The Mendele Review: Yiddish Literature and Language

(A Companion to MENDELE)

---------------------------------------------------------

Contents of Vol. 12.014 [Sequential No. 205]

Date: 25 July 2008

1)

This issue of The Mendele Review

2) "The Jerusalem Conference: A Century Of Yiddish

1908-2008" (Yechiel Szeintuch)

3) A Note on Avrom Karpinovitsh (ed.)

4) "Zikhroynes fun a farshnitener teater heym" [Part One – Yiddish Text] (Avrom

Karpinovitsh)

5) "Memoirs of a Lost Theatre Home" [Part One –

English Translation by Shimen Yofe]

[Shimon Joffe]

6) First Afro-American to Earn Ph.D. in Yiddish Studies

(Jennifer Hambrick)

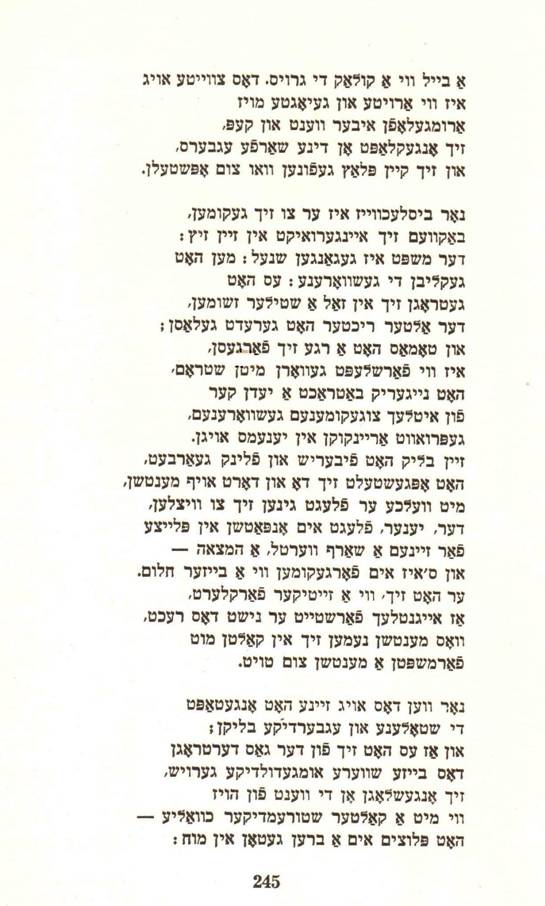

7) "Gerekhtikeyt"

('Justice') from Y.-Y. Shvarts' Epic Kentuki (Robert Goldenberg)

