The Mendele Review:

Yiddish Literature and Language

(A Companion to MENDELE)

---------------------------------------------------------

Contents of Vol. 10.005 [Sequential No. 170]

Date:

1) This issue (ed.)

2) Review of Jerold Frakes' Early Yiddish Texts (Marion Aptroot)

3) "Die fragen [di frages], vos men shtelt baym veren [vern] a sitizen

[birger]" (Robert Goldenberg)

4) Books Received (ed.)

a) Shalom Luria, Vilna Shelanu-Ir VaEm

b) Mordkhe Schaechter, Di geviksn velt in yidish

Click here to enter: http://yiddish.haifa.ac.il/tmr/tmr10/tmr10005.htm

1)---------------------------------------------------

Date:

From: ed.

Subject: This issue

***The discipline of Yiddish studies has been

growing apace, building on the basis of work carried through by earlier

generations of scholars. One area that has made great advances is that of Old

Yiddish, which now boasts a number of critical editions of key works and,

for the first time a comprehensive textbook that surveys the entire field.

Jerrold Frakes's Early Yiddish Texts is here reviewed by Professor

Marion Aptroot of the Lehrstuhl fuer jiddische Kultur, Sprache un

Kultur, Heinrich-Heine Universitaet, Duesseldorf.

***The recent fracas over a Spanish translation of

the "Star-Spangled Banner" brought into momentary prominence earlier

parallel translations in other languages, including Yiddish. The latter point up the role of Yiddish as a

handmaiden in the acculturation of Yiddish-speaking immigrants. As early as

1896 the lexicographer, journalist and author Aleksander Harkavi

(1863-1939) in one of the many periodicals he founded and wrote for, was

publishing help columns for prospective naturalization applicants. In

the pages brought here in both Yiddish and Latin letters, we see how

an effort is made to write English in Yiddish letters. This suggests that many

Jewish immigrants mastered a rudimentary English before they could match

English alphabet to English sounds. Nayer leksikon fun der yidisher

literatur (vol. 3:82) records the shortlived

2)--------------------------------------------

Date:

From: Marion Aptroot

Subject: Review of Jerold Frakes' Early Yiddish Texts

Early Yiddish Texts 1100–1750.

Edited by Jerold C. Frakes.

Jerold Frakes’s copious anthology, Early

Yiddish Texts 1100–1750, with its 889 pages of texts and excerpts

accompanied by succinct introductions and selected bibliographical information

provides a weighty argument in discussions with those who think Yiddish only

became a written language in the nineteenth century. Even among those who are

aware that Yiddish texts from earlier centuries have come down to us, the

cliché often rules that virtually all older Yiddish texts – apart

from some medieval epics and Elye Bokher’s Renaissance romances – were intended

for pious women. This anthology reflects the scholarship of the past two

centuries that has described and studied a highly diverse body of Yiddish texts:

Frakes includes Bible translations, Biblical or Midrashic as well as secular

epics, fables, letters, minhogim (customs), glosses and glossaries, vikuekh-lider

(poetic disputations), drama, ethical and moral literature, satire and humour,

historical songs and historiography, legal and para-legal texts, responsa,

liturgical texts, a newspaper, songs, medical and magical texts, paratexts,

prose narratives (mayses), and travel guides.

With this book, guided by chronological and genre

indices, one can embark on a tour of discovery. The indices facilitate access

to the anthology, but in some cases one can dispute the date or the genre under

which a text is classified. The latter is nearly always a moot point in

literary histories and anthologies, but a division into genres is a practical

organizing principle. Still, it is surprising to find Isaac Wetzlar’s Libes

briv not only under the heading of muser but also that of Kabbalah.

Kabbalah is currently a live topic and the scholarly debate on the nature and

extent of the transmission of kabbalistic narratives and ideas in early Yiddish

texts is ongoing. This connection, however, is puzzling to this reviewer, who

divines a mishap during the production process: Frakes’s introduction to the

excerpt provides no arguments for this classification.

Whereas most users will be aware that ideas about

the classification of texts according to genre are in constant flux and that

what is understood by these labels changes through the ages, they will probably

accept the date of texts as a given. The texts should be dated with extreme

care, taking account of codicological, linguistic and stylistic criteria.

