The Mendele

Review: Yiddish Literature and Language

(A Companion to MENDELE)

---------------------------------------------------------

Contents of Vol.

11.010 [Sequential No. 187]

Date:

"There are some who consider its early disappearance by no means a

certainty." [Helena Frank in 1906]

1) This issue of TMR (ed).

2) Helena

Frank's 1906 Y.-L. Perets Volume

3) Leo Wiener's Predictions, 1899

4) Mendl Man's Historic Volume of Verse, Communist

5) New Volume of Poems by Boris Karloff,

2007 (ed.)

6) The Incredible Rose Bilbool (ed.)

1)---------------------------------------------------

Date:

From: ed.

Subject: This

issue of TMR

* Yiddish has often been the victim of wobbly predictions. In

1906 Helena Frank, the first translator of Yiddish into English, saw the

possibility of a flourishing Yiddish culture in a "Free Russia" where

in her day the great mass of Jews were Yiddish-speakers. For a brief period

Yiddish did flourish in the

2)----------------------------------------------------

Date:

From: ed.

Subject: Helena Frank's 1906 Perets Volume, reprinted

1936

In the "Preface" to her Perets

translations, Helena Frank recomments Leo Wiener as a

source of information on Perets. Unlike the author of

our first systematic history of Yiddish literature, she is hesitant in

predicting the demise of Yiddish: "The future of Yiddish in a Free Russia

is hard to tell. There are some who consider its early disappearance by no

means a certainty." She cites Perets' metaphoric

appeal for Jews to cultivate their own soil, words that express a widespread

cultural nationalism but not Zionism. Mendl Mann in

an historic volume of verse discussed below employs the same equally ambiguous

agricultural imagery. Frank's projection of a "Free Russia" -- in

which she was far from alone in 1906 -- proved to be one of the most tragic

illusions of all times.

3)----------------------------------------------------`

Date:

From: ed.

Subject: Leo Wiener's Predictions

In The History of Yiddish Literature in the Nineteenth Century (London:

John C. Nimmo, 1899), Harvard professor Leo Wiener

wrote in his "Preface": The purpose of this work will be attained if

it throws some light on the mental attitude of a people whose literature is

less known in the world than that of the Gypsy, the Malay, or the North

American Indian." [p. xi] In his

"Introduction" he wrote: It is hard to foretell the future of Judeo-German.

In

Wiener's speculations invite the following comments:

1.) There is today an extensive literature – texts, criticism, multi-media – on Yiddish literature, language and culture.

2.) Yiddish is taught in many universities the world over. 3.) Yiddish

is now a universally accepted name and Judeo-German is no longer used

(except by a few specialists who are uncomfortable with Western Yiddish.

4.) Yiddish has been in decline but there are still many speakers. In any

event, "extinction" does not appear imminent. 5.) Mass influx of

immigrants to

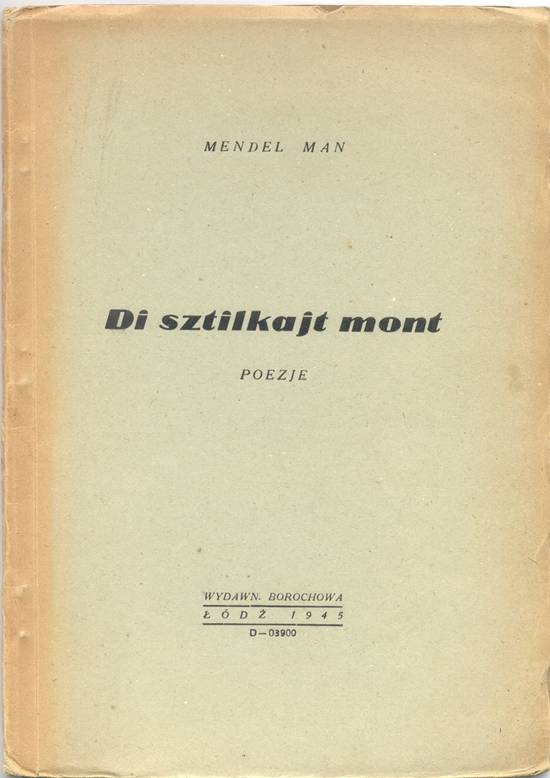

4)-----------------------------------------------------

Date:

From: ed.