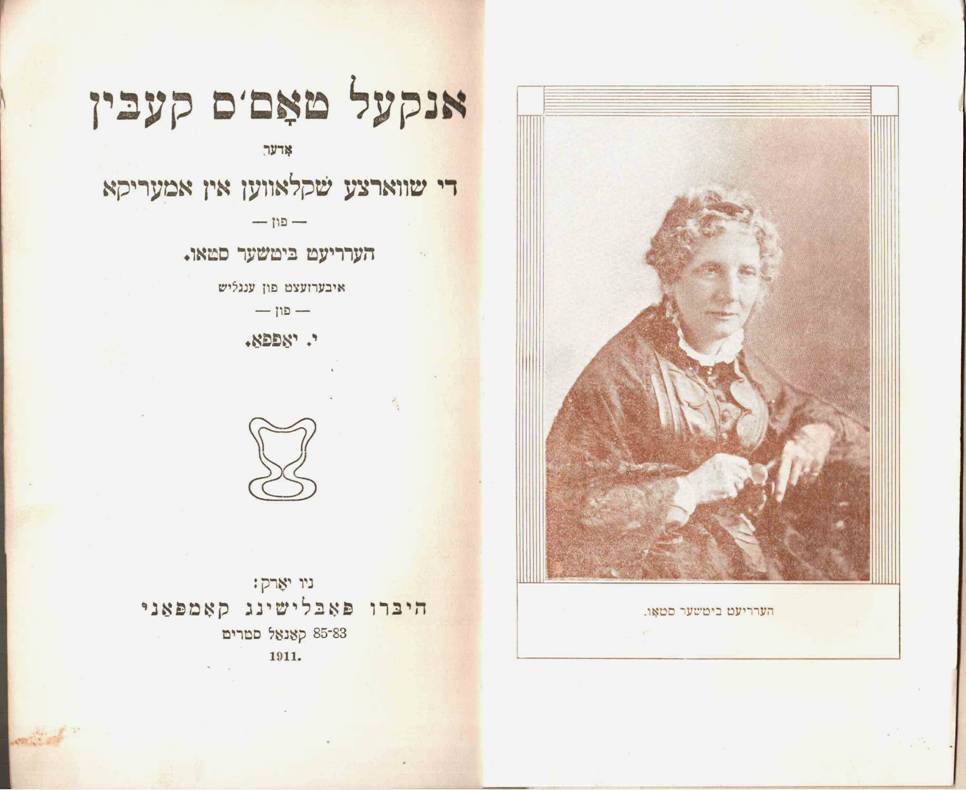

8) Yiddish versions of Uncle Tom's Cabin (Robert Goldenberg)

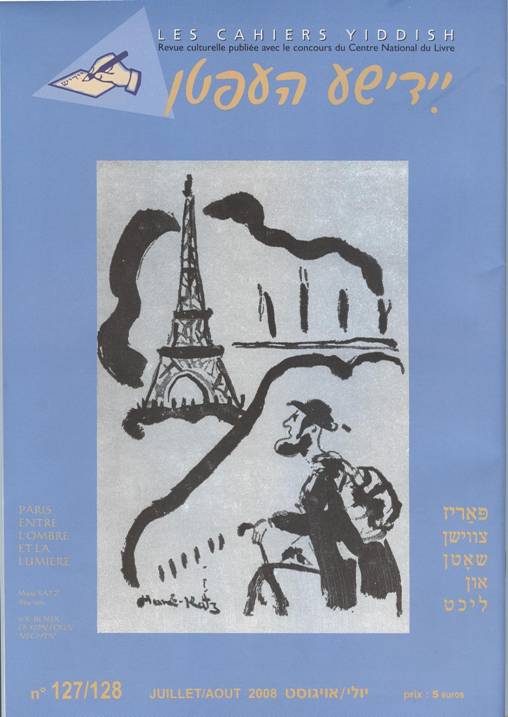

9) Periodicals Received: Yidishe

heftn no. 127/8 [July/August 2008]. Issue theme:

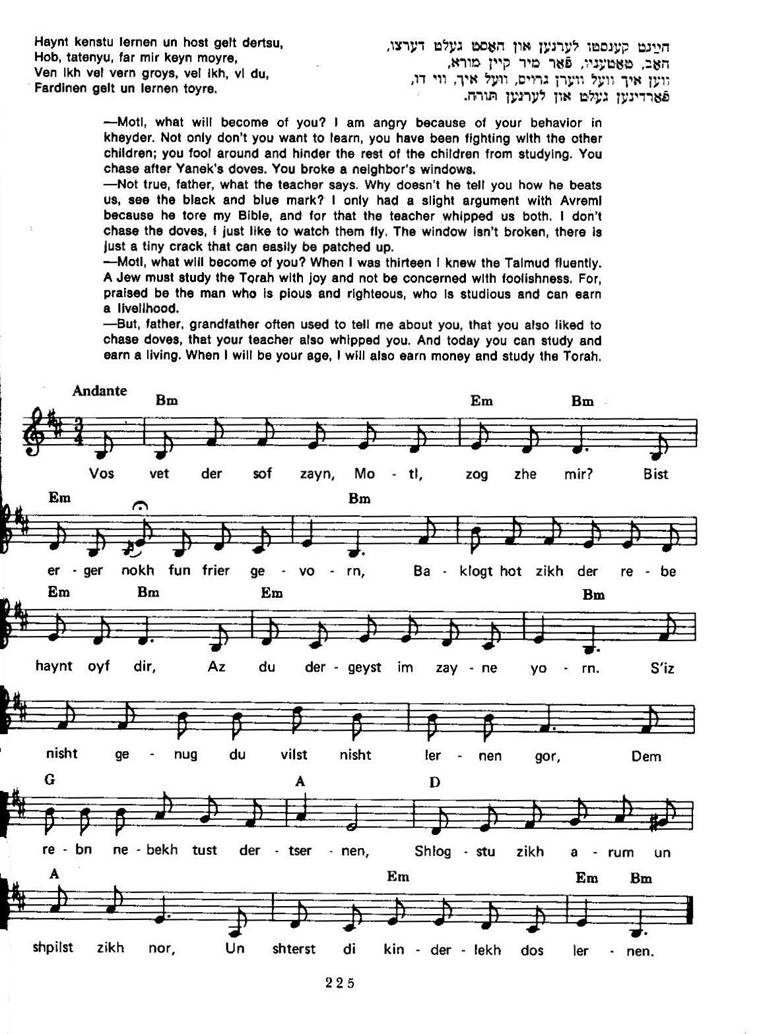

10) Cover of songbook, Mir trogn

a gezang [includes Gebirtig's

"Motele"] (Eleanor Mlotek)