Frakes, overall, is careful and dates the texts on the basis of colophons or

title pages of manuscripts and printed texts and is not afraid of giving vague

indications where there is uncertainty. Unfortunately,

this caution is not always upheld. The heading of text Nr. 14, “Vu zol ikh hin”

/ ‘Whither Shall I Go?’, for example, states that it was written in the

fourteenth century. The dating of the text, however, is not at all certain. The

manuscript in which it is found dates from the fourteenth century. The poem in

question, according to Frakes, “is written in an Ashkenazic cursive hand

distinct from the formal book hand of the main text” (p. 64). Frakes bases his

dating on the fact that “[t]he hand of the poem is characteristic of the

earliest period in Old Yiddish texts and may well be a near contemporary of the

main text.” I am sure that Jerold Frakes has read many Yiddish manuscripts and

that he has developed an eye for paleographic differences, but the paleography

of Ashkenazic writing alone does not allow precise dating. The language in

which the poem is written is strikingly more modern than that of the texts

preceding and following it in this anthology. The spelling conventions to which

the scribe adheres, too, are more typical of sixteenth-century works.

For this anthology Jerold Frakes has consulted many

original manuscripts and printed works as well as critical editions. The main

objective of this anthology is “to provide reliable texts of a representative

range of works from early Yiddish” (p. lxxi). In this Frakes has succeeded

since the number of errors in the Old Yiddish texts appears to be extremely

low. However, one would sometimes wish for more editorial information when he

provides different scholars’ (and his own) textual readings of originals that

are sometimes hard to decipher or contain typographical errors. As he states in

the introduction: “A text edition may be provided with various types of notes,

such as explanatory notes (that identify references and allusions to or

citations of other texts, such as Bible, Talmud, or midrash, or identify

people, places or events mentioned in the text), lexical notes that explain

‘difficult’ words, and textual readings by previous scholars” (p. lxxi). These

were not provided because of other priorities and considerations of space, but

those who try to read these texts may give up because of the difficulties they

provide. If one is not a polyglot like Frakes and familiar with a number of

European languages from the Middle Ages and Early Modern Period, one may become

frustrated by the lack of explanatory notes.

The attention devoted to checking the early Yiddish

texts was not paid to the bibliographies.

This criticism aside, Jerold Frakes’ anthology

fulfills the aim of providing reliable texts for advanced students. One hopes

that this book will contribute to Old and Middle Yiddish texts becoming part of

the curriculum at more universities. Time will tell if this book will indeed be

used for the academic teaching of Early Yiddish literature. At universities

where Old and Middle Yiddish literature and language are taught, teachers

attach much value to their students becoming familiar with the look of older

Yiddish manuscripts and printed books and it is unlikely that they will use

this edition for texts which – for lack of explanatory notes – are just as easy

or difficult to read in the original if reproductions are available. Students

who can read Yiddish in square characters can usually master the Ashkenazic

semi-cursive and cursive scripts without much difficulty. In my experience in

teaching early Yiddish texts, students prefer facsimiles once they become

familiar with the writing. Furthermore, a considerable number of Yiddish

printed books of the 16th to mid-18th century can easily be found online [3]or as part of microfiche collections.[4]

Where early Yiddish texts are taught in facsimile, this impressive compilation

can still be used as an accompanying manual providing materials (textual

readings by scholars – where available –, short introduction and

bibliographical references for further reading) which can be both an aid to and

the object of further discussions in the study of pre- and early modern Yiddish

texts.

This anthology also makes evident the need for good

scholarly editions of early Yiddish texts which include “various types of

notes, such as explanatory notes (that identify references and allusions to or

citations of other texts, such as Bible, Talmud, or midrash, or identify

people, places or events mentioned in the text), lexical notes that explain

‘difficult’ words, and textual readings by previous scholars” (to quote Jerold

Frakes, p. lxxi, out of context). A number of editions that provide these aids

have appeared and such works continue to appear, most recently Chava

Turniansky’s prize-winning Glikl edition.[5]

With this compilation of a wide choice of works and

excerpts, Jerold Frakes has provided the only single-volume companion for

exploring early Yiddish literary and non-literary texts in independent studies.

This pioneering work will doubtless help raise interest in Medieval and Early

Modern Yiddish.

[1] Erika Timm, Zur Frühgeschichte der jiddischen

Erzählprosa: Eine neuaufgefundene Maise-Handschrift. In: Beiträge

zur Geschichte der deutschen Sprache und Literatur 117,2 (1995), p.

243-280. Far from simply being a description of a newly

discovered mayse-codex, this is also one of the best introductions to

the Mayse-bukh and full of new information.