Subject: Mendl Man's Historic Volume of Verse,

Communist

In Mendl Man's Di shtilkeyt mont; lider un baladn (The Quiet Demands its Due; Poems and Ballads), Lodz: Borokhov Farlag, 1945 [aroysgegebn bay der mithelf fun ts(entral) k(omitet)

fun der yidisher arbeter-partey "poyl-tsien"

in Poyln], Nakhmen Blumental (1905-1983), the Holocaust researcher, writes in

the "Foreword" (p.4): "Di shtilkeyt mont iz dos ershte yidishe bukh, vos dershaynt

in nay-oyfgeshtanenen Poyln.

Vi shver s'zol

nisht zayn dos itstike lebn oyf

di khurves fun poylishn yidntum, muzn mir ober

shtrebn oyftsushteln umatum dos, vos iz tseshtert gevorn.

Farheyln di vunden. Deriber batrakhtn mir dos dershaynen fun dem bukh yidishe

lider vi an onheyb fun der banayung fun dem yidishn literarishn shafn in poyln." [The

Quiet Demands Its Due is the first Yiddish book to appear in

newly-restored

מענדל מאַן

מײַן תּפֿילה

אָ גאָט! װאָס האָסט מײַן פֿאָלק אױסדערװײלט צום

רום,

כּדי דער פֿײַנט זאָל אונדז אױסװײלן צום אומקום.

האָסט אונדז געגעבן קלאָרע און ליכטיקע אױגן,

כּדי פֿינסטערניש זאָל אײביק אױף זײ לױערן.

מיר האָבן אין דײַן נאָמען ליבע צו מענטשן

געטראָגן

און געװען – דער אָנזאָג פֿון העלן מאָרגן,

און ס'האָט דאָס סאַמע שװאַרצטע פֿון דער נאַכט

דאָס פֿאָלק – דײַן אױסדערװײלטס אומגעבראַכט.

ס'ברענט די שׂינאה – צו די אײנצל-געבליבינע פֿון

מײַן פֿאָלק,

װי אַ ניט פֿאַרלאָשענער שײַטער.

אָ, גאָט! הער מײַן קול.

איך װיל מער ניט זײַן דער אױסדערװײלטער!

אָ גאָט! אױב ביסט דאָ,

גיב מיר פֿון יעדן פּשוטן פּױער די רו,

װאָס אַקערט דורות

די זעלבע ערד פֿון אורזײדעס.

בענטש מײַנע הענט צו שװערסטע מי,

אױף מײַן אײגענעם פּלײן,

פֿון זײַן מיט זיך און דיר אַלײן,

אַז ס'זאָל מײַן שפּאַן ניט אָפּשטײן

פֿון אַלעמענס טריט,

אַז ס'זאָל ניט אומעטיקער קלינגען מײַן ליד.

אָ, גאָט!

פֿאַרלעש די שׂינאה – דעם נאָך ניט דערברענטן

פֿלאַם!

נעם אַראָפּ מיר די לאַסט פֿון אַן אױסדערװײלטן

שטאַם!

אױב ביסט דאָ,

אוּן מײַן תּפֿילה דו הערסט,

גיב מיר פֿון יעדן פּשוטן פּױער די רו,

וואָס אַקערט זײַן אײגענע ערד.

(ז' 38)

--------------------------

mayn

tfile

o got! vos host mayn folk oysderveylt tsum rum,

kedey

der faynt zol undz oysveyln

tsum umkum.

host undz gegebn klore un likhtike oygn,

kedey

finsternish zol eybkik oyf zey

loyern.

mir hobn in dayn nomen libe tsu mentshn getrogn

un geven – der onzog fun heln morgn,

un s'hot dos same shvartste fun der nakht

dos folk – dayn oysderveylts umgebrakht.

s'brent di sine – tsu di eyntsl-geblibine fun mayn folk,

vi a nit farloshener shayter.

o, got! her

mayn kol.

ikh vil mer nit zayn der oysderveylter!

o got! oyb bist do,

gib mir fun yedn poshetn poyer di ru,

vos akert doyres

di zelbe erd fun urzeydes.

bentsh mayne hent tsu shverste mi,

oyf mayn eygenem pleyn,

fun zayn mit zikh un dir aleyn,

az s'zol mayn shpan nit opshteyn

fun alemens trit,

az s'zol nit umetiker klingen mayn lid.

o, got!

farlesh di sine – dem nokh nit derbrentn flam!

nem

arop mir di last fun an oysderveyltn shtam!

oyb

bist do,

un mayn tfile du herst,

gib mir fun yedn poshetn poyer di ru,

vos akert zayn eygene erd.

