The Mendele Review: Yiddish

Literature and Language

(A Companion to MENDELE)

---------------------------------------------------------

Contents of Vol. 10.006 [Sequential No. 171]

Date:

A Salute to the

1) This issue of TMR (ed.)

2) Selections from Seyfer Lutsk ('Lutsk/Luck

Memorial Volume')

(a) "Eygn blut"

("One's Own Flesh and Blood") by Yoyl Perel

(b) "Vitold Fomienko -- Mayn Reter" ('Witold Fomienko

-- My Rescuer') by Shoshana Yakubovitsh

3) Artists' Portraits of Yiddish Writers, 3rd

Series / Irma Stern and Alva (David Mazower)

Click

here to enter: http://yiddish.haifa.ac.il/tmr/tmr10/tmr10006.htm

1)---------------------------------------------------

Date:

From: ed.

Subject: This issue of TMR

We salute the New York Public Library for

its magnificent gift to the public -- a comprehensive digitized library of 650+ yisker-bikher ('Memorial Books')

accessible on the internet the world over, and the

This issue of TMR presents a miniscule

selection -- merely two items -- from a single volume in what is a vast

cybernetic collection. Because of my role (together with Lucas Bruyn) in

translating and editing an essay on Lutsk/Luck (see Geven a shtot lutsk), many persons with family connection to

that city have queried me about particulars that only a genuine

resident could answer. I bring no new tidings regarding the wealth of

historical, literary, folkloristic and other kinds of values with

which massive yisker tomes such as Seyfer Lutsk are full. The two selections I have chosen

and which I give both in their original Yiddish and in English translation,

struck me in particular. It is overwhelming to consider that the memorial

literature of the Shoa, a large proportion by untrained writers, is dense

with such powerful narratives. We will never fathom the full horrors of the

Shoa, but we can avoid a coldly statistical approach by listening to

individual narrators relating their own experiences. Bashe's heart-rending

story as perceived by Yoyl Perel (about whom, incidentally I as yet know

nothing) documents the reverberations of a "normal" Polish-Jewish

domestic tragedy under the extreme and unsupportable pressures of the Shoa.

The teller's description of the Ukrainian squatters

as both fearful and insolent corroborates Jan T. Gross's view of Polish

post-Holocaust antisemitism as a special case (see his recent Fear:

Anti-Semitism in Poland After Auschwitz). The Jews are afraid of the

gentiles who in turn are afraid of the Jews, afraid of losing Jewish property

they have requisitioned. Post-war Lutsk is a wasteland. The somewhat

"literary" teller thinks of Ecclesiastes, of Bialik's

"BeIr haHarega" ('In the City of Slaughter'), of broken glass

reflecting the sun with total indifference. But the physical wasteland of Judenrein

Lutsk is less terrifying than the battered soul of Bashe, who was once a

charming young girl with long pigtails and played guitar and mandolin.

"Vitold Fomienko -- Mayn Reter" ('Witold

Fomienko -- My Rescuer'), an account of a young girl saved by a courageous

gentile, is corroborated in the records of YadVashem in Jerusalem. Together

with Shoshana Yakubovitsh's personal testimonial we cite the official

recognition of Witold Fiomenko's actions as recorded in YadVashem:

"Witold Fomienko hid scores of Jews in the

Lutsk region of the Ukraine, braving threats from Germans and hostile local

kinsmen." [cited from Yad VaShem's "Righteous Among Nations"

website].

There are over 30,000 recognized "Righteous

Gentiles" in the Yad Vashem memorial. They constitute a tiny minority of

the gentiles of Europe among whom millions of Jews were murdered, yet how much

they strengthen the human spirit by their example. In assessing their deeds we

must keep in mind the conditions under which they lived. Here is a

typical Nazi declaration against assisting Jews:

The Penalty for Helping a Jew in Occupied Poland:

The following proclamation was issued by Dr. Ludwig

Fischer, the German district governor of Warsaw, on November 10, 1941:

"Concerning the Death Penalty for Illegally Leaving Jewish Residential

Districts...Any Jew who illegally leaves the designated residential district

will be punished by death. Anyone who deliberately offers refuge to such Jews

or who aids them in any other manner (i.e., offering a night's lodging, food,

or by taking them into vehicles of any kind, etc.) will be subject to the same

punishment. Judgment will be rendered by a Special Court in Warsaw. I

forcefully draw the attention of the entire population of the Warsaw District

to this new decree, as henceforth it will be applied with the utmost

severity."

2)---------------------------------------------------

Date: 30 June 2006

From: Robert Goldenberg.

Subject: "Eygn blut"

יואל פּערעל

אייגן בלוט

איך בין געפֿאָרן קײן לויצק [לוצק]

אין יאָר 1945, װי מען פֿאָרט אױף קבֿר-אבֿות, מיט טיפֿן אומעט אין די אױגן, מיט

אַ גלײַכגילטיקן בליק אױף אַלץ און אױף אַלעמען, מיט אַ פֿאַרקלעמט האַרץ...

כ'האָב אַרומגעװאַנדערט איבער דער

הױפּטגאַס, די יאַגעלאָנסקע, און געזוכט אַ הײמיש פּנים, אַ באַקאַנטן. פֿאַר מײַן

פֿאַרנעפּלטן בליק איז נאָך אַלץ געשטאַנען דער אױפֿשריפֿט מיט די בלוטיקע װערטער

אױף דער מצבֿה – אַ געפֿאַרבטע, גראָבע בלעך אױף צװײ שטאַָלענע רעלסן אױפֿן

אָנגעשאָטענעם באַרג אין פּאָלאָנקע׃

„שמונה

עשׂר אלף איש עבריים יושבי עיר לוצק שנרצחו בידי רוצחי היטלר“ – אַכצן טױזנט!

צװישן זײ מײַן מאַמע, מײַנע פֿיר ברידער און דרײַ שװעסטער! צי איז שױן טאַקע קײנער

נישט פֿאַרבליבן?!

