The Mendele Review: Yiddish Literature and Language

(A Companion to MENDELE)

-----------------------------------------------------------------

Contents

of Vol. 09.07 [Sequential No. 159]

Date:

1) This issue. (ed.)

2) The Goldfaden Micrograph (1897) (David Mazower)

3) A Note on Ignaz Bernstein (Lucas Bruyn)

4) Coming book reviews (ed.)

5) Books received (ed.)

http://yiddish.haifa.ac.il/tmr/tmr09/tmr09007.htm

1)-------------------------------------------------------------

Date:

From: Leonard Prager, ed.

Subject: This issue.

This

issue of TMR continues to probe the graphic arts in their relation to Yiddish

culture, in this instance via a unique art object, a micrograph, as it

connects to the founder of the Yiddish theater, Avrom Goldfadn [Abraham

Goldfaden]. This is followed by a short essay on the author of Juedische

Sprichwoerter und Redensarten, Ignaz Bernstein, which reminds Yiddish students

of a scholar who deserves to be remembered.

2)-------------------------------------------------------------

Date:

From: David Mazower (dmazower@yahoo.com)

Subject: The Goldfaden

Micrograph (1897): Portraiture and the Formation of Yiddish Literary Celebrity

The Goldfaden

Micrograph (1897): Portraiture and the

Formation of Yiddish Literary Celebrity

In a recent TMR article, I looked at Henryk

Berlewi’s satirical cartoon of the Vilna Troupe production of Ansky’s Dybbuk. In this issue I want to examine another

important but unknown graphic image from the world of Yiddish culture - a

micrographic portrait of Avrom Goldfadn (1840 - 1908) - placing it within the

context of the emergence of the Yiddish writer as celebrity and cultural icon.

The ideological battle for the hearts and minds

of the Jewish masses in the late 19th and early 20th

centuries was fought on many fronts. The

principal battleground was the war of words; Zionists, Bundists, orthodox

believers, Communists and secular Yiddishists all sought to win recruits

through debate, propaganda pamphlets, the popular press and at underground

meetings. But pictures and graphics also

played an important role. Commercial

postcards, satirical cartoons in the press, lapel badges and street posters all

helped to promote key figures and develop the idea of celebrity in an age -

almost impossible to imagine today - when few people knew what their heroes

actually looked like. (1)

The Zionist movement was quick to realise the

propaganda value of promoting images of Theodore Herzl and Max Nordau in the

1890s and 1900s. By contrast, there were

few key images of Yiddish writers in the same period - a time when the founding

fathers of Yiddish literature were in their prime. Only with the Yiddish language conference at

Czernowitz in 1908 did something resembling a classic image emerge - the widely

disseminated postcard featuring the writers Perets, Nomberg, Zhitlovski, Ash

and Reyzn. Here, belatedly, the Yiddish

literary world had found a match for the numerous conference photos already

produced by the Zionists.

By the 1910s and 20s, Jewish publishers and

printers in

The second generation of modern Yiddish writers

(Opatoshu, Manger, Ash and the rest) were more fortunate. Not only were they

featured regularly in the sepia photo supplements of the

The use of these elite art forms (and other

forms of portraiture such as the silhouette and minted medal) carried an

unspoken but important message: they contradicted the status of Yiddish

literature as a stepchild of the European literary family, insisting instead

that it deserved a place alongside other high-status mainstream cultures whose

leading personalities were routinely pictured by celebrated artists.