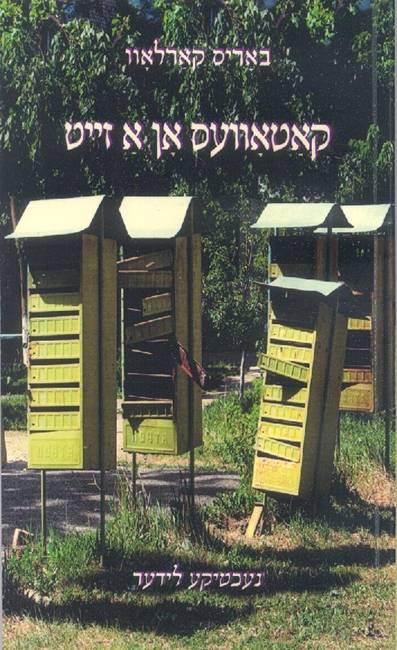

5)-----------------------------------------------------

Date:

From: ed.

Subject: New Volume of Poems by Boris Karloff (ed.)

Boris Karloff. Katoves on a zayt. Nekhtike lider

1993-2001. [I

kid you not! Poems of Yesteryears]. Jerusalem: Farlag "Eygns", 2007.

Foreword by H. Binyamin. Photo on front

cover by Artur Fratczak (Tulchin, May 2007), 62 pages.

ISBN-978-965-7188-45-3.

In "A tfile" ('A

Prayer') the father asks for protection from the "mayler"

('mouths') that often embitter the life of talents greater than theirs. "Bashirem mir," he

pleads, "Protect me." In "Shir

ha shirem" ('Song of the Umbrella'

), the son plays on the biblical name of "The Song of Songs" –

Shir haShirim,

relaxedly turning a song into an umbrella, an

instance of his verbal playfulness. Against unsympathetic academic voices he

musters his irony, the katoves of the title

and his poetic wit. We see this in "In flug":

"Ikh un professor shmeruk,/Mir kenen zikh,

dakht zikh, shoyn yorn, --" and "Di zibn heldn":

"In undzer sheyner un farshemter dire/Hobn zikh pasyelet zibn

voyle ire…" Karloff's

ear for dialecticisms joins his filial piety in the moving "Itset. In "Far fri,"

the poet leaves the petty world behind and, with the control often seen in the

verse of Kerler senior, pens a fine lyrical

meditation.

Karloff feels free to

soak up clichés from many sources and readers will respond differently

to this quirk. A native English speaker inevitably hears the poet's "Kh'ob mayn harts forlorn in Khlandidno" ('I lost my heart in Llandudno

Junction') as a worn-out phrase and will free-associate to the many popular

songs beginning with the line "I lost my heart in..." In defence of this practice one can argue that Karloff consciously makes his verse contemporary and will Yiddishize English words and names as he sees fit – e.g. Dzhankshon ('Junction').

This issue began on the theme of "wobbly predictions"

for the future of Yiddish. The kind of vitality Yiddish poetry calls for in

2007 is not forthcoming in large servings, but Karloff's

latest slim volume makes one almost optimistic.

Father: Yoysef Kerler's "A tfile"

יוסף

קערלער

אַ

תפֿילה

רבונו של עולם, דײַן גנאָד

און דײַן חסד!

צי

בין איך דאָס װערט און צי קאָן איך פֿאַרגעסן׃

צעפֿליקט, מיט

דײַן הילף, כ'האָב די קנעכטישע פּענט,

בשלום

אַרױס פֿון גזלנישע הענט,

אַ הײם

האָסט געבראַכט מיר מיט קינד

און מיט װײַב

און

ברױט כ'האָב צו זעט און אַ מלבוש צום לײַב,

נאָר טאַטעניו־פֿאָטער,

מײַן ליכטיקער האַר,

היט אױס מיך אַצינד פֿון אַ נײַער געפֿאַר׃

בײַ קײנעם

ניט מאַך אין די אױגן מיר גרױס,

פֿאַרפּאַנצער מײַן האַרץ קעגן קלײנלעכע פֿײַלן

–

פֿון

גױישע הענט כ'בין בשלום אַרױס,

באַשיץ און באַשירעם פֿון ייִדישע מײַלער!

[אַלמאַנאַך ייִדישע שרײַבער פֿון ירושלים, 1973, ע'

63.]

[כלל-שפּראַך׃ פּענטעס]

Son: Boris Karloff's "Far fri"

פֿאַר פֿרי

קום

שפּעט בײַ נאַכט פֿון שטוב אַרױס

װען קײנער קערט

ניט הערן

און

קוק זיך צו װי אײַן און אױס

עס זשומען

קלאָר די שטערן.