אַריבערגײענדיק די באַזיליאַנער

בריק, האָב איך באַמערקט נאָכן קלױסטער עטלעכע קריסטלעכע פֿאַרקױפֿערינס, װאָס

האָבן צעלײגט אױף די שטעלן זײערע סחורות. צװישן זײ – אײנע גאָר אַ באַקאַנטע׃ אַ שלאַנקע פֿרױ מיט אַ

מאַטאָװן פּנים, מיט טיפֿע שװאַרצע אױגן אָן שום אױסדרוק, מיט דינע ברעמען און

געדיכטע װיעס, שװאַרצע געדיכטע האָר, דורכגעװעבטע מיט אַ ברײטן פּאַס גרױע, כּמעט

װײַסע. האָב איך זיך געװאָלט דערמאָנען, װער איז זי? װוּ האָב איך זי געזען? זי

האָט באַמערקט װי איך קוק אױף איר. זי האָט זיך װי אַ ריס געטאָן צו מיר, נאָר זיך

דערמאָנט אין עפּעס און צוריקגעהאַלטן, אַראָפּלאָזנדיק שעמעװדיק די װיעס. נאָר

איך האָב זיך שױן דערמאָנט. בין איך צוגעגאַנגען צו איר און גאָר שטיל געטאָן א

שעפּטשע׃

- איר האָט מיך נישט דערקענט,

באַסקע?

- דערקענט, האָט זי נאָך שטילער

געענטפֿערט. נאָר באַמערקט, װי די אַרומיקע פֿאַרקױפֿערינס קוקן זיך נײַגעריק

איבער, האָט זי אױסגעלאָזט׃

- איר קאָנט אַרױפֿקומען צו אונדז

אין אָװנט... איך װױן... זי האָט אָנגעגעבן איר אַדרעס.

איך האָב שפּאַצירט װײַטער. דער

פּאַקראַװער קלױסטער שטײט גאַנץ, אַנטקעגנאיבער – די חורבֿות פֿון דער צענומענעם

הױז פֿון מײַנע עלטערן, װוּ איך האָב פֿאַרבראַכט מײַן קינדהײט און יוגנט. די שטוב

בײַם סאַמע שאָסײ, װוּ ס'האָבן געװױנט מײַנע שװעסטער פֿרײדע און רײזל, אױך מײַן

ברודער בנציון, שטײט נאָך, נאָר די אונטערשטע װאַנט, די בראַנדװאַנט, איז

אײַנגעפֿאַלן און די קיכן שטײען אָפֿן. (ס'האָט זיך אַרױסגעװיזן, אַז אין דער

נאַכט פֿון מײַן אָנקומען קײן לױצק איז די װאַנט אײַנגעפֿאַלן). אין די װױנונגען

הענגען מײַן ברודערס טעפּיכער, שטײט זײַן מעבל און נײ-מאַשין, אַפֿילו דער

ראַדיאָ. איך האָב דערזען די שרעקעװדיקע און דאָך עזותדיקע בליקן פֿון די

אוקראַינער, װאָס באַלעבאַטעװען

[בעלהבתּעװען] אין די װױנונגען, און זיך גיך

אָפּגעטראָגען.

אױך די קאַראַיִמישע שול, די

הילצערנע מיט די הױכע פֿענצטער, שטײט גאַנץ. כּמעט אַלע ייִדישע שטיבער אַרום ליגן

אין חורבֿות. די שמאָלע געסלעך זענען פֿאַרשיט מיט מיסט, מיט שטיקלעך גלאָז, װאָס

שפּיגלען אין זיך די זון-שטראַלן. אַרום איז פּוסט װי אין אַ מדבר.

אין דער גרױסער שול שטײען נאָר די

װענט, דער דאַך איז צענומען. אױך די שנײַדער-שול, די, „בוקר שול“ זענען רויִנירט.

אין מײַן געמיט ברומט דער ניגון

פֿון „איכה ישבֿה“. עס דערמאָנען זיך די שורות פֿון ביאַליקס „עיר ההריגה“: “די

זון האָט געלױכטן און דער שוחט האָט געשאָכטן...“

צוריקװעגס בין איך געגאַנגען מיטן

ברעג פֿון טײַך סטיר.(4) פּלוצעם איז מיר אַקעגן געקומען אַ יונגער מענטש, יאָשקע

ליבערמאַן, שמולקעס אַ ייִנגערער ברודער. מיר האָבן זיך צעקושט. ער האָט מיר

אַרײַנגעפֿירט צו זיך אין שטוב און באַקענט מיט זײַן פֿרױ – אַ בלאָנדע דײַטשקע,

אַ סך עלטער פֿון אים. און מיט זײער קלײן טעכטערל. דאָס װײַב איז אַ מאָל זײַן

ניאַנקע געװען, האָט געראַטעװעט זײַן לעבן. זי האָט מיך אױפֿגענומען װאַרעם,

גערעדט אַ נישקשהדיקן ייִדיש און דערצײלט אַ סך, אַ סך, װאָס האָט מיך אינטערעסירט

פֿון געטאָ-לעבן.

מײַן מאַמע, דערצײלט זי, האָט נישט

געװאָלט אַװעקגײן מיט די קינדער. איז געבליבן אין שטוב. דאָ, האָט זי געטענהט,

האָט זי אירע פֿערצן קינדער געבױרן, און דאָ װעט זי שטאַרבן. דעם טױט האָט זי

מקבל-פּנים געװען אין איר שװאַרץ סאַמעטן קלײד.

אַדורכגײענדיק דורך קרישטאַלקעס

מױער, װעלכן ער האָט מיט אַזױ פֿיל מי און מאַטערניש געבױט פֿאַר זײַן טאָכטער,

האָב איך זיך דערמאָנט אין דער פֿרױ, װאָס איך האָב דערקענט – באַסיע, „באַסקע די

משומדת“. איך געדענק זי נאָך פֿאַר אָט אַזאַ-אָ, אַ חנװדיק מײדעלע מיט לאַנגע

צעפּעלעך. פֿינף שװעסטער זענען זײ געװען. צװײ בלאָנדע און דרײַ שװאַרצע. מיט דער

עלצטער שװעסטער, חנה מיט לאַנגע בלאָנדע צעפּ און בלױע אױגן, האָב איך זיך

געחבֿרט. אַלע שװעסטער האָבן געשפּילט אױף מאַנדאָלינעס און

גיטאַרעס. בײַ זײ איז שטענדיק פֿול געװען די שטוב מיט יונגװאַרג, װי אין אַ

קלוב. אײן עלטערן ברודער האָבן זײ געהאַט – יחיאל – אַ שװאַרצער, מיט גראָבע

מענלעכע נעגער-שטיכן, מיט אַ האַרטן

באַסאָװן קול; ער האָט געזונגען אין שול בײַם חזן ראָזמאַרין.