By contrast, the micrographic portrait

signifies something rather different. Hebrew micrography - the art of creating

pictures composed out of minute Hebrew letters - developed as a distinctive

form of religious art, invented by Jewish scribes in the early Middle Ages. For

centuries micrography was used almost exclusively in the religious sphere, for

Bible illustrations, amulets and ketuba decoration. From the late nineteenth century, portraits

of famous rabbis, Biblical sites and scenes from the scriptures were reproduced

as lithographic prints and sold as commercial artefacts. (2)

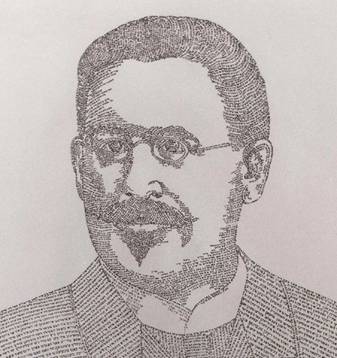

Portrait of Avrom

Goldfadn

(click to enlarge; when done – click the back

arrow)

Around the 1890s the Hebrew micrograph was

adopted by the Zionist movement.

Theodore Herzl, Max Nordau, Rabbi Moses Gaster and the writer Bialik

were all portrayed in micrographic form, as an essentially devotional art

gradually moved into the secular sphere. There was even a micrographic portrait

of Kaiser Wilhelm 2nd, composed from his biography in Hebrew translation,

and issued in honour of his visit to

All the more surprising, then, that (to the

best of my knowledge) there is not a single micrographic portrait of

Sholem-Aleykhem and Mendele and only a later and small-scale picture of

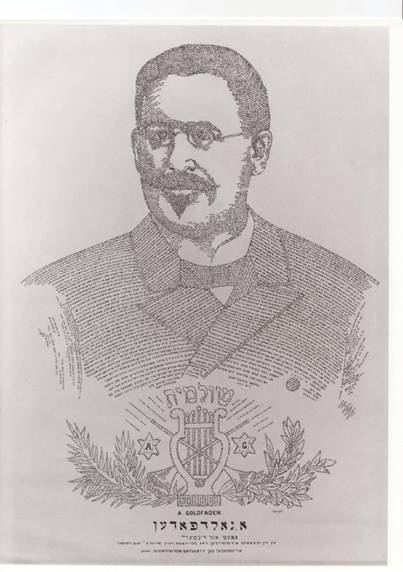

Perets.(5). There is, however, a superb 68 x 49 cm. micrographic portrait of

the Yiddish poet, playwright and operetta composer Avrom Goldfadn. Printed in

A. Goldfaden / poet und

dikhter / in zayn geshtalt iz geshriben dos berihmte verk “shulamis” 37.404

verter / aroysgegeben fun l.rotblat un goldshmit.

(A. Goldfaden / poet and writer / in his

portrait is written the famous work “Shulamis” 37.404 words / published by L

Rotblat and Goldshmit.

By 1897 Goldfadn was at the height of his

celebrity. His plays were being performed in Yiddish theatres across

By the time of his death in

The exact circumstances of the micrograph’s

creation are unclear. In 1897 Goldfadn

went to

Goldfadn micrograph

(click to enlarge; when done – click on the back

arrow)

What is not in doubt is that Goldfadn had many

admirers in

Observers of the early Yiddish stage frequently

commented on the fervour with which the audience joined in the spectacle. For

the impoverished playgoer, the early Yiddish drama halls and clubs inspired the

same devotion as synagogues and the playwrights were viewed with the same

admiration and awe as the most famous rabbis.

We should not be surprised, therefore, that a form of portraiture associated

with distinguished rabbis and political leaders has been chosen to venerate a

figure like Avrom Goldfadn. The Goldfadn

micrograph of 1897 both reinforces and pays tribute to the early Yiddish

writer’s celebrity status, and also stands as a testament to his immense

popularity.