The articles of Lucia Raspe on specific Ashkenazic

prose narratives which feature, among other sources, in the Mayse-bukh

and Mayse nisim are among the most innovative studies relevant to the

study of older Yiddish texts. It would have been very helpful to students and

teachers of Early Yiddish literature if their attention had been drawn to them,

e.g. Emmeram von Regensburg, Amram von Mainz: Ein christlicher Heiliger in der

jüdischen Überlieferung, in: Neuer Anbruch. Zur deutsch-jüdischen Geschichte und Kultur, Michael Brocke, Aubrey Pomerance and Andrea

Schatz, eds., Berlin: Metropol, 2001, p. 221–241.

[2] Michael Stanislavski, The Yiddish “Shevet

Yehudah”: a study in the “Ashkenization” of a Spanish-Jewish classic. In: Jewish

History and Jewish Memory; Essays in Honor of Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi. Ed.

by Elisheva Carlebach, John M. Efron, David N. Myers.

[3] Scans of Yiddish works from the extensive holdings

of the University Library of Frankfurt on the

[4] E.g., the collection of Old Yiddish Literature

edited by Chone Shmeruk, based mainly on the Yiddish collection of the Bodleian

Library in Oxford (Leiden: IDC-Microfilms) or the Yiddish books from the

Thyssen Collection, Rostock, and parts of the Wagenseil collection, both edited

by Heike Tröger and Hermann Süss (Erlangen: Harald Fischer Verlag). A

notable recent facsimile edition with translation and commentary is Astrid

Starck’s edition of the Mayse Bukh: Un beau livre d’histoires / Eyn

shön Mayse bukh: facsimilé de l’edition princeps de Bâle

(1602).

[5] Chava Turniansky, ed., Glikl – zikhronot

1691–1719,

3)------------------------------------------------------------

Date:

From: Robert Goldenberg

Subject: Die fragen [Di frages], vos men shtelt baym veren [vern] a sitizen

[birger]

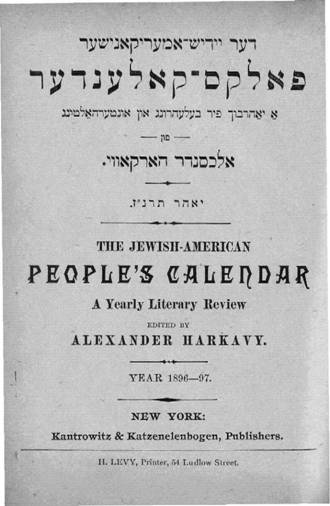

Cover of Der yidish-amerikanisher folks-kalendar, 1896-1897

Click here for higher resolution

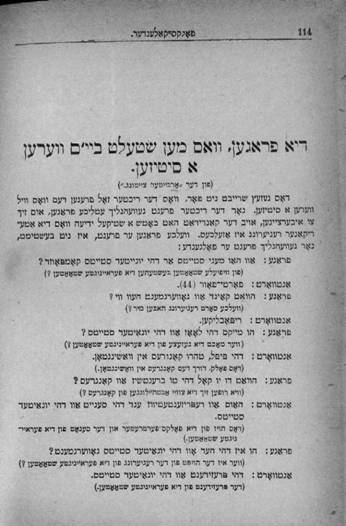

"Die fragen [di frages], vos

men shtelt baym veren [vern] a sitizen [birger]", p.114

Click here for higher resolution

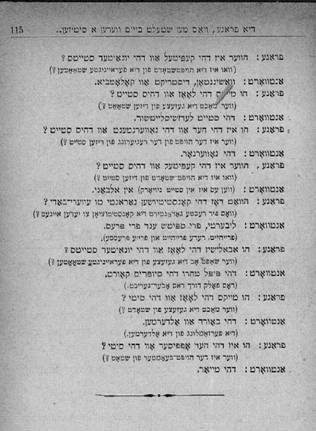

"Die fragen [di frages], vos men shtelt baym veren [vern] a sitizen

[birger]", p.115

Click here for higher resolution

Die fragen [Di frages], vos men shtelt baym veren [vern] a sitizen

[birger]

(fun der Arbayter [Arbeter]

Tsaytung)

Dos gezets shraybt nit for, vos der rikhter zol fregen dem vos vil veren [vern]

a sitizen [birger]. Nor der rikhter fregt gevehnlikh [geveynlekh] etlikhe

[etlekhe] fragen [frages], um zikh tsu ibertsaygen, oyb der kandidat hot khotsh

a shtikel [shtikl] yedie vos di amerikaner regirung iz azelkhes. Velkhe

fragen [frages] fregt, iz nit beshtimt [bashtimt], nor gevehnlikh [geveynlekh]

fregt er folgende:

frage:

àÇÔ äàÇå îòðé ñèÖèñ àÇø ãäé éåðééèòã

ñèééèñ ÷àÈîôÌàÈåæã?