באַסיע איז די ייִנגסטע געװען. אױף איר האָבן די ייִנגלעך

נאָך קײן אַכט נישט געלײגט – זי איז נאָך אַ קינד. אָבער אומבאַמערקט איז זי

אױסגעװאַקסן און געװאָרן אַ שײן, רײַף מײדל, אַ שילערין פֿונעם 7-טן קלאַס פֿון

„פּאָװשעכנע“ שול. מען פֿלעגט שעפּטשען,

אַז זי שפּאַצירט אַרום בײַ ליובאַרט-שלאָס מיט קריסטלעכע ייִנגלעך.

זי האָט זיך פֿאַרליבט אין אַ

פּױלישן בחור, אַ מוזיקער, װאָס שפּילט אױף אַ סאַקסאָפֿאָן. אירע עלטערן און

שװעסטער האָבן געמאַכט פּרוּװן זי צו באַװירקן, זי זאָל איבעררײַסן מיטן „שגץ“,

נישט פֿאַרשעמען די משפּחה. װײניק זענען פֿאַראַן ייִדישע פֿײַנע בחורים?...

ס'האָט אָבער נישט געהאָלפֿן. דער טאַטע פֿלעגט זי זידלען, האָט געפּרוּװט זי

שלאָגן אױך. די מאַמע איז אַרומגעגאַנגען װי אַ שאָטן און קײן אָרט זיך נישט

געפֿונען. די שטוב איז געװאָרן פֿאַר באַסקען װי אַ גיהנום. אײן מאָל איז זי נישט

געקומען אַהײם נעכטיקן. ס'האָט זיך אַרױסגעװיזן, אַז די מאָנאַשקעס פֿון מאָנאַסטיר

באַהאַלטן זי אױס. זײ גרײטן זי צום שמד. מען לערנט זי די קאַטױלישע תּפֿילות. זי

גײט מיט זײ אין קאָשטשיאָל און „מאָדליעט זיך“.

די עלטערע שװעסטער האָבן זיך

צוגעאײַלט חתונה האָבן. דער טאַטע מיט דער מאַמע האָבן זיך געזעצט שבֿעה נאָך דער

לעבעדיקער טאָכטער, װי נאָך אַ געשטאָרבענער. אין שטוב איז געװען שטרענג פֿאַרװערט

צו דערמאָנען איר נאָמען.

אַזױ איז אַװעק דער טאָג.

אָװנט, איך קלינג פֿאָרזיכטיק אָן.

הינטער דער טיר דערהערן זיך אײַליקע טריט. ס'עפֿנט אַ יונגערמאַן – אַ בלאָנדער

מיט העלע קעצישע אױגן. לױט דעם, װי ער באַגעגנט מיך, שטױס איך זיך אָן, אַז ער איז

באַסיעס מאַן. אַז זי האָט אים שױן דערצײלט װעגן אונדזער באַגעגעניש.

באַסיע האָט זיך אױפֿגעשטעלט.

אַװעקגעלײגט דאָס לעפֿעלע, מיט װעלכן זי האָט געהאָדעװעט איר טעכטערל, געמאַכט אַ

פּאָר טריט מיר אַנטקעגן און אױסגעשטרעקט די האַנט. זי האָט אַ ביסל לענגער

געהאַלטן איר האַנט אין מײַנער, װי זי װאָלט אױסדריקן איר פֿרײַנדלעכע באַציונג צו

מיר. איך האָב באַמערקט׃ זי איז גענוג בלאַס, די אױגן פֿול מיט טרױער, די

באַװעגונגען װי געמאָסטענע, פּאַמעלעכע.

- זײַט באַקאַנט מיט מײַן מאַן און

טעכטערל – האָט זי אַ זאָג געטאָן אױף פּױליש.

- זײער אָנגענעם – האָב איך

דערלאַנגט איר מאַן די האַנט.

- װי רופֿט מען דיך, מײדעלע? –

האָב איך זיך אַ װענד געטאָן צום העל-בלאָנדן קינד מיט בלױע אײגעלעך, מיט אַ

פֿאַרריסן פּױליש נעזל, װאָס איז שטאַרק געראָטן אין איר טאַטן.

- זאָסיענקאַ, זאָסיענקאַ

שטשערבינסקאַ – האָט זי געענטפֿערט מיט אַ האַרציקן קינדערשן שמײכל.

- װי הײסט דײַן טאַטע, זאָג מיר,

זאָסיענקע.

- מײַן טאַטע? װלאַדיסלאַװ. און די

מאַמע – בראָניסלאַװאַ שטשערבינסקאַ – האָט זי געענטפֿערט מיט שטאָלץ, זײַענדיק

צופֿרידן, װאָס זי האָט אױסגעהאַלטן דעם עקזאַמען.

- װלאַדיסלאַװ, זײַ אַזױ פֿיל גוט

און לײג דאָס קינד שלאָפֿן. – האָט באַסיע אַ בעט געטאָן דעם מאַן – שױן צײַט.

דער יונגערמאַן האָט גענומען דאָס

קינד אױף די הענט׃

- נו , זאָג אַלעמען

„דאָבראַנאָץ“.

- דאָבראַנאָץ, מאַמושו! – האָט

דער קינד זיך געזעגנט און אַ שטאַרקן קוש געטאָן דער מאַמען. דער מאַן איז שנעל

אַרױס מיטן קינד, האָט, װײַזט אױס, פֿאַרשטאַנען, אַז דאָס װײַב װיל בלײַבן מיט

מיר אַלײן.