Notes

1. For a

wide-ranging discussion of these issues, see Michael Berkowitz, The Jewish

Self-Image,

2. Leila

Avrin pioneered research into this neglected subject. See the book co-written

by her and Colette Sirat: La lettre hebraique et sa signification /

Micrography as Art,

3. Avrin

and Sirat’s book contains reproductions and provenance details of the

micrographic portraits of Rabbi Isaac Elhanan Spector, Theodore Herzl, the

Chief Rabbi of Vienna Zvi Peretz Chajas, and Kaiser Wilhelm II. For a reproduction of the Gaster micrograph,

see Leila Avrin’s 1981 exhibition catalogue Hebrew Micrography, One Thousand

Years of Art in Script, published by the

4. There

are a small number of micrographic or quasi-micrographic portraits in other

languages. A folio-sized memorial

portrait of Martin Luther, done in the year of his death, 1546, and composed of

minute Gothic-style German letters, was sold at Sotheby’s approximately twenty

years ago. Around 1905, a

5. The

micrographic portraits of Perets (drawn by Yoysef Troyber, and consisting of

the words to the author’s poem ‘Monish’) and Avrom Reyzn (drawn by N

Kopelovitsh in Vilna in 1938, using the words from several of Reyzn’s poems)

are reproduced in Melech Grafstein’s survey, Sholem Aleichem Panorama,

London, Ontario, 1948, pp. 200 - 201. On page 192 of the same book, there is a

reproduction of a micrographic portrait of Bialik, published in Tel Aviv. I am aware of two further micrograph

portraits of Yiddish writers: Yoysef Opatoshu (also drawn by Yoysef Troyber,

and reproduced in Ber Kutsher’s book Geven amol varshe / zikhroynes,

Paris, 1955, p237); and Nokhem-Meyer Shaykevitsh (Shomer), unseen but described

in his daughter’s memoir as “a picture of my father….made up of minute script

in which the story of his life was told” (see Miriam Shomer Zunser: Yesterday

/ A Memoir of a Russian Jewish Family, Harper and Row, New York, 1978,

p182); have any copies of this micrograph survived?

6. The

Goldfadn micrograph is now in a private collection; I am grateful to the owner

for allowing me to reproduce it for this article.

7. An

example was exhibited a few years ago in the

8. For

more on the actor, see Leonard Prager, Yiddish Culture in Britain, Frankfurt

am Main: Peter Lang, 1990, p. 287.

9. See

"The Ghetto Kipling - Father of the Yiddish Stage, Abraham

Goldfaden," The Jewish World,

3)-----------------------------------------------------------

Date:

From: Lucas Bruyn

Subject: A Note on Ignaz

Bernstein

Ignaz Bernstein (1836-1909)

Ignaz

Bernstein is known as the author of Juedische Sprichwoerter und Redensarten,

a collection of 3987 Yiddish "shprikhverter un redensartn" (proverbs

and expressions). A short biography by Herman Rosenthal written at the time

Bernstein was still alive can be found in the on-line Jewish Encyclopedia.

The first version of the "Shprikhverter" was published in 1888-1889

in Der Hoyz Fraynd. On the latter, Leonard Prager writes: "Two

anonymous collections of Yiddish proverbs appeared here. They were acknowledged

as Ignats Bernshteyn's and in an expanded and revised form later published as a

book (1908). The separate offprint of the 2056 proverbs in the Hoyz Fraynd version is thus the first edition." (Yiddish

Literary and Linguistic Periodicals, 1982, p. 79) Bernstein confirms this

in his 1907 "Vorwort"

(Introduction) to the 1908 work:

"In den Jahren 1888 und 1889 erschienen in

dem von M. Spektor herausgegebenen Jahrbuch Der Hausfreund zwei anonyme

Sammlungen juedisher Sprichwoerter, die aus meinem handschriftlichen Material

stammten und die gleichzeitig als Separatausgabe in einen kleinen Anzahl von

Exemplaren in zwei Heften abgedruckt wurden. Jeder dieser Sammlungen war fuer

zich nach dem Anfangsbuchstaben des ersten Wortes alphabetisch geordnet und

beide enthielten zusammen 2056 Sprichwoerter mit fortlaufender

Numerierung."