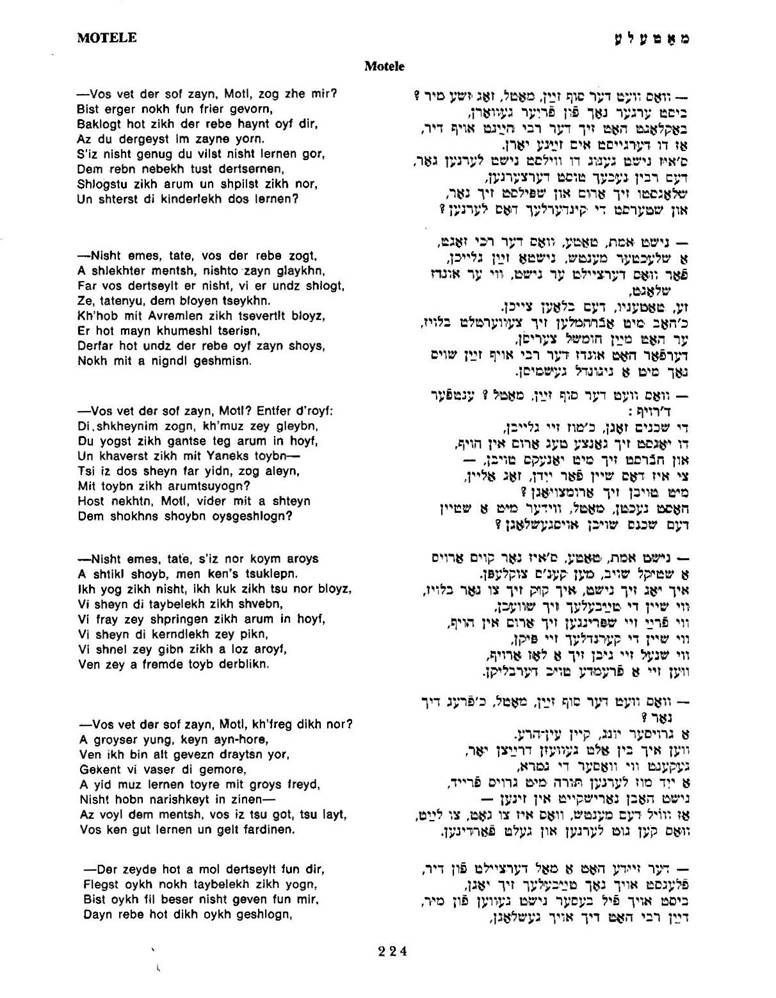

11) "Motele" lyrics

and score (Eleanor

Mlotek)

12) "Motele" sung by Menakhem Bernshteyn

13) Portrait and biographical sketch of Menakhem

Bernshteyn [Menachem

Bernstein], Haifa-based folksinger and reciter.

1) ---------------------------------------------------

Date: 25 July 2008

From: ed.

Subject: This

issue of TMR

This somewhat

crowded issue of TMR welcomes the first Afro-American Yiddish scholar to

our Yiddish studies community, reproduces "Gerekhtikeyt"

('Justice'), a moving section of Y.-Y. Shvarts' epic Kentuki (1948), and dwells briefly on Yiddish

versions of Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin. A newcomer to

Yiddish translation gives us his rendition of an Avrom

Karpinovitsh text, and we conclude with a section on

the Gebirtig song "Motele",

sung by another newcomer to the TMR.

2) ---------------------------------------------------

Date:

25 July 2008

From: Yechiel Szeintuch

Subject: "The

One reason for

planning the conference was to address three major issues about Yiddish and

Yiddish culture in the last one hundred years:

1. Yiddish cultural history in the last century.

2. Existing active Yiddish culture in the Jewish world.

3. What to reinforce and what future projects that serve Jewish studies to plan

for.

The organizing

committee is interested in receiving feedback concerning these three issues.

Replies will be distributed to conference participants by the Dov Sadan Project at the

Please write

to dovsadaninst@mscc.huji.ac.il

The Organizing

Committee

3) ---------------------------------------------------

Date:

25 July 2008

From: ed.