- הײסט איר גאָר בראָניסלאַװאַ?...

דאָס איז מײַן פּױלישער נאָמען. אַזױ

האָט מיך אַ נאָמען געגעבן דער קשאָנדז, האָט זי גאָר פּשוט געענטפֿערט.

- ער איז אײַך געװיס צונוץ געקומען

דער נאָמען. איר זענט אַ דאַנק אים לעבן געבליבן.

- נישט דער נאָמען האָט מיך

געראַטעװעט. נישט דאָס װאָס כ'בין אַ

פּאָלקע, נאָר מײַן שװעסטער הענע.

- כ'פֿאַרשטײ נישט. װי קומט אײַער

שװעסטער אײַך צו ראַטעװען?- בין איך געװען פֿאַרװוּנדערט.

ס'איז געשען אַזױ – האָט זי

אָנגעהױבן דערצײלן – ס'איז אומגליקלעך, נאָר אַ פֿאַקט. אין דער צײַט פֿון דער

אָקופּאַציע האָב איך מיט מײַן מאַן און טעכטערל געװױנט, געװײנלעך, אױסער דער

געטאָ, װי קריסטן. „געלעבט“, אױב מען קאָן דאָס אָנרופֿן לעבן. מײַן מאַן פֿלעגט

פֿאַרװײַלן מיט זײַן שפּילן די שיכּורע דײַטשע אָפֿיצירן אין רעסטאָראַנען, האָט

פֿאַרדינט און צוגעשטעלט אַלץ װאָס מען דאַרף צו עסן. ס'איז מיר אָבער גאָרנישט

אָנגעגאַנגען. אַ גרױס בענקעניש נאָך מײַנע עלטערן, שװעסטער און ברידער, װאָס

מאַטערן זיך הינטער די װענט פֿון געטאָ,

האָט גענאָגט מײַן האַרץ װי אַ פּיאַװקע און נישט געלאָזט רוען. די גאַנצע

זעקס יאָר, װאָס איך בין געװען אַװעק פֿון די

מײַניקע, האָב איך כּמעט נאָך זײ נישט געבענקט. מײַן מאַן, מײַן קינד האָבן

מיר געמאַכט פֿאַרגעסן אין זײ. איך האָב געהאַט אַן אַנדערע סבֿיבֿה. כ'בין

געװאָרן אַ הײסע קאַטאָליטשקע. פֿון אָנהײב געצװוּנגענערהײט, דערנאָך מיטן גאַנצן

האַרצן. אין מײַנע תּפֿילות פֿלעג איך גוט בעטן אױך פֿאַר זײ, ער זאָל זײ מוחל

זײַן, װאָס זײ האָבן מיך פֿאַרטריבן. ס'האָבן זיך פֿון מיר דערװײַטערט אַלע מײַנע

פֿריערדיקע באַקאַנטע און קרובֿיִם. יעדער מענטש האָט זיך זײַן שטאָלץ. איך האָב

פֿאַרשטאַנען, אַז נישט נאָר איך בין געשטאָרבן פֿאַר זײ, נאָר אױך זײ – פֿאַר

מיר. נישטאָ שױן קײן װעג צוריק צום פֿאַרגאַנגענעם... אָבער איצט, װען זײ לײַדן

אַזױ שװער און אױסזיכטלאָז, האָב איך נאָך זײ געבענקט. פֿאַרלױרן מײַן רו. נישט

געקענט שלאָפֿן, נישט עסן. איר װעט מיר גלױבן, כ'האָב רחמנות געהאַט אױף אַלע

ייִדן, װאָס בעטן אױף זיך דעם טױט הינטער די װענט פֿון געטאָ... כ'פֿלעג אַלע טאָג

גײן אין קאָשטשאָל גאָט בעטן פֿאַר זײ, נאָר אױך מײַנע תּפֿילות האָבן מיר נישט

גרינגער געמאַכט. איך האָב געזען װי די מערדער פֿירן אַלע טאָג אַרױס

פֿול-געפּאַקטע מאַשינען מיט מענטשן – האַלבע סקעלעטן. מיט גלעזערנע אױגן, ערגעץ

װײַט צו פֿאַרניכטן. און מײַן האַרץ האָט שיער נישט געפּלאַצט פֿאַר װײטיק. אײן

מאָל, נאָך אַ גאַנצער נאַכט מאַטערן זיך אין איבערטראַכטן, האָב איך פֿאַרלאָזט

מײַן שטוב, מאַן און קינד און ... אַװעק אין געטאָ אַרײַן צו מײַנע עלטערן. אױב

אומקומען איז - מיט זײ צוזאַמען... די

עלטערן האָבן מיך אױפֿגענומען מיט אָפֿענע אָרעמס, װי כ'װאָלט געקומען פֿון ערגעץ,

פֿון אַ װײַט לאַנד. מיר האָבן זיך געקושט מיט טרערן אין די אױגן און געשװיגן...

נאָר די שװעסטער זענען געװען ברוגז, הלמאי כ'האָב פֿאַרלאָזט מאַן און קינד. אָבער

זײ האָבן אַזױפֿיל װאַרעמע געפֿילן מיר אַרױסגעװיזן, אַזױפֿיל זאָרג און

האַרציקײט, אַז ,ס 'איז מיר שװער געװען אַריבערצוטראָגן.

- ס'איז זײ שװער געװען צו

דערקענען, אַזױ מאָגער און אױסגעטריקנט זענען זײ געװען.

- אין אַ פּאָר טעג אַרום איז

געקומען אױך אונדזער רײ. מײַנע עלטערן, די שװעסטער, זײערע מענער און קינדער האָבן

אָנגעפֿולט די מאַשין.

