, birds, grasses and people, how the serpent was cunning

and how the wrongdoing of people had grown, and God regretted he had created

humans. God said: "I will sweep off the earth all creatures, from the

humans I created to the reptiles and birds that fly in the heights, for I

regret having created them." And suddenly... suddenly there arose out of

the ennui-suffering Night Jew a certain person called Noah. "Repeat after me,

word for word," he said to the red-cheeked youth. Repeat:" 'And Noah

found favor in the eyes of God.'"

"And Noah," repeated the youth, "found favor in the

eyes of God." All around, the hard snoring went on. The train continued

across black bogs and desolate water-drenched fields. And the night kept on

beating raintears on the windows. The only ones not

yet asleep were myself, the bored Night Jew and the

red-cheeked youth in the jacket and boots. The Night Jew and the youth sat as

though congealed, looking into each other's faces and I lay and thought:

"A good word: 'and Noah found favor'. It had saved the world."

Copyright

2007

Leonard Prager

3)----------------------------------------------

Date:

From: Leonard Prager

Subject: Towards A Reading of Dovid Bergelson's "Bay nakht"(ed.)

Variant

understandings of a work of literature can illuminate one another and make for lively discussion. Bergelson's "At Night" is singularly ambiguous

and lends itself to the most varied readings. My own view of the story is at this stage tentative,

unfixed. Let me begin by mentioning a matter which is omitted in most reprintings of the story. I suspect that the piece first

appeared in the rich January 1916 issue of

I

do not find

mystical, mythological or religious elements in this very secular allegory.

"At Night" is a symbolic fable that unravels on both a realistic and

a surrealistic level. We are aboard a real train in inclement weather in an

unspecified region at an undefined time with a diverse company of passengers

and heading we know not where. The key element in this railroad story is a

transparent metaphorical question which is repeated by a character known as

Night Jew and addressed to Young Man in Jacket and Boots: "Where are you

going?" Given that the author is David Bergelson,

the year 1916 (or earlier), it is reasonable to gloss this queston

as dealing with the direction of young assimilated Jewish youth who have left

their parents' world and not found themselves in the larger Russian one, a

generation which has severed itself from a rich Past but faces an uncertain

Future. The question of direction also applies to the teller who is the

author's persona. It is not the "story" that creates the total

impression of this somewhat strange and Kafkaesque narrative, as it is the sum

of all the verbal repetitions whose effect is hypnotic.

Ordinary life is experienced in such actions as making tea

for others and such non-actions as failing to comfort a swaddling infant who

does not stop crying. The hoary and sad Night Jew tries to redeem Young Man

with Jacket and Boots by an improvised Jewish catechetics,

rote repetition starting from the very first words of Genesis. They represent

the most fundamental text of Jewish civilization. By the story's end the pair

has reached the story of Noah and the Flood. At the tale's close, the two main

characters, Night Jew and Young Man in Jacket and Boots stare at one another in

congealed blankness.

The

teller, who may be largely the author himself, is the one who observes the contrast

between the cacophony of the snoring and the recitation of Torah passages. This

recitation is somewhat astounding since it can only be begun and hardly can go

very far; yet there is bravery here as well as hopelessness. Neither the Night

Jew nor the Red-Cheeked Youth in Jacket and Boots is idealized – both are

somehow familiar to the teller from the Past. They may have appeared in dreams

and are returning in this "halb-getrakhte mayse". Nor is the "public", whose single

attractive sign is to evince sympathy for the youth, a positive force. Their

three (I count four) modes of snoring represent the gamut of ordinary troubled

mankind.

Passages

from the biblical book of Genesis – the creation myth and the story of Noah and

the Flood -- are surely significant. The very last words of the story refer to

Noah, a righteous man who found favor in God's eyes. "Found favor" to

the teller is a powerful expression, Noah's finding favor having "saved

the world." The teller may indeed believe that Noah "saved the world"

– alluding to God's promise not to flood the world a second time. But can we

believe that Dovid Berglson

saw matters in this light?

The

rabbis had difficulties describing Noah as an exemplary figure, stressing that

he was only virtuous relative to his contemporaries. The modern reader has

numerous difficulties with the image of the virtuous hero who saved the world

from a second inundation. When God informed Noah of his plan to save him and

his family on the

4)

------------------------------------------------------------

Date:

From: ed.

Subject: Books and Journals Received (ed.)