[Two

anonymous collections of Yiddish proverbs from my materials in manuscript came

out in 1888-1889 in the yearbook published by M. Spektor "The House

Friend". They were simultaneously published in a separate limited

two-volume edition. In these two volumes

the proverbs were placed in alphabetical order, according to their first words;

in total 2056 progressively numbered proverbs.]

Even earlier some of Bernstein's materials had

been incorporated in Karl Friedrich Wilhelm Wander's monumental Deutsches

Sprichwoerter-Lexikon ; ein Hausschatz fuer das deutsche Volk (1867-1880).

The 1908 editon is the "tsveyte,

shtark fermehrte un ferbeserte oyflage" and contains the "shprikhverter"

in Hebrew script as well as a transcription. Some of the entries are

accompanied by a short explanation in Yiddish and German. There is an index and

an 84-page glossary of words and expressions appearing in the proverbs that

derive from foreign languages (Hebrew/Aramaic, Slavic and Romance) or that are

less common. This glossary, with the Yiddish in transcription (Hebrew added if

appropriate) and translation in German, contains about 1600 words, including

several not found in Harkavi or Weinreich. It also gives etymologies of words,

not found in other dictionaries.

At

the time Bernstein wrote his work neither the YIVO standardized spelling of

Yiddish nor the YIVO romanization had yet been developed. Bernstein had to

devise a spelling and a transcription himself. As models for his orthography he

took contemporary literature and magazines. Thus he decided against using

doubled consonants. He based his transcription on the "Podolisch-wolhynische

Mundart". The resulting orthography looks much like the one used by

Harkavi (e.g. "nehmen" instead of "nemen"); his

transcription looks strange to the modern reader used to the YIVO/Weinrech

method. Although the Shprikhverter have been around for about a century,

it does not seem to be very popular with Yiddishists – but I may be wrong here.

An undated wholly Yiddish edition of the 1908 work – without the Erotica

-- duplicating right-side pages only that was published by the Brider Kaminski

Farlag in New York points to some demand for the book. This edition has exactly

the number of pages for main section (294) and Index (296-329) as has the

deluxe 1908 edition, but omits the Latin-letter "Glossar." A note on

the reverse side of the title page of this economical edition reads: "dos

bukh iz gedrukt loyt dem foto-ofset protses, derfar dershaynt es mit der alter

ortografye" (The book is printed by the offset process, therefore it has

the old orthography." This spelling

awareness suggests the 1950s – Stutshkov's Oytser was published in 1950. In the Mendele

list, Bernstein's Erotica was mentioned several times, but the main work

of proverbs was never quoted as a source. Availability cannot be the entire

problem, since the book can be bought at antiquarian bookstores – though at

very high prices today.

Here

is some further bibliographic information about Bernstein's work: The second

edition of the "Yudishe shprikhverter" came out in 1908, in

[This

collection of Yiddish proverbs with an erotic or colored content is published

following the Big Book of Yiddish Proverbs of Ignats Bernstein that came out in

1908 in Frankfurt am Mainz. Note: This book was published as the second volume

of the Library for Jewish Biblophiles, 300 numbered copies in total.]

About

a hundred years after the first appearance of the Shprikhverter a new

edition came out in the United States of America: Yidishe shprikhverter

[gezamlt un aroysgegebn fun] Ignats Bernshteyn ; tsugegreyt tsum druk, Y.

Birnboym. Nyu-York (

It

had been preceded by an American reprint of the Erotica et turpia in the

seventies (exact date and publisher unknown) and by a different edition of the Erotica

and Rustica with English translations: Yiddish sayings mama never taught

you. [compiled by Ignaz Bernstein ; translated] by Weltman &

Zuckerman.[

Bernstein

was neither the first nor the last paremiologist with an interest in Yiddish

sayings (paremiology, the study of proverbs). CATNYP lists 47 studies of

Yiddish proverbs and there are no doubt many more. Some of the early ones we

may mention are: Tendlau, Abraham Moses, 1802-1878. Sprichwoerter und Redensarten

deutsch-juedischer Vorzeit; als Beitrag zur Volks-, Sprach- und

Sprichwoerter-Kunde, aufgezeichnet aus dem Munde des Volkes und nach Wort und

Sinn

erlaeutert von Abraham Tendlau. Frankfurt a. M., H. Keller, 1860.