- אין דער לעצטער מינוט האָט מײַן

שװעסטער הענע מיך אַ כאַפּ געטאָן און אַרױפֿגעשלעפּט אױפֿן בױדעם. דאָרטן האָבן

מיר זיך אױסבאַהאַלטן עטלעכע טעג. די אוקראַינישע פּאָליצײ האָט גענישטערט

אומעטום, ביז זײ האָבן אונדז געפֿונען און אַרײַנגעװאָרפֿן אין אַ פּוסטע װעלב

פֿון װײַסמאַנס מױער, נעבן קלױסטערל. מען האָט אַהין אַרײַנגעשלײַדערט נאָך אַ סך

מענטשן. דרײַ מעת לעת – אָן ברױט, אָן אַ טראָפּן

װאַסער, אָן פֿרישער לופֿט. מיר האָבן געבעטן אױף זיך דעם טױט און מקנא געװען די,

װאָס האָבן שױן זײערס איבערגעקומען. אױפֿן פֿערטן טאג האָט מען אונדז אַװעקגעפֿירט

צום אַלגעמײַנעם ברידער־קבֿר. מען האָט באַפֿױלן זיך אױסטאָן נאַקעט און

אַרױפֿלײגן זיך אין אַ רײ אױף די הרוגים, װעלכע זענען קױם, קױם פֿאַרשיט געװען.

איך בין געלעגן נעבן מײַן שװעסטער הענע אַ האַלב-טױטע, אַ גלײַכגילטיקע און

דורשטיקע נאָכן טױט, װאָס האָט צו לאַנג געלאָזט אױף זיך װאַרטן. פּלוצעם האָט זיך

מײַן הענע אַ הײב געטאָן און װי נישט מיט אירע כּוחות אַ געשרײ געטאָן׃

- װעמען װילט איר אומברענגען? דאָ

ליגט אַ פּאָלקע, אַ קאַטאָליטשקע. ס'איז געשען אַ טעות. פֿאַר װאָס קומט איר

אומצוקומען?

אױף איר געשרײ האָבן די מערדער

אָפּגעענטפֿערט מיט אַ שיכּור געלעכטער׃

- נו, אַרױס דו פּאָלקע. מיט דיר

װעלן מיר זיך באַזונדער אַ שפּיל טאָן...

- איך בין געבליבן און נישט

געװאָלט אַרױסגײן, נאָר הענע האָט מיך מיט די לעצטע כּוחות אַרױסגעשטופּט פֿון

גרוב.

- באַלד האָב איך, װי אין חלום,

דערהערט אַ הילכיקן זאַלפּ... מער האָב איך שױן גאָרנישט געזען און געהערט...

זײ האָבן מיך דערמינטערט, מען האָט

מיך דערלאַנגט אַ קלײדל אָנצוטאָן. איך האָב מעכאַניש געענטפֿערט אױף די פֿראַגן,

װער איז מײַן מאַן און װוּ ער װױנט. װי לאַנג ס'האָט געדױערט, געדענק איך נישט.

איך האָב פֿאַרלױרן דאָס געפֿיל פֿון אָרט און צײַט. װען מײַן מאַן מיטן קינד אױף

דער האַנט איז שפּעטער געקומען צו לױפֿן, האָב איך געקוקט אױף זײ, װי אױף פֿרעמדע, מיט פֿילער

רעזיגנאַציע און גלײַכגילטיקײט...

ס'זענען שױן אַריבער יאָרן פֿון דעמאָלט אָן,

איך לעב, עס און טרינק, נאָר... כ'האָב פֿאַרלױרן די לוסט צום לעבן, פֿאַרלױרן דעם

מענטשלעכן שמײכל... פֿאַרלױרן מײַן גלײבן...

[The Yiddish

texts were typed by Robert Goldenberg and unlike the digitized NYPL texts (see http://yizkor.nypl.org) are 1) searchable and

2) conform to the Standard Yiddish Orthography.]

2) (Cont'd) -----------------------------------------

Date: 30 June, 2006

From: Leonard Prager

Subject "Eygn blut" (English

translation)

I traveled to Lutsk in 1945 in a mood of one

visiting a parent's grave, deep sadness in my eyes, looking indifferently at

everything and everyone about me, my heart grieving …

I wandered along the main thoroughfare,

Crossing the

I continued my walk. The Prakov Cathedral still

stood. Opposite it were the ruins of my parent's demolished home where I had

spent my childhood and youth. The house near the main highway where my sisters

Freyde and Reyzl and my brother Bentsien lived still stood, though the lower

wall, the firewall, had fallen in leaving the kitchens exposed. (It seems that

during the night that I arrived in

Almost all the Jewish homes in the vicinity lay in

ruins. The little side streets were covered with trash and with pieces of glass

that reflected the sunlight. It was like a desert wasteland.

The wooden, tall-windowed Karaite Synagogue stood

intact. Of the Great Synagogue only the walls remained, the roof having caved

in. The Tailor's Synagogue and the "Morning" Synagogue were also

ruined.

In my mind there echoed the melody with which we

recite the Book of Ecclesiastes. Lines from Bialik's "In the City

of Slaughter" came to mind: "The sun shone … and the shokhet

slaughtered."

Turning back I walked along the bank of the

My mother, she explained, did not want to leave

with her children and remained at home. She insisted that this was where she

had given birth to her fourteen children and here she would die. She met death

in her black satin dress.

Going by the outer wall of the Krishtalke home,

built by a father for his daughter with so much effort, I thought of the woman

I had earlier recognized – Bashe, "Bashe the Apostle." I recalled how

she looked as a girl with long pigtails. They were five sisters – two blonde

and three black-haired. The oldest sister, Hannah, blue-eyed and with long

blonde pigtails, was a friend of mine. All the sisters played mandolins and

guitars. Their home was like a club, always full of young people. They had an

older brother, Yekhiel, dark-complexioned and with heavy, masculine negroid

facial features; he had a deep bass voice and sang in the synagogue with Cantor

Rosmarin.

Bashe was the youngest. Boys had not yet begun to

notice her – she was still a child. But unobserved by anyone she grew up and

developed into a mature young woman. She was a pupil in the seventh class of

the "Powszechnie" ('Public' ) School.

People used to whisper that she went around with

gentile boys by the

She fell in love with a Polish boy, a musician who

played the saxophone. Her parents and sisters tried to influence her to break

off with the "sheygets"

('gentile lad', used contemptuously) so as not to disgrace the family. "Weren't

there plenty of Jewish boys?" But nothing helped. Her father used to call

her names and even tried to beat her. Her mother walked about like a shadow and

found no rest anywhere. Home became a hell for Bashe. One night she did not

return home. It turned out that the sisters in the nunnery were teaching her

the Catholic prayers. She went to church with them and prayed with them.