Yeled shel stav [A Child of

Autumn] by Sholem Ash [Shalom Asch]

stories translated into Hebrew by Leah Ayalon;

illustrations by Rita Zlubinski. Kibbutz Dahlia:

"Ma'arekhet", 2007. This is the first

translation of a body of Sholem Ash's largely unknown

short stories into Hebrew in many years. The translator received a doctorate

from the University of Haifa for her close study of Ash's Der

man fun natsres (The Nazarene). The new

collection may be purchased from Bet Shalom Ash c/o Shura

Turkov at

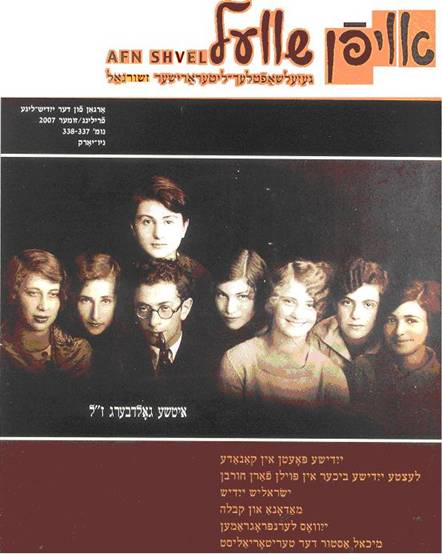

-- Afn shvel; gezelshhaftlekh-literarisher

zhurnal. Summer 2007, No. 337-338

The new Afn shvel under the editorship of Sheva

Tsuker has a bright and inviting appearance. A

contemporary journal in Yiddish, it should now be attractive to a wider

audience, old and young, in

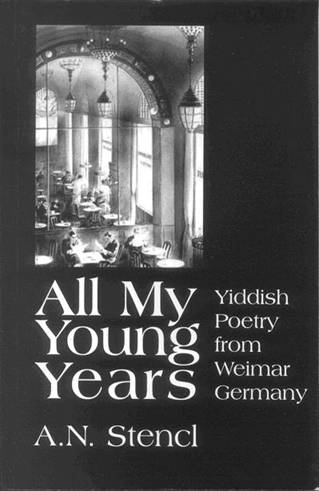

-- All My Young Years; Yiddish Poetry from

An impressive bilingual (Yiddish and English) A.N. Stencl

[Avrom-Nokhem Shtentsl]

volume has now appeared, appropriately dedicated to the memory of Majer Bogdanski (1912-2005), a

sterling personality who continued the Stencl

tradition in London's East End after the

poet's death in 1983. Heather Valencia in her introduction gives us the

best portrait of Shtentsl that has appeared anywhere.

The poems selected are from Shtentsl's early – and

arguably best work – very ably translated by Haike Beruriah Wiegand and Stephen

Watts. While several major Yiddish writers were for longer or shorter periods

domiciled in

-- LebnsÎ fragn; sotsialistishe

khoydeshÎshrift far politik, gezelshaft un kultur. Nos. 655-656

[May-June 2007]

Yitskhok Luden bravely continues to edit this veteran journal, which

now has an easy-to read

internet version. In the most recent issue the editor unleashes

his disapproval of young non-native speakers who are "purists" and

proscribe many old Yiddish words as "daytshmerish".

5)--------------------------------------------------------------

Date:

From: League for Yiddish, Inc.

Subject: Takones fun yidishn

oysleyg – copies still available

Der EynhaytlekherYidisher

Oysleyg: Takones fun Yidishn Oysleyg. Zekster aroyskum,

in eynem mit Mordkhe Shekhters "Fun Folkshprakh tsu Kulturshprakh." [The Standardized

Yiddish Orthography. Sixth edition, together with Mordkhe Schaechter’s "Fun

Folkshprakh tsu Kulturshprakh" (The History of the Standardized

Yiddish Spelling)].

6)-------------------------------------------------------------

Date:

From: ed.

Subject: Gilgulim ('Metamorphoses')

A new literary

journal in Yiddish has been announced. This is a cheering event in the world of

Yiddish. The address is c/o M. Gilles Rozier , 102 Boulevard Voltaire 75011 Paris

7)-------------------------------------------------

Date:

From: ed.

Subject: Ralph Ellison and Yiddish (ed.)

In his review of Arnold Rampersad's Ralph

Ellison: a Biography in a recent New Republic Online,

Christopher Benfey writes: "One of Rampersad's

surprising revelations is that Ellison had a comfortable command of Yiddish,

having picked it up, apparently, from clients of his mother's in

------------------------------------------

End of The Mendele Review Vol. 11.007

Editor, Leonard

Prager

Subscribers to Mendele

(see below) automatically receive The Mendele

Review.

Send "to subscribe" or change-of-status messages

to: listproc@lists.yale.edu

a. For a temporary stop: set mendele

mail postpone

b. To resume

delivery: set mendele mail ack

c. To

subscribe: sub mendele first_name

last_name

d. To

unsubscribe kholile: unsub mendele

*** Getting back issues ***

The Mendele

Review archives can be

reached at: http://yiddish.haifa.ac.il/tmr/tmr.htm

Yiddish Theatre Forum archives can be reached at: http://yiddish.haifa.ac.il/tmr/ytf/ytf.htm

Mendele on the web: http://shakti.trincoll.edu/~mendele/index.utf-8.htm

***