און

װען דערזען דו װעסט דעם זשום,

װעסטו פֿאַר זיך געפֿינען

דעם שאַ־און־שטיל

פֿון שטערן־שפּיל,

פֿון

אײביקן נגינה.

און

װען דער קלאָרער

שטערן־טרעל

װעט

טרײסטן דיך ביז טרערן,

װעסט דאַן דײַן האַרץ

װי

ס'האַרץ פֿון װעלט

דערשפּירן און דערהערן.

קום

שפּעט בײַ נאַכט פֿון זיך אַרױס

װען קײנער קערט

ניט שטערן

און

האָרך זיך אײַן –

װעלט אײַן,

װעלט אױס –

אין

זשום פֿון זײַן און װערן.

Note:

I have taken the liberty to diverge

from the authors' spelling in a few particulars (indicated by red-coloring), as

required by the Takones fun yivo .

Thus I give bay nakht and far fri as separate words. I

distinguish tsvey yudn

(ey) from pasekh tsvey yudn (ay). It is

important to be able to see the difference between leyb

(lion) and layb (body), between eyn and ayn. Native

speakers do not require the Takones to

understand and read Yiddish aloud, but even for them a single widely accepted

rational spelling system is a desideratum.

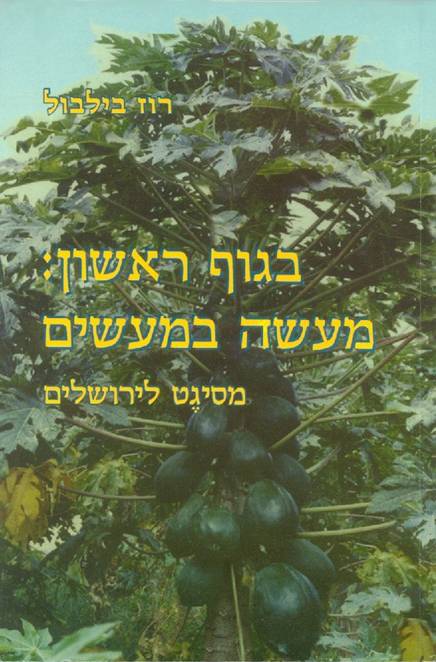

6)-----------------------------------------------------------

Date:

From: ed.

Subject: The Incredible Rose Bilbool (ed.)

Roz Bilbool. Be-guf rishon: ma'ase be-ma'asim. mi-siget

le-yerushalayim, בעריכת

רותי זקוביץ

[Rose Bilbool. Personally Speaking: Deeds Recounted

from Siget to

I know of no

one in the world of Yiddish studies who is more deeply involved in extensive,

time-consuming research projects than Hebrew University Professor of Yiddish Yechiel Szeintuch, keen student

of the writings of Yoysef Tunkl

(Der tunkeler), Ka-Tsetnik, Yitskhok Katsenelson Yeshayohu Shpigl, Arn Tseytlin,

Yankev Fridman, Mortkhe Shtrigler and others. Yet

this scholar, together with a small band of diligent helpers, spent months and

months interviewing an elderly woman whose métier was in no way

connected with Yiddish, but -- exotic though this may sound – with

the papaya plant, of whose multiple medicinal and cosmetic applications she may

justly claim to be the world leader. Interviewing Rose Bilbool,

whose very name excites speculation, was a self-powering experience for the

interviewer who framed the questions and taped the replies (in Hebrew), the

transcriber of over a year's accumulation of tapes, the ground editor of the

bulk work who brought it into orderly shape and, finally, the style editor who

swept away inconsistencies. In her mid-nineties while this adventure in

autobiography proceeded, it developed into a gripping personal history, which

is also a mirror of the larger events in which it has been enacted.

Rose Bilbool, as a quick internet check via Google will

show, is no obscure personage. Much is known of her papaya work in

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

End of The

Mendele Review Vol. 11.010

Editor, Leonard

Prager

Subscribers to Mendele

(see below) automatically receive The Mendele

Review.

Send "to subscribe" or

change-of-status messages to: listproc@lists.yale.edu

a. For a temporary stop: set mendele mail postpone

b. To resume delivery: set mendele mail ack

c. To subscribe: sub mendele first_name last_name

d. To unsubscribe kholile: unsub

mendele

*** Getting back issues ***

The Mendele

Review archives can be

reached at: http://yiddish.haifa.ac.il/tmr/tmr.htm

Yiddish Theatre Forum archives can be reached at: http://yiddish.haifa.ac.il/tmr/ytf/ytf.htm

Mendele on the web: http://shakti.trincoll.edu/~mendele/index.utf-8.htm

***