Her older sisters hurried to marry. Mother and

father observed the traditional seven-day memorial period for the dead (shiva),

as though she were dead. It was forbidden to speak her name in the house.

This is how my day passed.

In the evening I cautiously rang the doorbell.

Someone stepped quickly on the other side of the door. A young blonde-haired

man with bright catlike eyes opened the door.

The manner in which he greeted me told me that he was Bashe's husband

and that she had told him of our meeting earlier in the day.

Bashe got up, put down the spoon with which she was

feeding her daughter, walked a few steps towards me and held out her hand. She

held my hand longer than mere greeting required, as though wishing to assure me

of her friendly feelings towards me. I saw how pale she looked, how tearful her

eyes were, how measured and slow her movements.

"Let me introduce my husband and daughter,"

she uttered in Polish.

-"Happy to meet you," I replied to her

husband, shaking his hand. Turning to the bright-blonde child with little blue

eyes and a turned-up Polish nose like her father's, whom she took after, I

asked, "What is your name?"

-"Zosyenka, Zosyenka Shtsherbinska," she

answered with a hearty child's smile.

-"Tell me, Zosyenka, what is your father's

name?"

-"My father? Vladislav.'

-"And your mother?"

"Bronislava Shtsherbinska," she answered

proudly, pleased with her successful performance."

-"Vladislav, be so kind as to put the child to

bed," Bashe asked of her husband. "It's time."

The young man lifted the child into his arms and

said to her: "Now say goodnight to everyone."

"Dobranoc!"

"Dobranoc, mother!" The child said

goodnight to her mother with a strong kiss. Father and daughter left the room

immediately. He evidently understood that his wife wished to be alone with me.

-"Is your name really Bronislava?"

-"That is my Polish name. It is the name the

priest gave me, " she answered simply.

-"That name surely proved useful. Thanks to it

you stayed alive."

-"It was not the name that saved me, nor my

being a Polska; it was my sister Hene who saved me."

-"I don't understand. How did your sister save

you?"

- "This is how it happened," she began.

"It is unbelievable but true. During the occupation my husband and I and

our child lived as Christians outside the ghetto. 'Lived' if one could call

that a life. My husband entertained the drunken German officers in restaurants

and earned enough to feed us. But I was dissatisfied. A great longing for my

parents, sisters and brother who were suffering behind the ghetto walls gnawed

at my heart like a leech and gave me no rest. During the six years in which I

was separated from my own family, I hardly missed them. Occupied with my

husband and child I forgot them. I lived in a different world. I became an

ardent Catholic, at the outset from pressures but later with my whole heart. In

my prayers I prayed too for my family, prayed they be forgiven for casting me

away, All my former acquaintances and relatives distanced themselves from me.

Everyone has their pride. I understood that not only was I dead for them, but

they were dead for me as well. There is no road back to the past, but now that

they were suffering so hopelessly I missed them. I could neither sleep nor

rest. I felt pity for all the Jews who begged to die behind the ghetto walls. I

used to go to church every day to pray for them, but not even my prayers

lightened my pain. I saw how the murderers transported wagonloads of people,

half-skeletons with glassy eyes, to murder them some place far away. My heart

almost burst with hurt.

Once, after a long night of anguish and of thinking

matters through, I left home, left husband and child, and went to join my

parents in the ghetto. If I was to die, then better to do so together with

them. My parents received me with open arms as though I had returned from a

distant land. With tears in our eyes we kissed and were silent. My sisters,

however, were angry with me for abandoning my husband and child. But they

showed such warm feelings toward me, so much concern and consideration that it

was hard for me to bear.

"It was hard to recognize them,they were so

thin and emaciated-looking."

"In a few days time, our turn came. My parents

and my sisters with their husbands and children filled a vehicle."

"In the last moment my sister Hene grabbed me

and pulled me up into an attic where we hid for several days. The Ukrainian

police rummaged everywhere and finally found us and threw us into an empty

store off Weissman's wall near the church. They squeezed many others into the

same space. We were there for three days – with no bread, without a drop of

water, with no fresh air. We prayed for death and envied those whose agony was

behind them. On the fourth day we were transported to a mass grave. We were

forced to undress and lie down on the rows of corpses of those who had preceded

us and not been covered. I lay near my sister Hene. I was half-dead,

indifferent to all, but thirsty for death which took too long to arrive.

Suddenly my sister Hene raised herself and with a force unlike her own, cried

out: "Whom do you want to kill? A Catholic Polish woman lies here. There

has been a mistake. Why does she deserve to die?"

The murderers answered her outburst with drunken

laughter: "Well then, out with the Polska, we'll attend to you

separately."

"I remained where I was. I did not want to

crawl out, but Hene, with her last remnant of energy, pushed me out of the

grave. Soon I heard a resounding volley. After that I saw and heard nothing.

They revived me and handed me a dress to put on. I answered questions

mechanically. Who was my husband and where did I live? How long all this took I

don't remember; I lost all sense of time and place. When my husband came

running with our child in his arms I looked at them with indifference and

resignation as though they were strangers.

"Since then years have gone by. I live, I eat

and drink. But I have lost all joy in life. I have lost the human smile…. I

have lost my belief…."

2) (Cont'd) -----------------------------------------

Date:

From: Robert Goldenberg

Subject "Vitold Fomienko -- Mayn

Reter"

שושנה

יאַקובאָװיטש / קאַנאַדאַ

װיטאלד

פֿאָמיענקאָ –מײַן רעטער(1)

איך

האָב שױן פֿיל מאָל גענומען די פּען אין האַנט, געװאָלט אָנשרײַבן װעגן דעם

באַליבטן און האַרציקן װיטיע פֿאָמיענקאָ.

די

נעמען פֿון די מענטשן, װעמען ער האָט אַזױ פֿיל געהאָלפֿן געדענק איך לײַדער נישט.