Subject: A Note on Avrom

Karpinovitsh

Avrom Karpinovitsh

was born in 1913 in Vilna, the city which became his lifelong subject. During World War Two he lived in the

Reference: Nayer leksikon

fun der yidisher literature,

Vol. 8, cols. 147-8.

4) ---------------------------------------------------

Date:

25 July 2008

From: Avrom Karpinovitsh

Subject: "Zikhroynes

fun a farshnitener teater heym" [Part One – Yiddish Text]

"Zikhroynes fun a farshnitener teater heym" [Part One –

Yiddish Text]

5) ---------------------------------------------------

Date:

25 July 2008

From: Shimen Yofe [Shimon Joffe]

Subject: "Memoirs of a Lost Theatre

Home" [Part One – English Translation by Shimen Yofe]

"Memories of a Lost Theater Home" (Part One)

When theater-goers were scarce and income low, and the task of running

the household became unbearable, my mother would burst out with "I wish

this business would go to the devil." My father at such moments would look

at her with his dark shining eyes, full of accusation, and groan. "Rachel,

Rachel, how can you say such a thing?" My mother, out of regard for him,

would not reply. She would give a wave

of her hand and go off to the kitchen to prepare a modest meal. Had she held my

father's look for just a moment, she would have seen herself reflected in her

own curse. The theater burned in my father's eyes – burned and was not

consumed.

*

My father's father was a rabbi in Slobodke, a

poor section of

There was another apprentice working in the printing shop, a relative

of the partner Shriftzetser. The two boys became

attached to one another. Both of them, while bending over a layout of a page of

the Talmud were carried away by thoughts of other worlds: bright and colorful,

the opposite of the leaden gray of the printing works. My father's friend later

became well known as the actor Shlomo Shriftzetser, a masterful portrayer of Sholem

Aleichem characters on the stage.

In later years my father and Shlomo Shriftzetser continued to recount youthful stories

about each other. Again and again, my

father would tell how Shriftzetser dressed up as a

devil and frightened the workers out of their wits. Shriftzetser

related how on one occasion my father

was found hanging upside down in the attic and was quickly taken down -- he

wanted to know how long he could hang head down since he was preparing himself to become a circus acrobat.

Shlomo Shriftzetser's

path to the theater was swift. He was an actor body and soul. My father, on the

other hand, never became an actor. Though he himself lived in constant inner

turmoil, he could not give expression to this condition. The quiet background

of a rabbi's home constrained him. He tried his powers on the stage just once,

and that was by accident. The actor Ayzik Samberg,

one of the most prominent players on the Yiddish stage in the period between

the two World Wars, was taken ill. He had the role of the Messenger in Anski's Der Dybbuk, a very successful play in the thirties. In my father's theater, it played for a whole

season to full houses, even pleasing my mother. And now, a misfortune occurred

-- Ayzek Samburg took ill

and there was the possibility that a few performances might have to be

canceled. My father dug in his heels. Performances that draw crowds cannot be

canceled, he declared. And he also didn't want to lose the income, so badly

needed to run the business. My father convinced the actors' committee headed by

Avrom Moreski, who played

the Miropil Tsadek

('saintly man') in this play, that he could substitute for Aizik

Samberg until the latter recovered "A beard I have," he said -- my

father started his beard when a young man -- " so I'll put on a kapote ('kaftan') and say a few words."

He made his first and last debut in the role of the Messenger at a

Saturday matinee, walking onto the stage dressed in his own beard and a kapote and quietly whispered the

well known words "The bridegroom will arrive in time." Someone in the

audience didn't hear him clearly and shouted out, "Karpinovitch,

talk louder." My father promptly answered:

"I am not an actor, I am only replacing Samberg, so I don't have

to talk louder." With this appearance my father bid farewell to the stage

for good. He no longer wanted to replace anyone, even at the cost of closing

the booking office.

My father came to the theater indirectly. While his friend Shlomo Shriftzetser toured

*

World War One broke out. Hunger reigned in my mother's cast iron

cooking pot. My father spent whole days running about looking for bread to feed

his family. An honored ancestral name came to his aid -- the rabbi of Shnipishok,

my grandfather's friend, sent my father to talk to the city commandant about

founding a free kitchen to feed the poor in the suburb of

My father convinced the general to release food for the free kitchen.

In this he was assisted by a soldier who worked in the staff office. The

soldier's name was Arnold Zweig, later to become famous as the author of The Case of

Sergeant Grischa, a work based on a true case that came to

the author's attention while serving in Vilna. Arnold Zweig, in spite of his

being assimilated and far removed from Jewishness,

took much to heart father's desire to save Jews from hunger. I remember, as if

through a thick fog, the

The theater, it would seem, was father's fate written in the heavens.