Of how many states are the

antvort [entfer]:

ôÏàÈøèéÎôÏàÈåø

Forty-four (44).

frage:

äååàÇè

÷ÖÇðã àÇåå âàÈÔòøðîòðè äòÔ Ôé?

What kind of government have we? (Velkhe sort regirung hoben [hobn] mir?)

antvort [entfer]:

øéôÌåáìé÷òï

Republikan.

[Ed:. Note how, as in the above, Yiddish letters are used to write

English words throughout the citizen's catechism.]

frage: Who makes the laws of the

antvort [entfer]: The People, through Congress in

frage: What do you call the two

branches of Congress? (Vi rufen [rufn] zikh di tsvey abtheylungen [opteylungen]

fun kongres?)

antvort [entfer]: House of

Representatives and the Senate of the

frage: Who is the head of the

antvort [entfer]: The President of the

frage: Where is the capitol of the

antvort [entfer]:

frage: Who makes the laws of this

state? (Ver makht die gezetse [di

gezetsn] fun dizen shtaat [dizn shtaat]?)

antvort [entfer]: The State Legislature.

frage: Who is the head of the

government of this state? (Ver iz der

hoypt fun der regierung [regirung] fun dizen steyt [dizn shtat]?)

antvort [entfer]: The Governor.

frage: Where is the capital of this

state?

antvort

[entfer]: (Ven es iz in steyt [shtat]

Nyu york) In Albany.

frage: What does the Constitution

guarantee to everybody? (Vos fir rekhte [Vosere rekht] garantirt die konstitutsiyon

[di konstitutsye] tsu yeden [yedn] eynem?)

antvort [entfer]:

frage: Who abolishes the laws of the

antvort entfer]: The People through the Supreme

Court. (Dos folk durkh dos ober-gerikht [dos Hekhste gerikht])

frage: Who makes the laws of the

city? (Ver makht die gezetse [di

gezetsn] fun shtodt [shtot]?)

antvort [entfer]: The Board of Aldermen. (Die

ferzamlung fun di oldermen [di Kolegye fun shtot-yoyetsim].)

frage: Who is the head officer of the

city? (Ver iz der hoypt-beamter

[baamter] fun shtot?)

antvort [entfer]: The Mayor.

4)-------------------------------------------------

Date:

From: ed.

Subject: Books Received

a) Shalom Luria, Vilna Shelanu-Ir VaEm

Shalom Luria. Vilna Shelanu -- Ir VaEm. [Tadpis mitokh seyfer

hazikaron leken "HaShomer HaTsair" beVilna: Lahavot 'HaShomer

HaTsair', Tel-Aviv, 1993; reprinted from Shalom Luria. "Vilna

Shelanu - Ir VaEm," Madurot; HaShomer HaTsair beVilna veHaGalil, Givat

Khaviva: Yotsey haShomer haTsair beVilna veHaGalil veYad Yaari, 1991,

pp. 20-71].

Shalom Luria, the son of the distinguished Yiddish linguist Zelik Kalmanovitsh (1885-1944) and an accomplished Yiddish scholar and translator in his own right, movingly describes his beloved Vilna, which he left as a young man to "go up to" the Land of Israel -- with the blessings of his parents whom he was never to see again. These beloved parents "brought him to Vilna when he was a child, raised and educated him and planted in him a love for the Jewish people and its two tongues -- Yiddish and Hebrew ...." In 22 succinct chapters, this brochure of 100 pages (with a 4-page bibliography) sketches in an individual manner the cultural biography of Jewish Vilna through the ages, a remarkable story.

b) Mordkhe Schaechter, Di geviksn-velt in yidish

Mordkhe Schaechter. Di geviksn-velt in yidish

[English title: Plant Names in Yiddish] (

----------------------------------------

End of The Mendele Review Vol. 10.005

Editor, Leonard Prager

Subscribers to Mendele (see below) automatically receive The Mendele Review.

Send "to subscribe" or change-of-status messages to: listproc@lists.yale.edu

a.

For a temporary stop: set mendele mail postpone

b. To resume delivery: set mendele

mail ack

c. To subscribe: sub mendele

first_name last_name

d. To unsubscribe kholile: unsub

mendele

****Getting back issues****

The Mendele Review archives can be reached at: http://yiddish.haifa.ac.il/tmr/tmr.htm

Yiddish Theatre Forum archives can be reached at: http://yiddish.haifa.ac.il/tmr/ytf/ytf.htm

***