נאָר די פּנימער פֿון די ייִדן װעלכע ער האָט געראַטעװעט שטײען מיר נאָך הײַנט

פֿאַר די אױגן.

איך

האָב װ. פּאָמיענקאָ געזען דאָס ערשטע מאָל נאָך דעם װי מען האָט שױן אומגעבראַכט

אַלע אונדזערע פֿאַמיליעס אין לױצקער געטאָ. איך בין דעמאָלט דורך אַ צופֿאַל

געבליבן לעבן און אַנטלאָפֿן אין אַ דאָרף װאָס האָט געהײסן פּאַדהײַעץ.

דאָרטן

האָבן זיך געפֿונען פֿיל ייִדישע ייִנגלעך און מײדלעך, װאָס האָבן געאַרבעט אױף די

פֿעלדער. װ.פֿאָמיענקאָ פֿלעגט אָפֿט קומען צו זײ. ער האָט זײ געהאָלפֿן מיט

דערלײדיקן פֿאַר זײ דאָקומענטן און

מעדיקאַמענטן. צװישן אַנדערן האָט ער געבראַכט פֿאַר די ייִדישע מײדלעך

זױערשטאָף-װאַסער צום פֿאַרבן די האָר אױף בלאָנד, זײ זאָלן זיך קאָנען ראַטעװען,

אַנטלױפֿנדיק פֿון דאָרף.(2)

איך

בין דעמאָלט אַלט געװען 11 יאָר און האָב אױסגעזען װי אַ בלאָנד שיקסל, האָט מיר

װיטיעס מאַמע, לױט װיטיעס פֿאָרשלאָג,

גענומען צו זיך נישט געקוקט אױף דעם, װאָס ער האָט שױן געהאַלטן בײַ זיך אין הױז

פֿאַרבאַהאַלטן דרײַ ייִדן.

זײַענדיק

בײַ זײ, האָב איך געזען װי יעדן אָװנט פֿלעגן אַרײַנקומען ייִדן פֿון פֿאַרשידענעם

עלטער און דאָרט גענעכטיקט, גלײַך װי דאָס װאָלט געװען אַ האָטעל. מיטן אונטערשיד

װאָס אין האָטעל מוז מען באַצאָלן און דאָ האָט די משפּחה פֿאָמיענקאָ ריזיקירט צו

באַצאָלן און דאָי האָט די משפּחה פּאָמיענקאָ ריזיקירט צו באַצאָלן מיטן לעבן

פֿאַר איר גאַסטפֿרײַנדלעכקײט. ער האָט פֿאַר די צעשראָקענע און גערודפֿטע

געפֿונען באַהעלטענישן בײַ פֿאַרשידענע קריסטן. נישט אײן מאָל האָט װיטיע געצאָלט

פֿאַר זײ פֿון דער אײגענער קעשענע. די קריסטן האָט ער צוגעזאָגט גאָלדענע גליקן,

װי נאָר דער קריג װעט זיך ענדיקן, פֿאַרן אױסבאַהאַלטן די ייִדן. לײַדער האָט דער

קריג אָנגעהאַלטן מער װי מען האָט זיך געריכט און די שכנים פֿון די גוטע קריסטן

האָבן אָנגעהױבן צו באַמערקן, אַז עס װערן דורך זײ אױסבאַהאַלטן ייִדן, האָבן זײ

דאָס דערטראָגן צו דער פּאָליצײַ. גאָר אָפֿט האָט זיך דאָס פֿאַרענדיקט מיט

אױסגעבן דיִ ייִדן און מיט זײער דערמאָרדונג. דאַן האָבן זיך אָנגעהױבן נײַע צורות

פֿאַר װ. פּאָמיענקאָ און זײַן משפּחה. ער פֿלעגט אַרומגײן גאַנצע טעג און נעכט

און נאָר אַרױסקוקן דורך די שפּאַרונעס אױב מען קומט נישט צו אים אין שטוב זוכן

ייִדן. צום גליק האָט מען אים נישט געמסרט. עס האָבן אָבער אָנגעהױבן צו קומען

דערשראָקענע קריסטן, װעמען ס'איז געלונגען צו אַנטלױפֿן פֿון דער פּאָליצײַ און

געבעטן שוץ בײַ װיטיען, װײַל ער האָט זײ

דאָך געבעטן אױסבאַהאַלטן די ייִדן. און װיטיע האָט געמוזט זאָרגן װעגן די

באַהאַלטענע, זײ זאָלן קאָנען אַװעקפֿאָרן אין אַנדערע שטעט.

נישט

אײן מאָל איז געלונגען אַ ייִד אַרױסצודרײען זיך פֿון די דײַטשע לאַפּעס און

צוריקקומען צו װיטיען, װעלכער פֿלעגט מיט נײַע ענערגיע נעמען זיך זאָרגן פֿאַר

אײַנאָרדענען זײ אין זיכערע ערטער.

אױך

װיטיעס מוטער איז געװען זײער אַ פֿײַנע און גוטע פֿרױ. זײַן פֿאָטער איז געװען אַ

פֿײַנער און אײדעלער מענטש. איך האָב זײ זײער שטאַרק ליב געהאַט. איך אַלײן האָב

פֿון פּאָמיענקאָס פֿאַמיליע געהאַט פֿון שענסטן און פֿון בעסטן, סײַ צום עסן און

סײַ צום אָנטאָן. מײַן לעבן האָב איך זײ צו פֿאַרדאַנקען.

-------

1) 470

ספר לוצק, ע

2) Oxygen-water was used to dye hair blond.

2) (Cont'd)

-----------------------------------------

Date:

From: Leonard Prager

Subject "Witold

Fomienko – My Rescuer" (English

translation)

Shoshana Yakubovitsh /

"Witold Fomienko – My Rescuer"

I have taken pen in hand many times. I wanted to

write about beloved and good-hearted Vitye Fomienko. I'm sorry I can't remember

the names of all the people he helped so much, but the faces of the Jews whom

he saved are clear before my eyes.