Among the cooking pots in the kitchen, a bit of theater was played out by a

dark pretty little girl, who, like a kitten, would rub herself against father's legs. Her mother worked in the

kitchen peeling potatoes. The little girl later was celebrated on placards under

the name Khayele Kushner. She acted in the Yiddish

theater in

____________________________

Avrom Karpinovitsh

[Abraham Karpinowitz], "Zikhroynes

fun a farshnitener teater heym," in Vilna, mayn Vilna, Tel-Aviv: I.L. Peretz Publishing House, 1993, pp. 85-100. [Note: this text

has been arbitrarily divided into three parts for the convenience of the

reader.]

6) ---------------------------------------------------

Date:

25 July 2008

From: Jennifer Hambrick, The New Standard

Subject: First Afro-American to Earn

Ph.D. in Yiddish Studies

The url below points to a popular article about a fledgling

African-American Yiddish scholar whom TMR is pleased to welcome to the Yiddish studies

community. Following the article are comments of a number of readers concerned

that Yiddish in roman letters be written according to the well-established Yivo rules – a sentiment that TMR vigorously

encourages.

http://www.tnscolumbus.com/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=2932

7) ---------------------------------------------------

Date:

25 July 2008

From: Robert Goldenberg

Subject: "Gerekhtikeyt"

('Justice') from Y.-Y. Shvarts' Epic Kentuki

"Gerekhtikeyt" ('Justice', 1922)

8)

---------------------------------------------------

Date:

25 July 2008

From: Robert Goldenberg

Subject: Yiddish versions of Uncle

Tom's Cabin

In his

overview article "America" in the groundbreaking Encyclopaedia

of Jews in Eastern Europe (Yale/Yivo,

2008), Eli Lederhendler writes: "The prolific Ayzik-Meyer Dik published a

Yiddish version of Uncle Tom's Cabin

(Di shklaferay, oder

Di Laybegenshaft, 1887) to air the issues of

slavery and freedom, incidentally Judaizing the story

(Uncle Tom and his emancipated family convert and join the Jewish

people!)" [p. 33]

On the title

page of Dik's work we read a typical promotional

passage: "This is a frightening and wonderful true story that happened in

America a little over forty years ago and that involved a certain Negro (Moor)

"Uncle Tom" who was the slave of a certain Jewish planter (estate

owner) Abraham Shelby. This story is written in English and has been translated

in all languages. Now we have a Yiddish translation with a fine 'Introduction'

by A.M.D . …Vilna, 1887.

A cover of a 1911 translation of Uncle Tom's

Cabin by Y. Yofe is given below.

9) ---------------------------------------------------

Date:

25 July 2008

From: Yidishe heftn

Subject: Periodicals Received: Yidishe heftn no.

127/8 [July/August 2008]. Issue theme:

10) ---------------------------------------------------

Date:

25 July 2008

From: Eleanor Mlotek

Subject: Cover of songbook, Mir trogn a gezang [includes Gebirtig's "Motele"]

11)

---------------------------------------------------

Date:

25 July 2008

From: Eleanor Mlotek

Subject: "Motele”

lyrics and score

12)

---------------------------------------------------

Date:

25 July 2008

From: ed.

Subject: "Motele"

sung by Menakhem Bernshteyn

"Motele" sung by Menakhem Bernshteyn

Artist: Menakhem Bernshteyn [Menachem Bernstein] (Please see next section for Portrait,

Biographical Sketch)

Accompanist: Haggai Spokoiny

Recording Technician: Tal Daniel

13)

---------------------------------------------------

Date:

25 July 2008

From: ed.

Subject: Portrait and biographical sketch

of Menakhem Bernshteyn [Menachem Bernstein], Haifa-based folksinger and reciter.

|

|

Menakhem Bernstein was born in |

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

End of The Mendele Review Issue

12.014

Editor, Leonard Prager

Editorial Associate, Robert Goldenberg

Subscribers to Mendele (see

below) automatically receive The Mendele Review.

You may subscribe to Mendele, or,

kholile, unsubscribe, by visiting the Mendele

Mailing List

**** Getting back issues ****

The Mendele

Review

archives can be reached at: http://yiddish.haifa.ac.il/tmr/tmr.htm

Yiddish Theatre Forum archives can be

reached at: http://yiddish.haifa.ac.il/tmr/ytf/ytf.htm

Mendele on the web: http://shakti.trincoll.edu/~mendele/index.utf-8.htm

***