Wahl, Moritz Callmann, 1829-1887 Das Sprichwort

der hebraeisch-aramischen Literatur, mit besonderer Beruecksichtigung des

Sprichwortes der neueren Umgangssprachen. Ein Beitrag zur vergleichenden

Parmiologie ... Buch 1. Zur Entwicklungstheorie des sprichwoertlichen

Materials.

Bernstein

wrote only one other book, a catalogue of his collection of about 8400 books on

proverbs, folk-lore ethnography etc.: Bernstein, Ignatz. Catalogue des livres

paremiologiques, composant la bibliothque de Ignace Bernstein. Varsovie, de

L'imprimerie W. Drugulin Leipsick, 1900. Added t.p. in Polish: Katalog dziel

trsci przyslowiowej. A reprint of this work was issued by Olms (

A

modern study, relying on Bernstein is Magdalena Sitarz, Yiddish and Polish proverbs : contrastive

analysis against cultural background,

Available

reprints:

BERNSTEIN,

IGNAZ. Catalogue des livres parémiologiques composant la

bibliothèque de Ignace Bernstein / Catalogue of Ignace Bernstein's

Collection of Proverb Literature / Katalog von Ignaz Bernsteins Bibliothek der

Sprichwörterliteratur / Katalog dziel tresci przyslowiowej skladajacych

bibljoteke Ignacego Bernsteina [ISBN: 3-487-11437-2] 268,00 Eur

BERNSTEIN, IGNAZ. Jüdische Sprichwörter

und Redensarten [ISBN: 3-487-02298-2] 99,80 Eur .

Georg Olms Verlag AG Weidmannsche

Verlagsbuchhandlung GmbH Hagentorwall 7, D-31134 Hildesheim Tel: ++49 (0) 5121

/ 150 10 Fax: ++49 (0) 5121 / 150 150. E-Mail: info@olms.de

4)---------------------------------------------

Date:

From: ed.

Subject: Coming book reviews

The

next issue will be devoted solely to Menke, edited by Dovid Katz and

Harry Smith. Dovid Katz's Lithuanian Jewish Culture (Vilna: Baltos

Lankos, 2004, 398 pp), will yet be reviewed in TMR, as will be Nancy

Sinkoff's Out of the Shtetl (

5)---------------------------------------------

Date:

From: ed.

Subject: Books received

Der Nister [HaNistar], Maasiyot

beKharuzim, tirgem meYidish veHosif mavo Shalom Luria.

[Sifriat Khulyot 2]. The

editor of Khulyot, Shalom Luria, gives us lively Hebrew renderings of

eleven of the careful artist Der Nister's tales in verse written for children

but adored by adults.

The translator's introduction

is an expanded version of an essay that first appeared in Khulyot 2

(1994), 151-168. The front

cover by David Luria shows us a shretele (little elf) in a tall hat.

-----------------------------------------------

End of The Mendele Review Vol.09.07

Editor, Leonard Prager

Subscribers to Mendele (see below) automatically

receive The Mendele Review and the Yiddish Theatre Forum.

Send

"to subscribe" or change-of-status messages to: listproc@lists.yale.edu

For

a temporary stop: set mendele mail postpone

To

resume delivery: set mendele mail ack

To

subscribe: sub mendele first_name last_name

To

unsubscribe kholile: unsub mendele

****Getting back issues****

The Mendele Review archives can be reached at: http://yiddish.haifa.ac.il/tmr/tmr.htm

Yiddish Theatre Forum archives can be reached at: http://yiddish.haifa.ac.il/tmr/ytf/ytf.htm