I saw Witold (Vitye) Fomienko for the first time

after all our families in the Lutsk Ghetto had been killed. I stayed alive due

to chance and escaped to a small village by the name of Podhayets. Quite a few

Jewish boys and girls worked in the fields there and Vitye Fomienko visited

them often. He helped them get needed documents and medications. Among other

things, he brought oxygen-water for the Jewish girls so that they could dye

their hair blond, flee the village and save themselves.

I was then eleven years old and looked like a

little blond gentile child. At Vitye's request, his mother took me in – despite

the fact that he was already hiding three Jews in his home.

Living with them I noticed how persons of all ages

filed into their house in the evenings and slept there – as though it were a

hotel. With the exception that in a hotel you pay your bill, and here the

Fomienkos risked paying with their lives for their hospitality. Fomienko found

hiding places for terrified and hunted Jews with a number of Christians, not

once by paying from his own pocket. For hiding Jews he promised the world to

these Christians when the war ended. Unfortunately, the war went on longer than

people thought it would and neighbors of the good Christians began to see they

were shielding Jews and reported them to the police. Often this led to arrest

of the Jews and their subsequent execution. Then new troubles arose for Vitye

and his family. He was up day and night and kept watch through cracks in his

door fearful that his home would be searched for Jews. Luckily no one informed

on him. But frightened Christians who managed to escape from the police and

whom he had urged to shelter Jews began coming to him for help. And Vitye had

to find alternative hiding places in other locations for those he was already

hiding.

More than once a Jew managed to escape the clutches

of the Germans and returned to Vitye, who with renewed energy began to search

about for a new place to hide him.

Vitye's mother was also a fine, good woman; his

father was a fine and gentle person. I loved them very much. I myself received

from Fomienko's family the best of food and clothingt. I owe my life to

them.

3)--------------------------------------------

Date:

From: David Mazower

Subject: Portraits

of Yiddish Writers / Series 3: Irma Stern and Alva

Portraits of Yiddish Writers / Series 3: Irma Stern and Alva

By David Mazower

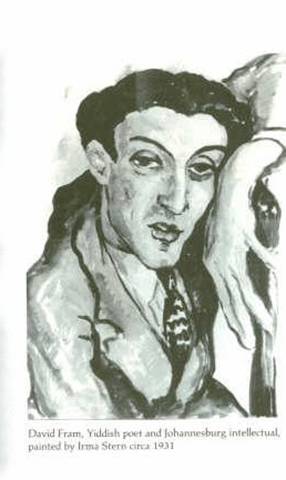

The

Jewish artists Irma Stern (1894 - 1966) and Alva (1901 - 73) grew up speaking

German and travelled widely in continental

Irma

Stern was born in 1894 in the

Stern’s

background and cultural milieu was that of the German-Jewish bourgeoisie, but

her exuberant and Expressionist-influenced paintings were inspired by

Stern’s

romantic portrait of Fram, painted around 1931, exemplifies her easygoing

lyricism. It catches the writer in a moment of contemplation, emphasising his

dark eyes, thick curly hair, and long fingers. It’s a romantic portrait of a

lyric poet and intellectual, and an informal picture of a friend.

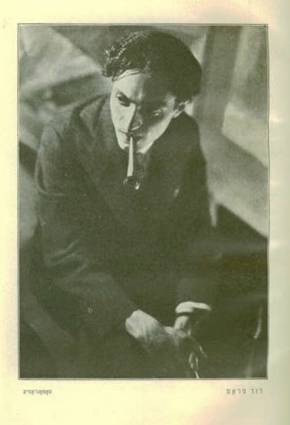

By

way of contrast to Stern’s portrait, a photograph of Fram, taken around the

same time and used as the frontispiece for the 1931 volume, presents us with an

emphatically modern image. The poet’s face is in deep shadow, the camera hovers

above and in front of the writer, and the background consists of abstract

interlocking shapes - a window, or perhaps canvases in an artists’ studio?

Interestingly, however, the photographer also accentuates the same features as

Stern: Fram’s hair, searching eyes, and hands, while adding another one - the

pipe dangling from his mouth.

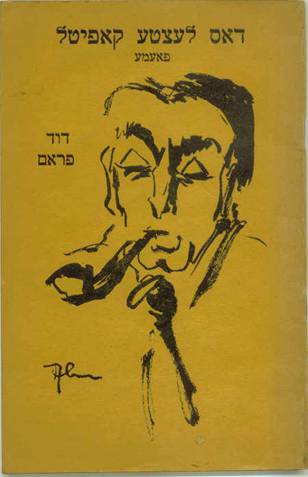

Fram,

like Stern, was a restless spirit who rarely stayed long in one place. He

stayed in London for extended periods in the

1930s and 40s, and it was there that his long poem Dos letste kapitl

(The Last Chapter) was published as a slim booklet in 1947, featuring a cover

portrait by an artist who called himself Alva.

This was the adopted name of Solomon Siegfried Allweiss.

Allweiss

was born in

Alva

was an occasional contributor of illustrations to Yiddish books published in

NOTES:

For

more about Dovid Fram, see the excellent tribute by Joseph Sherman in an

earlier edition of this journal (TMR, vol 08.001, January 2004)

Portrait of Dovid Fram by Irma Stern, c 1931

Photographic portrait of Dovid Fram, c 1931. (Photographer

unknown)

Portrait sketch of Dovid Fram by Alva, c 1947

Portrait sketch of Itsik Manger by Alva, c 1945

----------------------------------------

End

of The Mendele Review Vol. 10.006

Editor,

Leonard

Prager

Subscribers

to Mendele (see below) automatically receive The Mendele Review.

Send

"to subscribe" or change-of-status messages to: listproc@lists.yale.edu

a. For a temporary stop: set mendele mail postpone

b. To resume delivery: set mendele

mail ack

c. To subscribe: sub mendele

first_name last_name

d. To unsubscribe kholile: unsub

mendele

****Getting back issues****

The Mendele Review archives can be reached at: http://yiddish.haifa.ac.il/tmr/tmr.htm

Yiddish Theatre Forum archives can be reached at: http://yiddish.haifa.ac.il/tmr/ytf/ytf.htm

***